「イナンナ」の版間の差分

(→私的解説) |

|||

| (同じ利用者による、間の556版が非表示) | |||

| 1行目: | 1行目: | ||

[[File:Seal of Inanna, 2350-2150 BCE.jpeg|thumb|500px|両手に鎚矛を持ち、背中に翼の生えた天の女主人・イナンナ。<br />イナンナがライオンの背に足をかけ、その前にニンシュブルが立って敬意を表している様子を描いた古代アッカド語の円筒印章(紀元前2334年頃~2154年頃)<ref>Wolkstein, Kramer, 1983, pages92, 193</ref>]] | [[File:Seal of Inanna, 2350-2150 BCE.jpeg|thumb|500px|両手に鎚矛を持ち、背中に翼の生えた天の女主人・イナンナ。<br />イナンナがライオンの背に足をかけ、その前にニンシュブルが立って敬意を表している様子を描いた古代アッカド語の円筒印章(紀元前2334年頃~2154年頃)<ref>Wolkstein, Kramer, 1983, pages92, 193</ref>]] | ||

[[ファイル:Ishtar vase Louvre AO17000-detail.jpeg|thumb|right|250px|花瓶に描かれたイナンナ]] | [[ファイル:Ishtar vase Louvre AO17000-detail.jpeg|thumb|right|250px|花瓶に描かれたイナンナ]] | ||

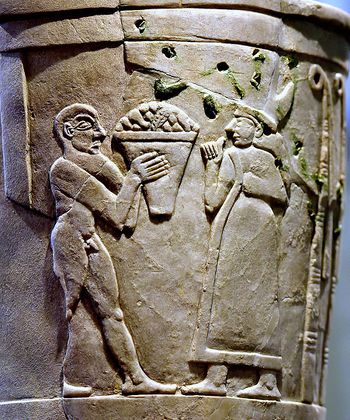

| + | [[File:Inanna receiving offerings on the Uruk Vase, circa 3200-3000 BCE.jpeg|thumb|350px|供物を受け取るイナンナ(ウルクの大杯)(前3200-前3000年頃)]] | ||

'''イナンナ'''(シュメール語:𒀭𒈹、翻字] <sup>D</sup>INANNA、音声転写: Inanna)は、シュメール神話における[[金星]]、愛や美、戦い、豊穣の女神。別名[[イシュタル]]。ウルク文化期(紀元前4000年-紀元前3100年)からウルクの守護神として崇拝されていたことが知られている([[エアンナ]]に祀られていた)。シンボルは[[藁|藁束]]と[[八芒星]](もしくは十六芒星)。聖樹は[[アカシア]]、聖花は[[ギンバイカ]]、聖獣は[[ライオン]]。 | '''イナンナ'''(シュメール語:𒀭𒈹、翻字] <sup>D</sup>INANNA、音声転写: Inanna)は、シュメール神話における[[金星]]、愛や美、戦い、豊穣の女神。別名[[イシュタル]]。ウルク文化期(紀元前4000年-紀元前3100年)からウルクの守護神として崇拝されていたことが知られている([[エアンナ]]に祀られていた)。シンボルは[[藁|藁束]]と[[八芒星]](もしくは十六芒星)。聖樹は[[アカシア]]、聖花は[[ギンバイカ]]、聖獣は[[ライオン]]。 | ||

イナンナ(ɪˈnɑːnə; 𒀭𒈹、<sup>D</sup>inanna, also 𒀭𒊩𒌆𒀭𒈾 <sup>D</sup>nin-an-na<ref>Heffron, 2016</ref>)<ref>Sumerian dictionary, http://oracc.iaas.upenn.edu/epsd2/cbd/sux/N.html , oracc.iaas.upenn.edu</ref>は古代メソポタミアの愛と戦争と豊穣の女神である。また、美、性、神の正義、政治的権力とも関連している。シュメールでは「イナンナ」の名で、後にアッカド人、バビロニア人、アッシリア人によって「イシュタル('''Ishtar'''、ˈɪʃtɑːr; 𒀭𒀹𒁯、<sup>D</sup>ištar<ref>Heffron, 2016</ref> occasionally represented by the logogram 𒌋𒁯)」の名で崇拝された。イナンナは「天の女王」と呼ばれ、ウルクの町にある[[エアンナ]]神殿が彼女の主要な信仰の場であり、守護神であった。金星と結びついた彼女は、象徴としてライオンや八芒星などが有名である。彼女の夫はドゥムジ神(後のタンムーズ神)であり、彼女の侍女は女神ニンシュブル(後に男神イラブレットやパプスカルと混同される)であった。 | イナンナ(ɪˈnɑːnə; 𒀭𒈹、<sup>D</sup>inanna, also 𒀭𒊩𒌆𒀭𒈾 <sup>D</sup>nin-an-na<ref>Heffron, 2016</ref>)<ref>Sumerian dictionary, http://oracc.iaas.upenn.edu/epsd2/cbd/sux/N.html , oracc.iaas.upenn.edu</ref>は古代メソポタミアの愛と戦争と豊穣の女神である。また、美、性、神の正義、政治的権力とも関連している。シュメールでは「イナンナ」の名で、後にアッカド人、バビロニア人、アッシリア人によって「イシュタル('''Ishtar'''、ˈɪʃtɑːr; 𒀭𒀹𒁯、<sup>D</sup>ištar<ref>Heffron, 2016</ref> occasionally represented by the logogram 𒌋𒁯)」の名で崇拝された。イナンナは「天の女王」と呼ばれ、ウルクの町にある[[エアンナ]]神殿が彼女の主要な信仰の場であり、守護神であった。金星と結びついた彼女は、象徴としてライオンや八芒星などが有名である。彼女の夫はドゥムジ神(後のタンムーズ神)であり、彼女の侍女は女神ニンシュブル(後に男神イラブレットやパプスカルと混同される)であった。 | ||

| − | イナンナは少なくともウルク文化(前4000年頃- | + | イナンナは少なくともウルク文化(前4000年頃-前3100年頃)の時代にはシュメールで崇拝されていたが、アッカドのサルゴンによる征服以前はほとんど信仰されていなかった。サルゴン王の時代以降、イナンナはシュメールの神殿の中で最も広く崇拝される神となり[4][5]、メソポタミア各地に神殿を持つようになった<ref>Wolkstein, Kramer, 1983, pagexviii</ref><ref>Nemet-Nejat, 1998, page182</ref>。イナンナ/イシュタルの信仰は、様々な性儀礼と結びついていたと思われるが、この地域のシュメール人を継承・吸収した東セム語系の人々(アッカド人、アッシリア人、バビロニア人)にも受け継がれた。イナンナは特にアッシリアの人々に愛され、アッシリアの国神アシュールよりも上位に位置する神殿の最高神とされた。イナンナはヘブライ語の聖書に登場し、ウガリット語のアシュタルトやフェニキア語のアスタルテに大きな影響を与え、さらにギリシャ神話の女神アフロディーテの誕生にも影響を与えたとされる。イナンナへの信仰はその後も栄え、紀元1世紀から6世紀にかけて、キリスト教の影響により徐々に衰退していった。 |

| + | イナンナはシュメールの他のどの神よりも多くの神話に登場する<ref>Wolkstein, Kramer, 1983, pagexv</ref><ref>Penglase, 1994, pages42–43</ref><ref>Kramer, 1961, page101</ref>。また、ネルガルに匹敵するほど多くの称号や 別名を有していた<ref>Wiggermann, 1999, p216</ref>。神話の多くは、彼女が他の神の領域を引き継ぐというものである。彼女は、知恵の神エンキから文明のプラスとマイナスのすべてを表すメー(''mes'')を授かったと信じられていた。また、天空の神アンから[[エアンナ]]神殿を譲り受けたとされる。イナンナは双子の弟ウトゥ(後のシャマシュ)と共に神の正義を執行した。自分の権威に挑戦したエビ山(Mount Ebih)を破壊し、寝込みを襲った庭師シュカレトゥダ(Shukaletuda)に怒りを爆発させ、ドゥムジを殺害した神の報復として盗賊女ビルル(Bilulu)を追跡して殺害したのである。アッカド語版の『ギルガメシュ叙事詩』では、イシュタルがギルガメシュに配偶者になるよう求めている。ギルガメシュがそれを拒否すると、彼女は'''天の雄牛を解き放ち'''、エンキドゥを死なせてしまい、その後ギルガメシュは自分の死と向き合うことになる。 | ||

| + | イナンナ/イシュタルの最も有名な神話は、姉のエレシュキガルが支配する古代メソポタミアの冥界への降臨とそこからの帰還を描いた物語である。エレシュキガルの玉座に着いた彼女は、冥界の7人の審判によって有罪とされ、死に追いやられる。3日後、ニンシュブルはすべての神々にイナンナを連れ戻すように懇願する。エンキだけは、イナンナを救うために、性のない2人の人間を送り込んだ<ref group="私注">アッティスのように去勢したもの、あるいは異性の扮装をした者を連想させる。</ref>。彼らはイナンナを冥界から追い出すが、冥界の守護者であるガラは彼女の夫ドゥムジをイナンナの代わりとして冥界に引きずり下ろす。やがてドゥムジは1年の半分を天に帰ることを許され、姉妹のゲシュティアンナは残りの半分を冥界にとどまり、季節が循環することになる。 | ||

| − | + | == 呼称 == | |

| + | その名は「nin-anna」(天の女主人)を意味するとされている<ref name="#1">アンソニー・グリーン監修『メソポタミアの神々と空想動物』p.24、山川出版社、2012/07</ref>。 | ||

| − | + | ウルクにあったイナンナのための神殿/寺院の名は「E-ana」(エアンナ、「天([[アヌ (メソポタミア神話)|アヌ]])の家」の意味)であった。 | |

| − | + | イナンナのシュメール語の別名は「nin-edin」(エデンの女主人)、「Inanna-edin」(エデンのイナンナ)であった。彼女の夫である[[タンムーズ|ドゥムジ]]のシュメール語の別名は「{mulu-edin」(エデンの主)であった。 | |

| − | + | アッカド帝国(Akkadian Empire|en)期には「[[イシュタル]]」(新アッシリア語: DINGIR INANNA)と呼ばれた。[[イシュタル]]はフェニキアの女神[[アスタルト|アスタルテ]]やシリアの女神[[アナト]]と関連し、古代ギリシアでは[[アプロディーテー]]と呼ばれ、ローマのヴィーナス([[ウェヌス]])女神と同一視されている<ref name="#1"/>。 | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | == 語源 == | |

| + | イナンナとイシュタルはもともと無関係な別の神であったが<ref>Leick, 1998, p87, Black Green, 1992, p108, Wolkstein Kramer, 1983, pxviii, Collins, 1994, p110-111, Brandão, 2019, p43</ref>、アッカドのサルゴンの時代に混同され、実質的に同じ女神が2つの名前で呼ばれるようになったと学者たちは考えている<ref>Leick, 1998, p87, Black Green, 1992, p108, Wolkstein Kramer, 1983, pxviii, xv, Collins, 1994, p=110-111</ref>。(アッカド語のAna Kurnugê, qaqqari la târi, Sha naqba īmuruがイシュタルの名を用いているほかは、すべてイナンナの名を用いたテキストである<ref>Brandão, 2019, p65</ref>。) イナンナの名前はシュメール語で「天国の女性」を意味するnin-an-akに由来すると考えられるが<ref>Leick, 1998, page86</ref><ref>Harris, 1991, pages261–278</ref>、イナンナの楔形記号(𒈹)は女性(''lady''、シュメール語:nin、楔型文字: 𒊩𒌆 SAL.TUG2)と空(''sky''、シュメール語:an、楔型文字: 𒀭 AN)を合字したものではないのではある<ref>Harris, 1991, pages261–278</ref><ref>Leick, 1998, page86</ref><ref>Wolkstein, Kramer, 1983, pagesxiii–xix</ref>。こうしたことから、初期のアッシリア学者の中には、イナンナはもともと原ユーフラテスの女神で、後にシュメールの神殿に受け入れられたのではないかと考える者もいた。この考えは、イナンナが若く、他のシュメールの神々とは異なり、当初は明確な責任範囲を持たなかったと思われることから支持された<ref>Harris, 1991, pages261–278</ref>。 シュメール語以前にイラク南部にプロト・ユーフラティア語の基層言語が存在したという見方は、現代のアッシリア学者にはあまり受け入れられていない<ref>Rubio, 1999, pages1–16</ref>。 | ||

| − | = | + | イシュタルという名前は、アッカド、アッシリア、バビロニアの前サルゴン時代と後サルゴン時代の人名に登場する<ref>Collins, 1994, page110</ref>。 その名はセム語由来<ref>Leick, 1998, page96</ref><ref>Collins, 1994, page110</ref>で、後世のウガリットやアラビア南部の碑文に登場する西セム語の神アッター(Attar)の名前に語源的に関連していると考えられる<ref>Leick, 1998, page96</ref><ref>Collins, 1994, page110</ref><ref group="私注">ヨーロッパには[[アルティオ]]という女神がいる。</ref>。開けの明星は兵法を司る男性神、宵の明星は愛術を司る女性神として考えられていたのかもしれない<ref>Collins, 1994, page110</ref><ref group="私注">元はどちらも女神であったものが、軍神としての要素のものが男神に変えられたものではないだろうか。</ref>。アッカド人、アッシリア人、バビロニア人の間では、やがて男性神の名が女性神の名に取って代わったが<ref>Collins, 1994, pages110–111</ref>、イナンナとの広範囲な習合により、名前は男性形であってもイシュタルは女性としてとどまった<ref>Collins, 1994, pages110–111</ref>。 |

| − | |||

| − | + | == 起源と発展 == | |

| + | [[File:Wall_plaque_showing_libation_scene_from_Ur,_Iraq,_2500_BCE._British_Museum_(libation_detail).jpeg|thumb|350px|神殿の扉の両側にイナンナの輪柱があり、裸の信者が盃を捧げている<ref name = priestess>Meador, Betty De Shong (2000). ''[https://books.google.co.jp/books?id=B45PvLlj3ogC&pg=PA14&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false Inanna, Lady of Largest Heart: Poems of the Sumerian High Priestess Enheduanna.]'' University of Texas Press. pp. 14–15. ISBN 978-0-292-75242-9.</ref>。]] | ||

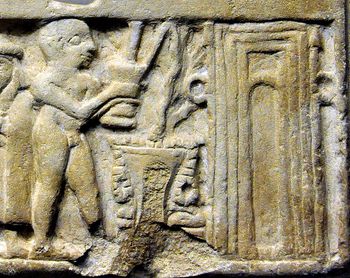

| + | [[File:Inanna_ring_posts_on_the_Warka_vase.jpeg|thumb|200px|女神イナンナの紋章、紀元前3000年頃<ref>Site officiel du musée du Louvre, http://cartelfr.louvre.fr/cartelfr/visite?srv=car_not_frame&idNotice=9643 , cartelfr.louvre.fr</ref>。ワルカの花瓶(Warka Vase)。]] | ||

| + | イナンナは、他のどの神よりも明確で矛盾した側面を持つため、古代シュメールの多くの研究者に問題を提起してきた<ref>Vanstiphout, 1984, pages225–228</ref>。彼女の起源については、大きく分けて2つの説がある<ref>Vanstiphout, 1984, page228</ref>。第一の説は、イナンナはシュメール神話に登場する、それまで全く関係のなかった複数の神々が、全く異なる領域を持つ神々と習合した結果生まれたとするものである<ref>Vanstiphout, 1984, page228</ref><ref>Brandão, 2019, p43</ref>。第二の説は、イナンナはもともとセム系の神で、シュメールのパンテオンが完全に構築された後に参入し、まだ他の神に割り当てられていないすべての役割を担ったとするものである<ref>Vanstiphout, 1984, pages228–229</ref>。 | ||

| − | + | ウルク時代(前4000年頃〜前3100年頃)、イナンナはすでにウルクの都市と結び付いていた<ref>Black, Green, 1992, page108</ref>。この時代、環状の頭部を持つ門柱のシンボルはイナンナと密接な関係があった<ref>Black, Green, 1992, page108</ref>。有名な「ウルクの壷([Uruk Vase)」(ウルク3世時代の祭祀具の堆積物から発見)は、裸の男たちが椀や器、農作物の入った籠など様々な物を運び<ref>Suter, 2014, page551</ref>、支配者と向き合う女性像に羊や山羊を連れていく姿が描かれている<ref>Suter, 2014, pages550–552</ref>。女性はイナンナの象徴である門柱の2本のねじれた葦の前に立ち<ref>Suter, 2014, pages550–552</ref>、男性は箱と杯の束を持っているが、これは後の楔形文字で神殿の高僧を意味するものである<ref>Suter, 2014, pages552–554</ref>。 | |

| − | + | ジェムデット・ナスル時代(紀元前3100年頃〜2900年頃)の印章には、ウル、ラルサ、ザバラム、ウルム、アリナ、そしておそらくケシュなど、様々な都市を表す記号が一定の順序で描かれている<ref>Van der Mierop, 2007, page55</ref>。このリストには、ウルクでイナンナ信仰を支える都市からイナンナへの寄進が報告されていることが反映されていると思われる<ref>Van der Mierop, 2007, page55</ref>。初期王朝時代(前2900年頃〜前2350年頃)のウルの第1期遺跡からは、イナンナのロゼットシンボルと組み合わせた、少し順序の異なる同様の印章が大量に発見されている<ref>Van der Mierop, 2007, page55</ref>。この印章は、イナンナの崇拝のために用意された材料を保存するための倉庫を封印するために使用された<ref>Van der Mierop, 2007, page55</ref>。 | |

| − | + | 紀元前2600年頃のキシュのアガ王の腕輪、紀元前2400年頃のルガル=キサルシ王の石版など、イナンナの名を記した様々な碑文が知られている。 | |

| − | |||

| − | + | <blockquote>"全土の王アンと、その愛人イナンナのために、キシュの王ルガル=キサルシは中庭の壁を築いた。"<br /> | |

| + | - ルガル=キサルシの碑文<ref>Maeda, 1981, p8</ref>。</blockquote> | ||

| − | + | アッカド帝国のサルゴンによる征服後のアッカド時代(前2334年頃〜前2154年頃)には、イナンナともともと独立していたイシュタルを広範囲に融合させ、事実上同一視されるようになった<ref>Leick, 1998, page87</ref><ref>Collins, 1994, pages110–111</ref>。 アッカドの詩人エンヘドゥアンナはサルゴンの娘で、イシュタルと同一視したイナンナへの賛美歌を数多く書いている<ref>Leick, 1998, page87</ref><ref>Collins, 1994, page111</ref>。その結果<ref>Leick, 1998, page87</ref>、イナンナ/イシュタル信仰は急増した<ref>Leick, 1998, page87</ref><ref>Black, Green, 1992, page108</ref><ref>Wolkstein, Kramer, 1983, pages=xviii, xv</ref>。エブラの発掘調査に早くから携わっていたアルフォンソ・アルキは、イシュタルはもともとユーフラテス川流域で崇拝されていた女神だと推測し、エブラとマリの両方の最も古い文献に、女神と砂漠のポプラとの関連が証明されていることを指摘した。アルキは、イナンナ、月の神(例えばシン)、性別の異なる太陽の神(シャマシュ/シャパシュ)を、メソポタミアと古代シリアの様々な初期セム族が共有する唯一の神であると考える。彼らはそれ以外、必ずしも重なり合わない異なる神殿を持っていたのである<ref>A. Archi, ''The Gods of Ebla'' [in:] J. Eidem, C.H. van Zoest (eds.), ''[https://www.nino-leiden.nl/publication/annual-report-nino-and-nit-2010 Annual Report NINO and NIT 2010]'', 2011, p. 3</ref>。 | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | == 信仰 == | |

| + | グウェンドリン・レイクは、前サルゴニア時代にはイナンナの崇拝はむしろ限定的であったと仮定しているが<ref>Leick, 1998, page87</ref>、他の専門家は、ウルク時代にはすでにウルクや他の多くの政治的拠点でイナンナは最も著名な神であったと主張している<ref>Asher-Greve Westenholz, 2013, p27, Kramer, 1961, p101, Wolkstein Kramer, 1983, pxiii–xix, Nemet-Nejat, 1998, p182</ref>。ニップル、ラガシュ、シュルパク、ザバラム、ウルに神殿があったが<ref>Leick, 1998, page87</ref>、主な信仰の中心はウルクのエアンナ神殿で<ref>Leick, 1998, page87</ref><ref>Black, Green, 1992, pages108–109</ref><ref>Harris, 1991, pages261–278</ref><ref>modern-day Warka, Biblical Erech</ref>、その名は「天国の家」(シュメール語:e2-anna、楔形文字:𒂍𒀭 E2.AN)を意味する<ref>''é-an-na'' means "sanctuary" ("house" + "Heaven" ["An"] + genitive)(Halloran, 2009)</ref> 。この紀元前4千年の都市の本来の守護神は「アン」であったとする研究もある<ref>Harris, 1991, pages261–278</ref>。イナンナに捧げられた後、この神殿には女神の巫女が住んでいたようである<ref>Harris, 1991, pages261–278</ref>。ザバラムはウルクに次いで初期のイナンナ信仰の重要な拠点であった。都市の名前は一般的にMUŠ3、UNUGと書かれ、それぞれ "イナンナ" と "聖域" を意味していた<ref>Asher-Greve, Westenholz, 2013, p42</ref>。 ザバラムの都市女神はもともと別の神であった可能性があるが、その女神信仰はかなり早い時期にウルク人の女神に吸収された<ref>Asher-Greve, Westenholz, 2013, p42</ref>。ヨアン・グッドニック・ウェステンホルツは、ザメの讃歌でイシュタランと結びついたNin-UM(読みと意味は不明)という名の女神が、ザバラムのイナンナの本来の姿であると提唱した<ref>Asher-Greve, Westenholz, 2013, p50</ref>。 | ||

| − | + | 古アッカド時代には、イナンナはアガデの都市に関連するアッカドの女神イシュタルと習合した<ref>Asher-Greve, Westenho, z, 2013, p62</ref>。 この時代の讃美歌には、アッカド人のイシュタルが、ウルクのイナンナ、ザバラムのイナンナと並んで「ウルマシュのイナンナ」と呼ばれているものがある<ref>Asher-Greve, Westenholz, 2013, p62</ref>。 イシュタル信仰とイナンナとの習合はサルゴンとその後継者によって奨励され<ref>Asher-Greve, Westenholz, 2013, p62</ref>、その結果イシュタルはメソポタミアのパンテオンの中で最も広く崇拝される神々の一つとなるに至った<ref>Leick, 1998, page87</ref>。サルゴン、ナラム-シン、シャル-カリ-シャリーの碑文では、イシュタルが最も頻繁に登場する神である<ref>Asher-Greve, Westenholz, 2013, p172</ref>。 | |

| − | + | 古バビロニア時代には、前述のウルク、ザバラム、アガデのほか、イリプが主な信仰の中心地であった<ref>Asher-Greve, Westenholz, 2013, p79</ref>。また、彼女の信仰はウルクからキシュに伝わった<ref>Asher-Greve, Westenholz, 2013, p21</ref>。 | |

| − | + | 後世、ウルクでの信仰が盛んになる一方で<ref>Black, Green, 1992, page99</ref>、上メソポタミア王国のアッシリア(現在のイラク北部、シリア北東部、トルコ南東部)、特にニネヴェ、アシュスール、アルベラ(現在のエルビル)でイシュタルの信仰が盛んになった<ref>Guirand, 1968, page58</ref>。アッシュールバニパル王の時代には、イシュタルはアッシリアの国神アシュールをも凌ぐ、アッシリアのパンテオンの中で最も重要で広く崇拝される神々に成長した<ref>Black, Green, 1992, page99</ref>。アッシリアの第一神殿で発見された奉納品から、彼女が女性の間で人気のある神であったことがわかる<ref>Asher-Greve, Westenholz, 2013, p20</ref>。 | |

| − | + | 伝統的な性別の二元論に反対する者は、イナンナの信仰に深く関わっていた<ref>Leick, 2013, pages157–158</ref>。シュメール時代には、イナンナの神殿でガラ(gala)と呼ばれる神官たちが働き、哀歌や嘆きを奏でたという<ref>Leick, 2013, page285</ref>。ガラになった男性は女性の名を名乗ることもあり、その歌はシュメール語のエメ・サル(''eme-sal'')という方言で詠まれた。この方言は、文学作品では通常、女性の登場人物が話すためのものである。シュメールの諺には、ガラが男性とアナルセックスをすることに定評があったことを示唆するものもあるようだ<ref>Roscoe, Murray, 1997, page65</ref>。アッカド時代、イシュタルの神殿で女装して戦いの踊りを披露したイシュタルの召使がクーガルやアシンヌである<ref>Roscoe, Murray, 1997, pages65–66</ref>。アッカド語のことわざの中には、彼らが同性愛の性癖を持っていた可能性を示唆するものがいくつかあるようだ<ref>Roscoe, Murray, 1997, pages65–66</ref>。メソポタミアに関する著作で知られる人類学者グウェンドリン・レイクは、これらの人物を現代のインドのヒジュラになぞらえている<ref>Leick, 2013, pages158–163</ref>。アッカド語の讃美歌には、イシュタルが男性を女性に変えるという表現がある<ref>Roscoe, Murray, 1997, page66</ref><ref>Brandão, 2019, p63</ref>。 | |

| − | + | 紀元前20世紀後半、イナンナ信仰は、王がドゥムジに扮し、女神に扮したイナンナの大神官と儀式的に性交することで自らの正統性を確立する「聖なる結婚」の儀式があったと広く信じられていた<ref>Kramer, 1970</ref><ref>Nemet-Nejat, 1998, page196</ref><ref>Brandão, 2019, p56</ref><ref>Pryke, 2017, pages128–129</ref>。しかし、この考えには疑問があり、文学作品に描かれた神聖な結婚が何らかの物理的な儀式を伴うものかどうか、その儀式が実際の性交を伴うものか、単に性交の象徴的な表現にすぎないのか、研究者の間で議論が続けられている<ref>George, 2006, page6</ref><ref>Pryke, 2017, pages128–129</ref>。古代近東の研究者であるルイーズ・M・プライクによれば、現在ではほとんどの学者が、神聖な結婚が実際に演じられる儀式であったとすれば、それは象徴的な性交に過ぎないと主張しているそうだ<ref>Pryke, 2017, page129</ref>。 | |

| − | + | イシュタル信仰は長い間、神聖な売春を伴うと考えられていたが<ref>Day, 2004, p15–17, Marcovich, 1996, p49, Guirand, 1968, p58, Nemet-Nejat, 1998, p193</ref>、現在では多くの学者の間で否定されている<ref>Assante, 2003, p14–47, Day, 2004, p2–21, Sweet, 1994, p85–104, Pryke, 2017, p61</ref>。『イシュタリトゥム(''ishtaritum'')』として知られるヒエログループはイシュタルの神殿で働いていたとされるが<ref>Marcovich, 1996, page49</ref>、そうした巫女が実際に性行為を行ったかどうかは不明であり<ref>Day, 2004, pages2–21</ref>、現代の学者も何人かそうでないと論じている<ref>Sweet, 1994, pages85–104</ref><ref>Assante, 2003, pages14–47</ref>。古代近東の女性たちは、イシュタルを崇拝し、灰で焼いたケーキ(カマーン・トゥムリ、''kamān tumri'')を捧げた<ref>Ackerman, 2006, pages116–117</ref>。この種の奉納は、アッカド語の讃美歌に記されている<ref>Ackerman, 2006, page115</ref>。マリで発見されたいくつかの粘土のケーキ型は、大きなお尻で胸を押さえた裸の女性の形をしている<ref>Ackerman, 2006, page115</ref>。この型から作られたケーキは、イシュタル自身を表現するためのものであったとする学者もいる。 | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | == イコノグラフィー == | |

| + | === シンボル === | ||

| + | [[File:Kudurru Melishipak Louvre Sb23 n02.jpeg|thumb|350px|八芒星はイナンナ/イシュタルの最も一般的なシンボルであった<ref>Black, Green, 1992, pp156, 169–170</ref><ref>Liungman, 2004, page228</ref>。ここでは、紀元前12世紀のメリ・シパクII世の境界石に、彼女の兄シャマシュ(シュメール語でウトゥ)の太陽ディスク、彼女の父シンの三日月(シュメール語でナンナ)とともに表示されている。]] | ||

| + | [[File:Ishtar_Eshnunna_Louvre_AO12456.jpeg|thumb|280px|バビロニアのエシュヌナから出土したイシュタルのテラコッタレリーフ(紀元前2千年初頭)]] | ||

| + | [[File:Winged_goddess-AO6501-IMG_0638-black.jpeg|thumb|280px|ラルサ出土の翼を持つイシュタルのレリーフ(紀元前2千年紀)]] | ||

| + | イナンナ/イシュタルの最も一般的なシンボルは八芒星であった<ref>Black, Green, 1992, pp156, 169–170</ref>が、正確な点の数は時々異なる<ref>Liungman, 2004, page228</ref>。また、六芒星も頻繁に登場するが、その象徴的な意味は不明である<ref>Black, Green, 1992, page170</ref><ref group="私注">アルコルか北極星ではないだろうか。</ref>。'''八芒星はもともと天と一般的な関連性を持っていた'''ようだが<ref>Black, Green, 1992, pages169–170</ref>、古バビロニア時代(前1830頃 - 前1531頃)には、特に金星と関連付けられるようになり、イシュタルはそれと同一視されるようになった<ref>Black, Green, 1992, pages169–170</ref>。この時期から、イシュタルの星は通常、円盤の中に収められるようになった<ref>Black, Green, 1992, page170</ref>。後のバビロニア時代には、イシュタルの神殿で働く奴隷に八芒星の印章が押されることもあったという<ref>Black, Green, 1992, page170</ref><ref>Nemet-Nejat, 1998, pages193–194</ref>。境界石や円筒印章には、シン(シュメール語でナンナ)の象徴である三日月やシャマシュ(シュメール語でウトゥ)の象徴である虹色の太陽円盤と一緒に八芒星が描かれることもある<ref>Liungman, 2004, page228</ref>。 | ||

| − | + | イナンナの楔形文字の表意文字は、葦の鉤状のねじれた結び目で、豊饒と豊穣の象徴である倉の門柱を表している<ref>Jacobsen, 1976</ref>。このロゼットはイナンナのもう一つの重要なシンボルであり、イナンナとイシュタルの習合後にもイシュタルのシンボルとして使われ続けている<ref>Black, Green, 1992, page156</ref>。新アッシリア時代(紀元前911〜609年)には、ロゼットは八芒星に取って代わり、イシュタルの主要なシンボルとなった可能性がある<ref>Black, Green, 1992, pages156–157</ref>。アッシュール市のイシュタル神殿は、多数のロゼットで飾られていた<ref>Black, Green, 1992, page156</ref>。 | |

| − | + | イナンナ/イシュタルはライオンと関連しており<ref>Black, Green, 1992, page118</ref><ref>Collins, 1994, pages113–114</ref>、シュメール時代、古代メソポタミア人はライオンを権力の象徴とみなしていた<ref>Black, Green, 1992, page118</ref>。ニップルのイナンナ神殿から出土した緑泥石製の鉢には、大蛇と戦う大きなネコが描かれており<ref>Collins, 1994, pages113–114</ref>、鉢に刻まれた楔形文字には「イナンナと蛇」とあり、ネコが女神を表していると考えられていることが示されている<ref>Collins, 1994, pages113–114</ref><ref group="私注">これは古代エジプトの「太陽の猫」とアペプのようなものだろうか。</ref>。アッカド時代には、イシュタルはライオンを属性とする重武装の女神として描かれることが多かった<ref>Black, Green, 1992, pp119</ref>。 | |

| − | + | 鳩はイナンナ/イシュタルに関連する著名な動物でもある<ref>Lewis, Llewellyn-Jones, 2018, page=335</ref><ref>Botterweck, Ringgren, 1990, page35</ref>。鳩は、紀元前3千年紀の初めにはイナンナに関連する祭具に描かれていた<ref>Botterweck, Ringgren, 1990, page35</ref>。紀元前13世紀のアシュシュルのイシュタル神殿から鉛製の鳩の置物が発見され<ref>Botterweck, Ringgren, 1990, page35</ref>、シリアのマリの壁画には、イシュタル神殿のヤシの木から巨大な鳩が姿を現しており<ref>Lewis, Llewellyn-Jones, 2018, page335</ref>、女神自身が鳩の姿をとることもあったと考えられている<ref>Lewis, Llewellyn-Jones, 2018, page335</ref>。 | |

| − | === | + | === 金星の女神として === |

| − | + | イナンナは金星と関連しており、金星の名前はローマ時代のヴィーナスに由来している<ref>Black, Green, 1992, pages108–109,</ref><ref>Nemet-Nejat, 1998, page203</ref><ref>Black, Green, 1992, pages108–109</ref>。いくつかの讃美歌は、イナンナを惑星ヴィーナスの女神または擬人化として讃えている<ref>Cooley, 2008, pages161–172</ref>。神学教授のジェフリー・クーリーは、多くの神話において、イナンナの動きは天空の金星の動きと対応しているのではないかと論じている<ref>Cooley, 2008, pages161–172</ref>。イナンナの冥界への降臨は、他の神々とは異なり、冥界に降臨して天に戻ることができる。金星も同じように、西に沈み、東に昇るように見える<ref>Cooley, 2008, pages161–172</ref>。冒頭の賛美歌では、イナンナが天界を離れ、山々と推定されるクルに向かう様子が描かれており、イナンナが西に昇り、沈む様子が再現されている<ref>Cooley, 2008, pages161–172</ref>。『イナンナとシュカレトゥダ』では、シュカレトゥダがイナンナを探して天を駆け巡る様子が描かれている。これは、おそらく東と西の地平を探っているのだろう<ref>Cooley, 2008, pages163–164</ref>。同じ神話の中で、イナンナは自分を襲った相手を探しながら、天空の金星の動きと呼応するような動きを何度もしている<ref>Cooley, 2008, pages161–172</ref>。 | |

| − | + | 金星の動きは不連続に見えるため(太陽に近いため何日も消えては別の地平線に再び現れる)、金星をひとつの存在として認識せず<ref>Cooley, 2008, pages161–172</ref>、それぞれの地平線にある朝星と夕星の2つの別の星だとする文化もあった<ref>Cooley, 2008, pages161–172</ref>。しかし、ジェムデット・ナスル時代の円筒印章は、古代シュメール人が朝星と夕星が同じ天体であることを知っていたことを示している<ref>Cooley, 2008, pages161–172</ref>。 金星の不連続な動きは、神話やイナンナの二面性に関連する<ref>Cooley, 2008, pages161–172</ref>。 | |

| − | + | 現代の占星術では、イナンナが冥界に落ちる話は、金星の逆行と関連した天文現象に言及したものであると認識されている。逆行中の金星が太陽と下交差する7日前に、夕方の空から姿を消す。この消失から連接までの7日間が、降臨神話のベースとなった天文現象であると見られている。連接後、さらに7日間を経て、金星が朝の星として現れ、これが冥界からの上昇に対応する<ref>Caton, 2012</ref><ref>Meyer, n.d.</ref>。 | |

| − | + | アヌニートゥとしてのイナンナは、黄道十二宮の最後の星座である魚座の東の魚と関連していた<ref>Foxvog, 1993, page106</ref><ref>Black, Green, 1992, pages34–35</ref>。彼女の配偶者であるドゥムジは、連続する第一の星座である牡羊座と関連していた<ref>Foxvog, 1993, page106</ref>。 | |

| − | + | == 特徴 == | |

| − | + | シュメール人は、イナンナを戦いと愛の女神として崇拝していた<ref>Black, Green, 1992, page108</ref>。イナンナの物語は、他の神々が固定的な役割と限られた領域を持つのとは異なり、征服から征服へと移り変わっていく姿を描いている<ref>Vanstiphout, 1984, pages225–228</ref><ref>Penglase, 1994, pages15–17</ref>。彼女は若く、気性が荒く、自分に与えられた以上の権力を常に求めているように描かれていた<ref>Vanstiphout, 1984, pages225–228</ref><ref>Penglase, 1994, pages15–17</ref>。 | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | </ | ||

| − | + | イナンナは愛の女神として崇拝されていたが、結婚の女神でもなければ、母なる女神とみなされることもなかった<ref>Black, Green, 1992, pp108–9</ref><ref>Leick, 2013, pages65–66</ref>。 アンドリュー・R・ジョージは、「あらゆる神話によれば、イシュタルは(中略)気質的にそのような職務には向いていなかった」とまで言っている<ref>George, 2015, p8</ref>。ジュリア・M・アッシャー・グレイヴは、イナンナが母神でないために特に重要であったとさえ(Asher-Greveが)提唱している<ref>Asher-Greve, Westenholz, 2013, p140, " Asher-Greve 2003; cf. Groneberg (1986a: 45) argues that Inana is significant because she is ''not'' a mother goddess [...]"</ref>。イナンナは愛の女神として、メソポタミア人が呪文を唱える際によく定量的<sup>''(要出典、August 2022)''</sup>に呼び出された<ref>Asher-Greve Julia M., Joan Goodnick Westenholz, Images, Orbis Biblicus et Orientalis: 259, Goddesses in Context: On Divine Powers, Roles, Relationships and Gender in Mesopotamian Textual and Visual Sources, 2013, https://www.zora.uzh.ch/id/eprint/135436/1/Asher-Greve_Westenholz_2013_Goddesses_in_Context.pdf, Fribourg, Academic Press, 2013, page242, isbn:9783525543825, 26 August 2022<br />『グラハム・カニンガム (1997: 171)によれば、呪文は「象徴的同一性の形式」と関係があり、いくつかの女神との象徴的同一性は、例えば[...]イナナとナナヤとのセックスと愛に関する事項[...]など、その神の機能または領域に関係していることは明らかであるように思われる。』 </ref>。 | |

| − | |||

| − | + | イナンナの冥界への降臨では、イナンナは恋人ドゥムジに対して非常に気まぐれな態度で接している<ref>Black, Green, 1992, pp108–9</ref>。イナンナのこのような性格は、後のアッカド語標準訳『ギルガメシュ叙事詩』の中で、ギルガメシュがイシュタルの恋人たちへのひどい仕打ちを指摘する際に強調されている<ref name="Gilgamesh' p. 86">''Gilgamesh'', p. 86</ref><ref>Pryke, 2017, page146</ref>。しかし、アッシリア学者のディーナ・カッツによれば、降臨神話におけるイナンナとドゥムジの関係の描写は異例であるとのことである<ref>Katz, 1996, p93-103</ref><ref>Katz, 2015, p67-68</ref>。 | |

| − | + | イナンナはシュメールの軍神の一人としても崇拝されていた<ref>Black, Green, 1992, pages108–109</ref><ref>Vanstiphout, 1984, pages226–227</ref>。彼女に捧げられた讃美歌のひとつに、こう書かれている。「彼女は、自分に従わない者たちに対して'''混乱と混沌を引き起こし、殺戮を加速し、恐ろしい輝きをまとって破壊的な洪水を誘発する'''。 争いや戦いのスピードが速く、疲れ知らずで、サンダルを履くのが彼女のゲームだ<ref>Enheduanna pre 2250 BCE A hymn to Inana (Inana C), id:4.07.3, 2003, The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature, http://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/cgi-bin/etcsl.cgi?text=t.4.07.3#, at:=lines 18–28, ETCSL 4.07.3</ref>。」戦いそのものが「イナンナの踊り」と呼ばれることもあった<ref>Vanstiphout, 1984, page227</ref>。特にライオンにまつわるエピソードは、そんな彼女の性格を際立たせるものだった<ref>Asher-Greve, Westenholz, 2013, p203-204</ref>。軍神としてイルニナ(「勝利」)の名で呼ばれることもあったが<ref>Westenholz, 1997, p78</ref>、この諡号は他の神々にも適用され、さらにイシュタルではなくニンギシダ<ref>Wiggermann, 1999a, p369, 371</ref>につながる別個の女神として機能することもあった<ref>Wiggermann, 1997, p42</ref><ref>Streck, Wasserman, 2013, p184</ref><ref>Asher-Greve, Westenholz, 2013, p113-114</ref>。イシュタルの性質のこの側面を強調するもう一つの諡号は、アヌニトゥ(「武勇なるもの」)であった<ref>Asher-Greve, Westenholz, 2013, p71</ref>。イルニナ同様、アヌニトゥも独立した神である可能性があり、ウル3世の文書で初めて証明された<ref>Asher-Greve, Westenholz, 2013, |p286</ref>。 | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | </ref> | ||

| − | + | アッシリアの王家の呪法は、イシュタルの主要な機能の両方を同時に呼び出すもので、効力と武勇を同様に取り除くためにイシュタルを呼び出した<ref>Zsolnay, 2010, p397-401</ref>。メソポタミアの文献によると、王が軍隊を率い、敵に勝利するような英雄的な特徴と性的能力は、相互に関連していると考えられていたようである<ref>Zsolnay, 2010, p393</ref>。 | |

| − | + | イナンナ/イシュタルは女神でありながら、その性別が曖昧になることがあった<ref>Asher-Greve, Westenholz, 2013, p17</ref>。 ゲイリー・ベックマンは、「曖昧な性別識別」はイシュタル自身だけでなく、彼が「イシュタル型」と呼ぶ女神たち(シャウシュカ、ピニキール、ニンシアンナなど)の特徴であったと述べている<ref>Beckman, 1999, p25</ref>。後期の讃美歌には「彼女(イシュタル)はエンリルであり、ニニルである」というフレーズがあるが、これはイシュタルが高貴であると同時に、時として「二形」であることに言及しているのかもしれない<ref>Asher-Greve, Westenholz, 2013, p127</ref>。ナナヤの讃歌には、バビロンのイシュタルの男性的な側面が、より標準的なさまざまな記述とともに言及されている<ref>Asher-Greve, Westenholzm, 2013, p116-117</ref>。しかし、イロナ・ズソンラニーは、イシュタルを「男性的な役割を果たす女性的な人物」としか表現していない<ref>Zsolnay, 2010, p401</ref>。 | |

| − | + | == 家族 == | |

| + | イナンナの双子の兄は、太陽と正義の神ウトゥ(アッカド語ではシャマシュと呼ばれる)である<ref>Black, Green, 1992, pages108, 182</ref><ref>Wolkstein, Kramer, 1983, pagesx–xi</ref><ref>Pryke, 2017, page36</ref>。シュメールの文献では、イナンナとウトゥは非常に親密な関係であることが示されており<ref>Pryke, 2017, pages36–37</ref>、近親相姦に近い関係であるとする現代作家もいる<ref>Pryke, 2017, pages36–37</ref><ref>Black, Green, 1992, page183</ref>。 イナンナは冥界降臨の神話において、冥界の女王エレシュキガルを「姉」と呼んでいるが<ref>Black, Green, 1992, page77</ref><ref>Pryke, 2017, page108</ref>、シュメール文学において2人の女神が一緒に現れることはほとんどなく<ref>Pryke, 2017, page108</ref>、神名帳でも同じカテゴリーに位置づけられていない<ref>Wiggermann, 1997, p47-48</ref>。フルリ語の影響により、いくつかの新アッシリアの資料(例えば罰則条項)では、イシュタルはアダドとも関連付けられており、フルリ神話のシャウシュカとその兄テシュブの関係を反映している<ref>Schwemer, 2007, p157</ref>。 | ||

| − | + | イナンナはナンナとその妻ニンガルを両親とする伝承が最も一般的である<ref>Asher-Greve, Westenholz, 2013, p230</ref><ref>Wilcke, 1980, p80</ref>。その例は、初期王朝時代の神リスト<ref>Asher-Greve, Westenholz, 2013, p45</ref>、エンリルとニンリルがイナンナに力を授けたことを伝えるイシュメ・ダガンの賛歌<ref>Asher-Greve, Westenholz, 2013, p75</ref>、ナナヤへの後期シンクレティック賛歌<ref>Asher-Greve, Westenholz, 2013, p116</ref>、ハトゥサからのアッカドの儀式など様々な資料に存在している<ref>Beckman, 2002, p37</ref>。ウルクではイナンナは通常、天空神アンの娘とみなされていたとする著者もいるが<ref>Black, Green, 1992, page108</ref><ref>Leick, 1998, page88</ref><ref>Brandão, 2019, pp47, 74</ref>、アンを父親とする言及は、アンはナンナの祖先としての地位にあるので、アンの娘としての地位に言及しているだけという可能性もある<ref>Wilcke, 1980, p80</ref>。文学作品ではエンリルやエンキが彼女の父親と呼ばれることがあるが<ref>Black, Green, 1992, page108</ref><ref>Leick, 1998, page88</ref><ref>Brandão, 2019, p74</ref>、主要な神が「父親」であるという言及も、年功を示す諡号としてこの語が使われる例となり得る<ref>Asher-Greve Julia M., Asher-Greve Julia M., Westenholz Joan Goodnick, Joan Goodnick Westenholz, Facets of Change, Orbis Biblicus et Orientalis: 259, Goddesses in Context: On Divine Powers, Roles, Relationships and Gender in Mesopotamian Textual and Visual Sources, 2013, https://www.zora.uzh.ch/id/eprint/135436/1/Asher-Greve_Westenholz_2013_Goddesses_in_Context.pdf, Fribourg, Academic Press, 2013, page140, isbn:9783525543825, access-date:26 August 2022</ref>。 | |

| − | + | 羊飼いの神であるドゥムジッド(後のタンムズ)は通常イナンナの夫とされるが<ref>Wolkstein, Kramer, 1983, pagesx–xi</ref>、いくつかの解釈によればイナンナの彼に対する誠意は疑わしい<ref>Black, Green, 1992, page108</ref>。冥界降臨の神話の中で、彼女はドゥムジッドを見捨て、ガラの悪魔が自分の代わりとして彼を冥界に引きずり下ろすことを許可する<ref>Wolkstein, Kramer, 1983, pages71–84</ref><ref>Leick, 1998, page93</ref>。別の神話「ドゥムジの帰還」では、イナンナはドゥムジの死を悼み、最終的に1年の半分だけドゥムジを天界に戻して一緒に暮らせるようにすることを命じた<ref>Wolkstein, Kramer, 1983, page89</ref><ref>Leick, 1998, page93</ref>。ディーナ・カッツは、『イナンナの降臨』における二人の関係の描写は珍しいと指摘する<ref>Katz, 2015, p67-68</ref>。それは、ドゥムジの死に関する他の神話における二人の関係の描写とは似ておらず、その責任はほとんどイナンナではなく、悪魔や人間の盗賊にさえある<ref>Katz, 1996, p93-103</ref>。イナンナとドゥムジの出会いを描いた恋の詩は、研究者によって多くの類話が収集されている<ref>Peterson, 2010, p253</ref>。しかし、イナンナ/イシュタルは必ずしもドゥムジと関連しているわけではなく、イナンナ/イシュタルが地方に出現することもあった<ref>Asher-Greve, Westenholz, 2013, p80</ref>。 キシュでは、都市の主神ザババ(軍神)がイシュタルのその地方での配偶者とされていたが<ref>Asher-Greve, Westenholz, 2013, p78</ref>、古バビロニア時代以降、ラガシュから伝わったバウがその配偶者となり(メソポタミア神話によく見られる、軍神と薬神のカップル<ref>Asher-Greve, Westenholz, 2013, p38</ref>)、代わりにキシュのイシュタルを単独で崇め始めるようになったという<ref>Asher-Greve, Westenholz, 2013, p78</ref>。 | |

| − | |||

| − | + | イナンナは通常、子孫を持つとは記述されていないが<ref>Black, Green, 1992, page108</ref>、ルガルバンダの神話やウル第三王朝(前2112年頃 - 2004年頃)の一棟の碑文において、軍神シャラが彼女の息子として記述されている<ref>Black, Green, 1992, page173</ref>。 また彼女は時にルーラル<ref>Hallo, 2010, page233</ref><ref group="私注">ローマ神話のラレースとの関連は? [[ラールンダ]]の項へ。</ref>(他のテキストではニンスンの息子として記述)の母親と見なされたこともある<ref>Hallo, 2010, page233</ref>。ウィルフレッド・G・ランバートは、『イナンナの降臨』の文脈で、イナンナとルーラルの関係を「近いが特定できない」と表現している<ref>Lambert, 1987, p163-164</ref>。また、恋愛の女神であるナナヤを娘とみなす証拠も同様に少ない(歌、奉納式、誓約)が、いずれも神々の親密さを示す諡号に過ぎず、実際の親子を示すものではない可能性もある<ref>Drewnowska-Rymarz, 2008, p30</ref>。 | |

| − | + | === サッカル === | |

| − | + | イナンナの助祭(サッカル)は女神ニンシュブールであり<ref>Pryke, 2017, page94</ref>、イナンナと相互の献身的な関係であった<ref>Pryke, 2017, page94</ref>。いくつかのテキストでは、ニンシュブールはイナンナの仲間としてドゥムジのすぐ後に、彼女の親族の一部よりも前に記載されており<ref>Wiggermann, 1988, p228-229</ref>、あるテキストでは「愛する宰相、ニンシュブール」というフレーズも登場する<ref>Wiggermann, 1988, p228-229</ref>。別のテキストでは、イナンナの側近の神々のリストにおいて、もともとイナンナ自身の仮身であった可能性のあるナナヤ<ref>Wiggermann, 2010, p417</ref>よりもニンシュブールの方が先にリストアップされている<ref>Stol, 1998, p146</ref>。ヒッタイトの古文書から知られるアッカドの儀式文では、イシュタルのサッカルが彼女の家族(シン、ニンガル、シャマシュ)と共に呼び出されている<ref>Beckman, 2002, p37-38</ref>。 | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | </ref> | ||

| − | + | イナンナの側近として神リストに頻繁に登場するのは、ナナヤ女神(通常ドゥムジとニンシュブールのすぐ後ろに位置する)、カニスラ、ガズババ、ビジラだが、これらはいずれもこの文脈とは別に、さまざまな構成で互いに関連づけられるものだった<ref>Stol, 1998, p146</ref><ref>Drewnowska-Rymarz, 2008, p23</ref>。 | |

| − | + | == 他の神々との習合と影響 == | |

| + | サルゴンとその後継者の時代にはイナンナとイシュタルが完全に融合していたことに加え<ref>Asher-Greve, Westenholz, 2013, p62</ref>、程度の差こそあれ、多くの神々<ref>Asher-Greve, Westenholz, 2013, p109</ref>と習合していた。最も古い習合の賛美歌はイナンナに捧げられたものであり<ref>Asher-Greve, Westenholz, 2013, p48</ref>、初期王朝時代のものとされている<ref>Asher-Greve, Westenholz, 2013, p100</ref>。古代の書記によって編纂された多くの神名帳には、同様の女神を列挙した「イナンナ・グループ」の項目があり<ref>Behrens, Klein, 1998, p345</ref>、『アン=アヌム』(全7枚)のタブレットIVは、その内容のほとんどがイシュタルの同等者の名前、称号、様々な従者であることから「イシュタルのタブレット」として知られている<ref>Litke, 1998, p148</ref>。現代の研究者の中には、イシュタル型という言葉を用いて、この種の特定の人物を定義している人もいる<ref>Beckman, 1999, p26</ref><ref>Beckman, 2002, p37</ref>。ある地域の「すべてのイシュタル」に言及する文章もあった<ref>Beckman, 1998, p4</ref>。 | ||

| − | + | 後世、バビロニアではイシュタルの名が総称(「女神」)として使われることもあり、またイナンナの対語表記がBēltuとされ、さらに混同されることもあった<ref>Asher-Greve, Westenholz, 2013, p110-111</ref>。アッカド語で書かれたエラム語の碑文に「マンザット・イシュタル」という言葉があり、これは「マンザット女神」という意味であろう<ref>Potts, 2010, p487</ref>。 | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | === 具体的事例 === | |

| − | + | * '''[[アスタルト]]''': マリやエブラのような都市では、東セム語と西セム語の名前(イシュタルとアシュタルト)は基本的に互換性があるとみなされていた<ref>Smith, 2014, p35</ref>。しかし、西洋の女神はメソポタミアのイシュタルのような幽体離脱の性格を持っていないことが明らかである<ref>Smith, 2014, p36</ref>。ウガリット語の神々のリストと儀式のテキストは、地元の[[アスタルト]]をイシュタルとフルリのイシャラの両方と同一視している<ref>Smith, 2014, p39, 74-75</ref>。 | |

| + | * '''[[イシャラ]]''':イシュタルとの関連から<ref>Asher-Greve, Westenholz, 2013, p134</ref>、シリアの女神イシャラはメソポタミアにおけるイシュタル(およびナナヤ)と同様に「愛の女性」としてみなされるようになった<ref>Murat, 2009, p176</ref><ref>Wiggermann, 2010, p417</ref>。しかし、フルリ・ヒッタイトの文献では、イシャラは代わりに冥界の女神アラーニと結び付けられ、さらに誓いの女神として機能した<ref>Murat, 2009, p176</ref><ref>Taracha, 2009, p124, 128</ref>。 | ||

| + | * '''[[ナナヤ]]''':というのも、アッシリア学者のフランス・ウィッガーマンによれば、ナナヤの名前はもともとイナンナの呼称であった(おそらく「私のイナンナ!」という呼びかけの役割を果たした)ため、イナンナと非常に密接な関係にある女神であった<ref>Wiggermann, 2010, p417</ref>。ナナヤはエロティックな恋愛に関連していたが、やがて戦争的な側面も持つようになる(「ナナヤ・ユルサバ」)<ref>Asher-Greve, Westenholz, 2013, p282</ref>。ラルサではイナンナの機能は事実上3つの人格の間で分割され、イナンナ自身、愛の女神としてのナナヤ、星女神としてのニンシアンナからなる三位一体として崇拝された<ref>Asher-Greve, Westenholz, 2013, p92</ref>。イナンナ/イシュタルとナナヤは、しばしば詩の中で偶然あるいは意図的に混同された<ref>Asher-Greve, Westenholz, 2013, p116-117; 120</ref>。 | ||

| + | * '''[[ニネンガル]]''':当初は独立した存在であったが、古バビロニア時代から「ニネンガル」がイナンナの称号として使われ、神名帳では通常ニンシアンナと並んで「イナンナ・グループ」の一員となった<ref>Behrens, Klein, 1998, p343-345</ref>。「ニネンガル」の諡号としての用例は、ETCSLの「Hymn to Inana as Ninegala (Inana D)」と指定されているテキストに見られる。 | ||

| + | * '''[[ニニシナ]]''':また、特殊な例として、薬の女神ニニシナとイナンナが政治的な理由で習合を起こしたことがある<ref>Asher-Greve, Westenholz, 2013, p86</ref>。イシンは一時ウルクの支配権を失い、王権の源泉である女神をイナンナと同一視し(イナンナに似た戦いの性格を持たせ)、この問題を神学的に解決しようとしたのであろう<ref>Asher-Greve, Westenholz, 2013, p86</ref>。その結果、多くの文献でニニシナは、同じような名前のニンシアンナと類似していると見なされ、イナンナの化身として扱われるようになった<ref>Asher-Greve, Westenholz, 2013, p86</ref>。 その結果、ニニシナとイシン王との「神聖な結婚」の儀式が行われた可能性もある<ref>Asher-Greve, Westenholz, 2013, p270</ref> 。 | ||

| + | * '''[[ニンシアンナ]]''':は、性別が異なる金星の神である<ref>Asher-Greve, Westenholz, 2013, p92-93</ref>。ニンシアンナは、ラルサのリム・シン(彼は特に「私の王」という言葉を使った)やシッパル、ウル、ギルスの文書では男性として言及されているが、神名リストや天文文書では「星のイシュタル」と呼ばれており、イシュタルの金星の擬人化としての役割に関する呼称もこの神に当てられている<ref>Heimpel, 1998, p487-488</ref>。また、ニンシアンナは女性の神として知られていたところもあり、その場合は「天の赤い女王」と理解することができる<ref>Asher-Greve, Westenholz, 2013, p86</ref>。 | ||

| + | * '''[[ピニキル]]''':元々はエラムの女神で、メソポタミアで認識され、その結果、フルリ人やヒッタイト人の間で、機能が似ていることからイシュタルに相当する女神として認識されるようになった。神々のリストでは、彼女は星神(ニンシアンナ)として特定されている<ref>Beckman, 1999, p27</ref>。ヒッタイトの儀式では、彼女は<sup>d</sup>IŠTARという記号で識別され、シャマシュ、スエン、ニンガルが彼女の家族として言及され、エンキとイシュタルのサッカルも呼び出された<ref>Beckman, 2002, p37-39</ref>。ピニキルはエラムでは愛と性の女神<ref>Abdi, 2017, p10</ref>、天上の神(「天の愛人」)であった<ref>Henkelman, 2008, p266</ref>。イシュタルやニシアンナとの習合により、ピニキルはフルリ・ヒッタイトの資料では女性神、男性神として言及されている<ref>Beckman, 1999, p25-27</ref>。 | ||

| + | * '''[[シャウシュカ]]''':彼女の名前はフルリ・ヒッタイトの文献では<sup>d</sup>IŠTARという記号でしばしば記述された。メソポタミアでは「スバルトゥのイシュタル」という名で知られている<ref>Beckman, 1998, p1-3</ref>。彼女特有の要素は、後世、アッシリアのイシュタル神格(ニネベのイシュタル)と結びつけられることになる<ref>Beckman, 1998, p7-8</ref>。彼女の侍女ニナッタとクリッタは、アッシュールの神殿でイシュタルに仕える神々の輪の中に組み込まれた<ref>rantz-Szabó, 1983, p304</ref><ref>Wilhelm, 1989, p52</ref>。 | ||

| − | == | + | === 時代遅れの説 === |

| − | + | 過去に一部の研究者は、イシュタルをアムルゥに関連する西セム語のアティラート(アシェラ)のバビロニアにおける反映である小女神アシュラトゥと結び付けようとしたが<ref>Wiggins, 2007, p156</ref>、スティーブ・A・ウィギンズが実証したように、この説は根拠のないものであった<ref>Wiggins, 2007, p156</ref>。なぜなら、この2人が混同されていた、あるいは単に混同されていたという唯一の証拠は、イシュタルとアシュラトゥが同じ諡号を共有していたという事実であり[190]、しかし同じ諡号はマルドゥク、ニントゥル、ネガル、スエンにも適用されており<ref>Wiggins, 2007, p156</ref>、神名リストなどの資料にはさらなる証拠は見当たらなかったからだ<ref>Wiggins, 2007, p156-163</ref>。また、ウガリット語のイシュタルの同義語であるアスタルト(Ashtart)が、アモリ人によりアティラートと混同、混同された形跡はない<ref>Wiggins, 2007, p169</ref>。 | |

| − | + | == 神話のなかのイナンナ == | |

| + | === 系譜 === | ||

| + | イナンナは系譜上はアンの娘だが、月神ナンナ([[シン (メソポタミア神話)|シン]])の娘とされることもあり、この場合太陽神ウトゥ([[シャマシュ]])とは双子の兄妹で、冥界の女王[[エレシュキガル]]の妹でもある<ref>アンソニー・グリーン監修『メソポタミアの神々と空想動物』p.25、山川出版社、2012/07</ref>。夫にドゥムジ (メソポタミア神話)(Dumuzid the Shepherd)をいただく。子供は息子シャラ(Shara, Šara, シュメール語: 𒀭𒁈, <sup>d</sup>šara<sub>2</sub>, <sup>d</sup>šara)。別の息子ルラル(Lulal)はウトゥの女祭事(神官)ニンスンの息子ともされている。 | ||

| − | === | + | === エンキの紋章を奪う === |

| − | + | メソポタミア神話において、イナンナは知識の神[[エンキ]]の誘惑をふりきり、酔っ払ったエンキから、文明生活の恵み「'''[[メー]]'''」(水神であるエンキの持っている神の権力を象徴する紋章)をすべて奪い、エンキの差し向けたガラの悪魔の追跡から逃がれ、ウルクに無事たどりついた<ref group="私注">これは中国神話で述べるところの「[[不老不死の薬]]」のことと考える。</ref>。エンキはだまされたことを悟り、最終的に、ウルクとの永遠の講和を受け入れた。この神話は、太初において、政治的権威がエンキの都市エリドゥ(紀元前4900]頃に建設された都市)からイナンナの都市ウルクに移行するという事件(同時に、最高神の地位がエンキからイナンナに移ったこと)を示唆していると考えられる。 | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | === | + | === イナンナ女神の歌 === |

| − | + | シュメール時代の粘土板である『イナンナ女神の歌』よりイナンナは、[[ニンガル]]から生まれた魅力と美貌を持ち、[[龍]]のように速く飛び<ref>[http://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/cgi-bin/etcsl.cgi?text=t.4.07.5&charenc=j# 「イナンナ女神の歌」1-4]</ref>、南風に乗り[[アプスー]]から聖なる力を得た<ref>[http://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/cgi-bin/etcsl.cgi?text=t.4.07.5&charenc=j# 「イナンナ女神の歌」5-8]</ref>。母親ニンガルの胎内から誕生した際、すでにシタ(cita)とミトゥム(mitum)という2つの鎚矛を手にして生まれた<ref>[http://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/cgi-bin/etcsl.cgi?text=t.4.07.5&charenc=j# 「イナンナ女神の歌」9-12]</ref>。 | |

| − | == | + | === イナンナとフルップ(ハルブ)の樹 === |

| − | + | <sup>''(出典の明記、2018年2月)''</sup> | |

| − | + | ある日、イナンナはぶらぶらとユーフラテス河畔を歩いていると、強い南風にあおられて今にもユーフラテス川に倒れそうな「フルップ(ハルブ)の樹<ref>[Hulupp]-アッカド語で「'''生命の木'''」のこと。</ref>」を見つけた。あたりを見渡しても他の樹木は見あたらず、イナンナはこの樹が世界の領域を表す[[世界樹]]([[生命の木]])であることに気がついた。 | |

| + | |||

| + | そこでイナンナはある計画を思いついた。 | ||

| + | |||

| + | この樹から典型的な権力の象徴をつくり、この不思議な樹の力を利用して世界を支配しようと考えたのだ。 | ||

| + | |||

| + | イナンナはそれを[[ウルク]]に持ち帰り、聖なる園([[エデンの園|エデン]])に植えて大事に育てようとする。 | ||

| + | |||

| + | まだ世界はちょうど創造されたばかりで、その世界樹はまだ成るべき大きさには程遠かった。イナンナは、この時すでにフルップの樹が完全に成長した日にはどのような力を彼女が持つことができるかを知っていた。 | ||

| + | |||

| + | 「もし時が来たらならば、この世界樹を使って輝く王冠と輝くベッド(王座)を作るのだ」 | ||

| + | |||

| + | その後10年の間にその樹はぐんぐんと成長していった。 | ||

| + | |||

| + | しかし、その時[[ズー|(アン)ズー]]がやって来て、天まで届こうかというその樹のてっぺんに巣を作り、雛を育て始めた。 | ||

| + | |||

| + | さらに樹の根にはヘビが巣を作っていて、樹の幹には[[リリス]]が住処を構えていた。リリスの姿は大気と冥界の神であることを示していたので、イナンナは気が気でなかった。 | ||

| − | [[ | + | しばらくの後、いよいよこの樹から支配者の印をつくる時が来た時、リリスにむかって聖なる樹から立ち去るようにお願いした。 |

| + | |||

| + | しかしながら、イナンナはその時まだ神に対抗できるだけの力を持っておらず、リリスも言うことを聞こうとはしなかった。彼女の天真爛漫な顔はみるみるうちに失望へと変わっていった。そして、このリリスを押しのけられるだけの力を持った神は誰かと考えた。そして彼女の兄弟である太陽神[[シャマシュ|ウトゥ]]に頼んでみることになった。 | ||

| + | |||

| + | 暁方にウトゥは日々の仕事として通っている道を進んでいる時だった。イナンナは彼に声をかけ、これまでのいきさつを話し、助けを懇願した。ウトゥはイナンナの悩みを解決しようと、銅製の斧をかついでイナンナの聖なる園にやって来た。 | ||

| − | + | ヘビは樹を立ち去ろうとしないばかりかウトゥに襲いかかろうとしたので、彼はそれを退治した。ズーは子供らと高く舞い上がると天の頂きにまで昇り、そこに巣を作ることにした。リリスは自らの住居を破壊し、誰も住んでいない荒野に去っていった。 | |

| + | |||

| + | ウトゥはその後、樹の根っこを引き抜きやすくし、銅製の斧で輝く王冠と輝くベッドをイナンナのために作ってやった。彼女は「他の神々と一緒にいる場所ができた」ととても喜び、感謝の印として、その樹の根と枝を使って「プック(Pukku)とミック(Mikku)」(輪と棒)を作り、ウトゥへの贈り物とした<ref group="私注">イナンナには木を切り倒し、利用する職能神としての一面があるように思う。このような性質はヒッタイトの女神[[マリヤ]]にもあったと考える。</ref>。 | ||

| − | + | なお、この神話には、ウトゥの代わりに[[ギルガメシュ]]が同じ役割として登場する[[ギルガメシュ叙事詩|ヴァリエーション(変種)]]がある。 | |

| − | + | === イナンナの冥界下り === | |

| + | 天界の女王イナンナは、理由は明らかではないものの(一説にはイナンナは冥界を支配しようと企んでいた)、地上の七つの都市の神殿を手放し、姉のエレシュキガルの治める冥界に下りる決心をした。冥界へむかう前にイナンナは七つの[[メー]]をまとい、それを象徴する飾りなどで身を着飾って、忠実な従者である[[ニンシュブル]]に自分に万が一のことがあったときのために、力のある神[[エンリル]]、[[シン (メソポタミア神話)|ナンナ]]、[[エンキ]]に助力を頼むように申しつけた<ref>矢島、51 - 52頁。</ref><ref>岡田・小林、163頁。</ref>。 | ||

| − | + | 冥界の門を到着すると、イナンナは門番である[[ネティ]]に冥界の門を開くように命じ<ref>来訪の理由を問われ、エレシュキガルの夫[[グガランナ|グアガルアンナ]]の葬儀に出席することを口実にしたともされる(岡田・小林、163頁)。</ref>、ネティはエレシュキガルの元に承諾を得に行った。エレシュキガルはイナンナの来訪に怒ったが、イナンナが冥界の七つの門の一つを通過するたびに身につけた飾りの一つをはぎ取ることを条件に通過を許した。イナンナは門を通るごとに身につけたものを取り上げられ、最後の門をくぐるときに全裸になった。彼女はエレシュキガルの宮殿に連れて行かれて、七柱のアヌンナの神々に冥界へ下りた罪を裁かれた。イナンナは死刑判決を受け、エレシュキガルが「死の眼差し」を向けると倒れて死んでしまった。彼女の死体は宮殿の壁に鉤で吊るされた<ref>矢島。52 - 56頁</ref><ref>岡田・小林、164。</ref>。 | |

| − | [[ | ||

| − | '' | + | 三日三晩が過ぎ<ref>異聞では七年七ヶ月七日とも七年ともいわれる(岡田・小林、167頁)。</ref>、ニンシュブルは最初にエンリル、次にナンナに経緯を伝えて助けを求めたが、彼らは助力を拒んだ。しかしエンキは自分の爪の垢からクルガルラ(泣き女)とガラトゥル(哀歌を歌う神官)という者を造り、それぞれに「命の食べ物」と「'''命の水'''」を持って、先ずエレシュキガルの下へ赴き、病んでいる彼女を癒すよう、そしてその礼として彼女が与えようとする川の水と大麦は受け取らずにイナンナの死体を貰い受け、死体に「命の食べ物」と「命の水」を振りかけるように命じた。クルガルラとガラトゥルがエンキに命じられた通りにするとイナンナは起き上がった。しかし冥界の神々はイナンナが地上に戻るには身代わりに誰かを冥界に送らなければならないという条件をつけ、ガルラという精霊たちが彼女に付いて行った<ref>矢島、56 - 58頁</ref><ref>岡田・小林、164 - 165頁、但し、こちらではエレシュキガルの病を癒すこと、その礼としてイナンナの死体を求めることについての記載は無い。</ref>。 |

| − | + | まず、イナンナはニンシュブルに会った。ガルラたちは彼女を連れて行こうとしたが、イナンナは彼女が自分のために手を尽くしたことと喪に服してくれたことを理由に押しとどめた。次にシャラ神、さらにラタラク神に会うが、彼らも喪に服し、イナンナが生還したことを地に伏して喜んだため、彼らが自身に仕える者であることを理由に連れて行くことを許さなかった。しかし夫の神ドゥムジが喪にも服さず着飾っていたため、イナンナは怒り、彼を自分の身代わりに連れて行くように命じた。ドゥムジはイナンナの兄[[ウトゥ]]に救いを求め、憐れんだウトゥは彼の姿を蛇に変えた。ドゥムジは姉の[[ゲシュティンアンナ]]の下へ逃げ込んだが、最後には羊小屋にいるところを見つかり、地下の世界へと連れ去られた。その後、彼と姉が半年ずつ交代で冥界に下ることになった<ref>矢島、58 - 62頁。</ref><ref>岡田・小林、165 -166頁。</ref>。 | |

| − | + | == 王権を授与する神としてのイナンナ == | |

| + | イナンナ神は外敵を排撃する神としてイメージされており、統一国家形成期には王権を授与する神としてとらえられている。なお、それに先だつ領域国家の時代、および後続する統一国家確立期においては王権を授与する神は[[エンリル]](シュメール語: 𒀭𒂗𒇸)であり、そこには交代がみられる<ref>前田(2003)p.21</ref>。 | ||

| − | + | === ウルクの大杯 === | |

| + | 高さ1m強、石灰岩で造られた大杯。ドイツ隊によって発見され、イラク博物館に展示されていた<ref>前川和也『図説メソポタミア文明』p.6</ref>。最上段には都市の支配者が最高神イナンナに献納品を携え訪れている図像が描かれ、最下段には[[チグリス]]と[[ユーフラテス]]が、その上に主要作物、羊のペア、さらに逆方向を向く裸の男たちが描かれている<ref>前川和也『図説メソポタミア文明』p.8</ref>。図像はイナンナと[[ドゥムジ]]の「聖婚」を示し、当時の人々が豊穣を願う性的合一の儀式を国家祭儀にまで高めていた様子を教えている<ref>前川和也『図説メソポタミア文明』p.9</ref>。 | ||

| − | === | + | == シュメール語文献 == |

| + | === 起源的な神話 === | ||

| + | 「エンキと世界秩序の詩」([http://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/section1/tr113.htm%201.1.3 ETCSL 1.1.3])は、まずエンキ神とその宇宙組織の設立を描いている<ref>Kramer, 1963, pages172–174</ref>。詩の終盤、イナンナはエンキのもとにやってきて、自分以外の神々に領地と特別な力を与えてしまったと不満を漏らす<ref>Kramer, 1963, page174</ref>。イナンナは不当な扱いを受けたと宣言した<ref>Kramer, 1963, page182</ref>。これに対し、エンキは「すでに領域を持っているのだから、割り当てる必要はない」と言い放った<ref>Kramer, 1963, page183</ref>。 | ||

| − | + | 『ギルガメシュ叙事詩』([http://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/section1/tr1814.htm%201.8.1.4 ETCSL 1.8.1.4])<ref>Kramer, 1961, page30</ref>の前文にある「イナンナとフルップの木」の神話は、まだ権力が安定していない若いイナンナを中心にしている<ref>Wolkstein, Kramer, 1983, page141</ref><ref>Pryke, 2017, pages153–154</ref>。物語はクレイマーが[[ヤナギ]]かもしれないと同定した、ユーフラテス川の岸辺に生えるフルップの木<ref>Kramer, 1961, page33</ref><ref>Kramer, 1961, page33</ref>から始まる<ref>Fontenrose, 1980, page172</ref>。イナンナはこの木をウルクの自分の庭に移し、成長したら王座に造りかえるつもりだった<ref>Kramer, 1961, page33</ref><ref>Fontenrose, 1980, page172</ref>。木は成長し成熟するが、「魅力を知らない」蛇、[[アンズー]]鳥、そしてユダヤ伝承のリリスの前身であるシュメール人のリリトゥ(シュメール語でキ・シキル・リル・ラ・ケ)<ref>CDLI Tablet P346140, https://cdli.ucla.edu/search/archival_view.php?ObjectID=P346140, cdli.ucla.edu</ref>が木の中に住みつき、イナンナは悲しみで泣くことになる<ref>Kramer, 1961, page33</ref><ref>Fontenrose, 1980, page172</ref>。この物語では、彼女の兄として描かれている英雄ギルガメシュが現れ、大蛇を倒し、[[アンズー]]鳥とリリトゥを追い出している<ref>Kramer, 1961, pages33–34</ref><ref>Fontenrose, 1980, page172</ref>。ギルガメシュの仲間はこの木を切り倒し、その木を彫ってベッドと玉座を作り、イナンナに渡す<ref>Wolkstein, Kramer, 1983, page140</ref><ref>Fontenrose, 1980, page172</ref>。イナンナはピックとミック(それぞれ太鼓と太鼓台と思われるが、正確な特定は不明<ref>Kramer, 1961, page34</ref>)を作り、ギルガメッシュにその英雄的行為の報酬として渡す<ref>Wolkstein, Kramer, 1983, page9</ref><ref>Fontenrose, 1980, page172</ref><ref group="私注">メソポタミア神話での「'''木を切り倒す'''」エピソードと「'''女神の庭園'''」の物語である。イナンナがギルガメシュに与えた呪具は「邪気祓い」の道具だったかもしれない、と考える。日月蝕の際に道具を叩いて音を立て、天の邪気を払う習慣はモンゴル等にみられるように思う。([[射日神話]]、参照のこと)</ref>。 | |

| − | |||

| − | + | シュメールの「イナンナとウトゥ」讃歌には、イナンナが性の女神になるまでの経緯を描いた起源神話がある<ref>Leick, 1998, page91</ref>。讃美歌の冒頭で、イナンナは性について何も知らないので<ref>Leick, 1998, page91</ref>、兄のウトゥに頼んでクア(シュメールの冥界)に連れて行ってもらい<ref>Leick, 1998, page91</ref>、そこに生えている木の実を食べて<ref>Leick, 1998, page91</ref>、性の秘密をすべて明らかにしてもらう<ref>Leick, 1998, page91</ref>。ウトゥはそれに応じ、イナンナはクアでその実を味わい、知識を得る<ref>Leick, 1998, page91</ref>。この讃美歌は、エンキとニンフルサグの神話や、後の聖書のアダムとイブの物語に見られるのと同じモチーフが用いられている<ref>Leick, 1998, page91</ref>。 | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | </ | ||

| − | + | 「イナンナは農夫を好む」([http://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/section4/tr40833.htm%204.0.8.3.3 ETCSL 4.0.8.3.3])という詩は、イナンナとウトゥのちょっと戯れた会話から始まり、ウトゥは彼女に結婚する時期が来たことを徐々に明かしていく<ref>Kramer, 1961, page101</ref><ref>Wolkstein, Kramer, 1983, pages30–49</ref>。彼女は農夫のエンキムドゥと羊飼いのドゥムジに言い寄られる<ref>Kramer, 1961, page101</ref>。当初、イナンナは農夫を好んでいたが<ref>Kramer, 1961, page101</ref>、ウトゥとドゥムジは、農夫が彼女に与えることができる贈り物に対して、羊飼いはもっと良いものを与えることができると主張して、ドゥムジが夫としてふさわしいと次第に説得していく<ref>Kramer, 1961, pages102–103</ref>。結局、イナンナはドゥムジと結婚する<ref>Kramer, 1961, pages102–103</ref>。羊飼いと農夫は、互いに贈り物をすることで仲直りした<ref>Kramer, 1961, pages101–103</ref>。サミュエル・ノア・クレイマーは、この神話を後の聖書のカインとアベルの物語と比較している。両神話は、農夫と羊飼いが神の好意をめぐって競い合い、どちらの物語も最終的には神が羊飼いを選ぶからだ<ref>Kramer, 1961, page101</ref>。 | |

| − | + | === 征服と庇護 === | |

| + | 『イナンナとエンキ』([http://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/cgi-bin/etcsl.cgi?text=t.1.3.1#%20t.1.3.1 ETCSL t.1.3.1]) はシュメール語で書かれた長編詩で、ウル第三王朝(紀元前2112年頃 - 紀元前2004年頃)のものと考えられる<ref>Leick, 1998, page90</ref>。イナンナが水と人間の文化の神エンキから聖なるメーを奪う物語が書かれている<ref>Kramer, 1961, page66</ref>。古代シュメール神話では、メーは人間の文明を存在させる神々に属する神聖な力、または財産とされていた<ref>Black, Green, 1992, page130</ref>。メーはそれぞれ、人間の文化の一面を体現している<ref>Black, Green, 1992, page130</ref>。その内容は多岐にわたり、真理、勝利、助言といった抽象的な概念から、文字や織物といった技術、さらには法律、祭司職、王権、売春といった社会的な構成要素も詩の中に挙げられている。メーは、文明のあらゆる面において、プラスとマイナスの両方の力を与えると信じられていた<ref>Kramer, 1961, page66</ref>。 | ||

| − | + | 神話では、イナンナは自分の住むウルクからエンキの住むエリドゥに行き、エンキの神殿であるアプスーを訪れた<ref>Kramer, 1961, page65</ref>。イナンナはエンキのサッカルであるイシムドに迎えられ、食べ物や飲み物を差し出される<ref>Kramer, 1961, pages65–66</ref><ref>Wolkstein, Kramer, 1983, pages13–14</ref>。 イナンナはエンキと飲み比べを始めた<ref>Kramer, 1961, page66</ref><ref>Wolkstein, Kramer, 1983, page14</ref>。そして、エンキがすっかり酔ったところで、イナンナはエンキにメーを渡すように説得する<ref>Kramer, 1961, page66</ref><ref>Wolkstein, Kramer, 1983, pages14–20</ref>。イナンナは天の舟に乗ってエリドゥを脱出し、メーを携えてウルクへ向かった<ref>Kramer, 1961, pages66–67</ref><ref>Wolkstein, Kramer, 1983, page20</ref>。エンキは目を覚ますと、メーがいなくなっていることに気づき、イシムドにメーに何が起こったのか尋ねた<ref>Kramer, 1961, pages66–67</ref><ref>Wolkstein, Kramer, 1983, pages20–21</ref>。 イシムドは、エンキがそのすべてをイナンナに与えたと答えた<ref>Kramer, 1961, page67</ref><ref>Wolkstein, Kramer, 1983, page21</ref>。エンキは激怒し、イナンナがウルクの街にたどり着く前にメーを奪おうと、複数の獰猛な怪物たちをイナンナのもとに送り込んだ<ref>Kramer, 1961, pages67–68</ref><ref>Wolkstein, Kramer, 1983, pages20–24</ref>。エンキが送り込んだ怪物たちを、イナンナのサッカルであるニンシュブルが退治した<ref>Kramer, 1961, page68</ref><ref>Wolkstein, Kramer, 1983, pages20–24</ref><ref>Pryke, 2017, page94</ref>。 イナンナはニンシュブルの助けで、メーをウルクに持ち帰ることに成功した<ref>Kramer, 1961, page68</ref><ref>Wolkstein, Kramer, 1983, pages24–25</ref>。イナンナが逃げ出した後、エンキはイナンナと和解し、前向きな別れを告げた<ref>Wolkstein, Kramer, 1983, pages26–27</ref>。この伝説は、エリドゥという都市からウルクという都市への歴史的な権力移譲を表している可能性がある<ref>Harris, 1991, pages261–278</ref><ref>Green, 2003, page74</ref>。また、この伝説はイナンナが成熟し、天の女王になる準備が整ったことを象徴的に表現している可能性もある<ref>Wolkstein, Kramer, 1983, page146-150</ref>。 | |

| − | + | 「イナンナが天界を支配する」という詩は、極めて断片的ではあるが、イナンナがウルクのエアンナ神殿を征服する様子を描いた重要なものである<ref>Harris, 1991, pages261–278</ref>。イナンナと弟のウトゥの会話から始まり、イナンナはエアンナ神殿が自分たちの領地にないことを嘆き、自分のものにしようと決心する<ref>Harris, 1991, pages261–278</ref>。 このあたりから文章は断片的になってくるが<ref>Harris, 1991, pages261–278</ref>、漁師に道を教わりながら沼地を抜けて神殿にたどり着くまでの困難な道のりを描いていると思われる<ref>Harris, 1991, pages261–278</ref>。イナンナは最終的に父アンのもとに辿り着き、アンはイナンナの傲慢さにショックを受けながらも、彼女の成功と神殿が彼女の領地であることを認める<ref>Harris, 1991, pages261–278</ref>。本文は、イナンナの偉大さを説いた讃美歌で終わっている<ref>Harris, 1991, pages261–278</ref>。この神話は、ウルクにおけるアンの神官の権威が失墜し、イナンナの神官に権力が移ったことを表しているのだろう<ref>Harris, 1991, pages261–278</ref>。 | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | < | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | 叙事詩『エンメルカールとアラッタの主』([http://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/section1/tr1823.htm%201.8.2.3 ETCSL 1.8.2.3])の最初と最後に、イナンナが一瞬だけ登場する。この叙事詩は、ウルクとアラッタの都市間の対立を扱っている。しかし、そのような鉱物はアラッタにしかなく、まだ交易が行われていないため、資源を手に入れることができないのだ<ref>Vanstiphout, 2003, pages57–61</ref>。両都市の守護女神であるイナンナ<ref>Vanstiphout, 2003, page49</ref>は、詩の冒頭でエンメルカルの前に現れ<ref>Vanstiphout, 2003, pages57–63</ref>、アラッタよりもウルクを好むと告げる<ref>Vanstiphout, 2003, pages61–63</ref>。彼女はエンメルカールにアラッタの領主に使者を送り、ウルクに必要な資源を求めるよう指示した<ref>Vanstiphout, 2003, page49</ref>。叙事詩の大部分は、イナンナの寵愛をめぐって二人の王が繰り広げる大競争を中心に描かれている<ref>Vanstiphout, 2003, pages63–87</ref>。詩の最後にイナンナが再び現れ、エンメルカールに自分の都市とアラッタの間に交易を確立するように言って、対立を解決する<ref>Vanstiphout, 2003, page50</ref>。 | |

| − | === | + | === 正義の神話 === |

| − | + | イナンナとその弟のウトゥは神の正義を伝える者と見なされており<ref>Pryke, 2017, pages36–37</ref>、イナンナはその役割をいくつかの神話で例証している<ref>Pryke, 2017, pages162–173</ref>。「イナンナとエビフ([http://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/section1/tr132.htm%201.3.2 ETCSL 1.3.2])」、別名「恐るべき神通力の女神」は、アッカドの詩人エンヘドゥアンナが、イナンナとザグロス山脈のエビフ山との対決を描いた184行詩である<ref>Pryke, 2017, page165</ref>。この詩は、イナンナを讃える賛美歌の導入部から始まる<ref>Attinger, 1988, pages164–195</ref>。イナンナは世界中を旅していたが、エビフ山に出会い、その輝かしい力と自然の美しさに激怒し<ref>Karahashi, 2004, page111</ref>、その存在そのものを自分の権威に対する侮辱と考えるようになる<ref>Kramer, 1961, pages82–83</ref><ref>Pryke, 2017, page165</ref>。イナンナはエビフ山を怒鳴りつけ、叫んだ。 | |

| − | + | <blockquote> | |

| + | 山は、標高が高いから、身長が高いから。<br /> | ||

| + | あなたの優しさのせいで、あなたの美しさのせいで。<br /> | ||

| + | 聖なる衣を身にまとったせいで。<br /> | ||

| + | アンがあなたを整えた(?)せいで。<br /> | ||

| + | あなたが(その)鼻を地面に近づけなかったせいで。<br /> | ||

| + | 唇を塵に押しつけなかったせいで<ref>Karahashi, 2004, pages111–118</ref>。 | ||

| + | </blockquote> | ||

| − | + | イナンナはシュメールの天の神アンに、エビフ山を破壊することを許すよう懇願した<ref>Karahashi, 2004, page111</ref>。アンはイナンナに山を攻撃しないように警告するが<ref>Karahashi, 2004, page111</ref>、イナンナは彼の警告を無視してエビフ山を攻撃し破壊してしまう<ref>Karahashi, 2004, page111</ref>。神話の結末で、彼女はエビフ山をなぜ攻撃したかを説明する<ref>Karahashi, 2004, pages111–118</ref>。シュメールの詩では、イナンナの諡号の一つに「クルの破壊者」というフレーズが使われることがある<ref>Kramer, 1961, page82</ref>。 | |

| − | + | 「イナンナとシュカレトゥダの詩([http://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/section1/tr133.htm%201.3.3 ETCSL 1.3.3])」は、イナンナを金星として讃える賛美歌から始まる<ref>Cooley, 2008, page162</ref>。そして、仕事が苦手な庭師のシュカレツダが紹介される。1本のポプラの木を除いて、植物はすべて枯れてしまった<ref>Cooley, 2008, page162</ref>。シュカレトゥダは神々に仕事の導きを祈る。驚いたことに、女神イナンナは彼の一本のポプラの木を見て、その枝の陰で休むことにした<ref>Cooley, 2008, page162</ref>。シュカレトゥダはイナンナが寝ている間に服を脱がせ、犯す<ref>Cooley, 2008, page162</ref>。目を覚ました女神は、自分が犯されたことを知り、激怒し、犯人を裁こうと決意する<ref>Cooley, 2008, page162</ref>。イナンナは怒りにまかせて、水を血に変えるという恐ろしい災いを地上に放った<ref>Cooley, 2008, page162</ref>。シュカレトゥダは身の危険を感じ、父にイナンナの怒りから逃れる方法を懇願する<ref>Cooley, 2008, page162</ref>。シュカレトゥダは父に言われ、街の中に隠れ、人の群れに紛れ込んだ<ref>Cooley, 2008, page162</ref>。イナンナは自分を襲った相手を東方の山々で探したが<ref>Cooley, 2008, page162</ref>、見つけることはできなかった<ref>Cooley, 2008, page162</ref>。その後、彼女は一連の嵐を放ち、都市への道をすべて閉じたが、それでもシュカレトゥダを見つけることができず<ref>Cooley, 2008, page162</ref>、エンキに彼を見つける手助けを求め、そうしなければウルクの神殿から離れると脅迫した<ref>Cooley, 2008, page162</ref>。エンキは承諾し、イナンナは「虹のように空を横切って飛んだ」<ref>Cooley, 2008, page162</ref>。イナンナはついにシュカレトゥダの居場所を突き止めたが、シュカレトゥダは自分に対する罪の言い訳を必死に考えていた。イナンナは言い訳を拒否し、シュカレトゥダを殺してしまう<ref>Cooley, 2008, page163</ref>。神学者のジェフリー・クーリーは、シュカレトゥダの物語をシュメールの星辰神話として引用し、物語の中のイナンナの動きが金星の動きと対応していると論じている<ref>Cooley, 2008, pages161–172</ref>。また、シュカレトゥダが女神に祈りを捧げている間、地平線上にある金星の方を見ていたのではないかとも述べている<ref>Cooley, 2008, page163</ref><ref group="私注">これは広く「眠り姫」系の民間伝承と同じ系統の話と思われる。子供ができて、子供が自ら父親を明かす、という定型的な物語なのだが(日本で言うところの「丹塗りの矢」である。)イナンナの神話の方が変形版と言うべきで、イナンナの苛烈な性格が現されているように思う。</ref>。 | |

| − | [ | + | ニップルで発見された詩『イナンナとビルル』([http://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/section1/tr144.htm%201.4.4 ETCSL 1.4.4])のテキストはひどく破損しており<ref>Leick, 1998, page89</ref>、学者たちはこれをさまざまに解釈している<ref>Leick, 1998, page89</ref>。詩の冒頭はほとんど破壊されているが<ref>Leick, 1998, page=89</ref>、哀歌のようである<ref>Leick, 1998, page89</ref>。この詩の理解しやすい部分は、イナンナが、草原で群れを見守る夫ドゥムジに恋い焦がれる様子を描いている<ref>Leick, 1998, page89</ref><ref>Fontenrose, 1980, page165</ref>。イナンナは彼を探す旅に出る<ref>Leick, 1998, page89</ref>。この後、本文の大部分が欠落する<ref>Leick, 1998, page89</ref>。物語が再開されると、イナンナはドゥムジッドが殺されたことを告げられる<ref>Leick, 1998, page89</ref>。イナンナは、盗賊の老婆ビルルとその息子ギルギレが犯人であることを突き止めます<ref>Pryke, 2017, page166</ref><ref>Fontenrose, 1980, page165</ref>。彼女はエデンリラへの道を進み、宿に立ち寄ると、そこで二人の殺人犯を発見する<ref>Leick, 1998, page89</ref>。イナンナは椅子の上に立ち<ref>Leick, 1998, page89</ref>、ビルルを「砂漠で人が運ぶ水瓶」に変え<ref>Leick, 1998, p89, Black Green, 1992, p109, Pryke, 2017, p166, Fontenrose, 1980, p165</ref>、ドゥムジッドの葬儀のための酒を注ぐことを強要する<ref>Leick, 1998, page89</ref><ref>Fontenrose, 1980, page165</ref>。 |

| − | + | == 冥界への降下 == | |

| + | イナンナ/イシュタルの冥界への降臨の物語には、ウル第三王朝(前2112年頃 - 前2004年)のシュメール語版([http://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/section1/tr141.htm%201.4.1 ETCSL 1.4.1])<ref>Kramer, 1961, pages83–86</ref><ref>Wolkstein, Kramer, 1983, pages127–135</ref><ref>Kramer, 1961, pages83–86</ref><ref>Wolkstein, Kramer, 1983, pages127–135</ref>と前2千年初頭<ref>Kramer, 1961, pages83–86</ref><ref>Wolkstein, Kramer, 1983, pages127–135</ref>に派生したことが明らかなアッカド語版の2種類のバージョンが残っている<ref>Brandão, 2019, アッカド語の詩がシュメール語の詩を要約あるいは歪曲したに過ぎないという意見には反対であるが、相互文通の関係には疑問の余地はない。, pp19, 65–67</ref>。シュメール語版の物語は、後のアッカド語版の3倍近い長さがあり、より詳細な内容が含まれている<ref>Dalley, 1989, page154</ref>。 | ||

| − | + | === シュメール語版 === | |

| + | シュメールの宗教では、クルは地下深くにある暗く寂しい洞窟として考えられていた<ref>Choksi, 2014</ref>。そこでの生活は「地上での生活の影のようなもの」として想定されていた<ref>Choksi, 2014</ref>。 クルはイナンナの姉である女神エレシュキガルが支配していた<ref>Black, Green, 1992, page77</ref><ref>Choksi, 2014</ref>。イナンナは出発する前に、彼女の大臣兼召使いのニンシュブルに、3日経っても戻ってこない場合は、エンリル、ナンナ、アン、エンキの神々に救出を懇願するように指示した<ref>Kramer, 1961, pages86–87</ref><ref>Penglase, 1994, page17</ref>。冥界の掟では、任命された使者を除いて、そこに入った者は決して外に出ることができない<ref>Kramer, 1961, pages86–87</ref>。イナンナは、ターバン、かつら、ラピスラズリのネックレス、胸にビーズ、パラドレス(淑女の衣装)、マスカラ、胸飾り、金の指輪を身につけ、ラピスラズリの物差しを持って訪問した<ref>Kramer, 1961, page88</ref><ref>Wolkstein, Kramer, 1983, page56</ref>。それぞれの衣服は、彼女の持つパワフルなメーを表現している<ref>Wolkstein, Kramer, 1983, page157</ref>。 | ||

| − | + | イナンナは冥界の門を叩いて、入れてくれるように要求した<ref>Kramer, 1961, page90</ref><ref>Wolkstein, Kramer, 1983, pages54–55</ref><ref>Penglase, 1994, page17</ref>。門番のネティが「なぜ来たのか」と問うと<ref>Black, Green, 1992, page77</ref><ref>Kramer, 1961, page90</ref><ref>Wolkstein, Kramer, 1983, page55</ref>、イナンナは「姉エレシュキガルの夫」グガランナの葬儀に参列したいのだと答える<ref>Kramer, 1961, page91</ref><ref>Wolkstein, Kramer, 1983, pages56–57</ref>。ネティはこのことをエレシュキガルに報告し、エレシュキガルはこう告げた。「冥界の7つの門に閂をかけよ。そして、1つ1つゲートを開けて、イナンナを入れなさい。彼女が入ったら、王家の衣を脱がせるように<ref>Wolkstein, Kramer, 1983, page57</ref>。」おそらく、イナンナの衣服が葬儀にふさわしくないことと、イナンナの高慢な振る舞いを見て、エレシュキガルが不審に思ったのだろう<ref>Kilmer, 1971, pages299–309</ref>。エレシュキガルの指示に従い、ネティはイナンナに冥界の第一門に入ってよいが、ラピスラズリの物差しを渡さなければならないと告げた。イナンナがその理由を尋ねると、"地下世界の常識だ "と言われた。イナンナはそれに応え、通過した。イナンナは合計7つの門をくぐり、それぞれの門で旅の始まりに着ていた衣服や宝石を取り去り<ref>Kramer, 1961, page87</ref>、力を奪われていった<ref>Wolkstein, Kramer, 1983, pages157–159</ref><ref>Penglase, 1994, page17</ref>。姉の前に現れた彼女は、全裸であった<ref>Wolkstein, Kramer, 1983, pages157–159</ref><ref>Penglase, 1994, page17</ref>。 | |

| − | |||

| − | + | <blockquote>しゃがみこんで服を脱がされた後、イナンナは運ばれていく。そして、姉のエレシュキガルをその座から立たせ、代わりに自分が座に座った。7人の審判者であるアンナは、彼女に対して決定を下した。彼らは彼女を見た。それは死の目だった。彼らは彼女に話しかけた。それは怒りの言葉だった。彼らは彼女に向かって叫んだ--それは重い罪の意識の叫びであった。悩める女性は死体となってしまった。そして、その死体はフックに吊るされた<ref>Black Jeremy, Cunningham Graham, Flückiger-Hawker Esther, Robson Eleanor, Taylor John, Zólyomi Gábor, Inana's descent to the netherworld, http://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/section1/tr141.htm, Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature, Oxford University, 22 June 2017</ref>。</blockquote> | |

| − | + | 三日三晩が過ぎ、ニンシュブルは指示に従って、エンリル、ナンナ、アン、エンキの神殿を訪れ、それぞれにイナンナ救出を懇願した<ref>Kramer, 1961, pages93–94</ref><ref>Wolkstein, Kramer, 1983, pages61–64</ref><ref>Penglase, 1994, pages17–18</ref>。最初の三神はイナンナの運命は自分のせいだと言って断るが,<ref>Kramer, 1961, pages93–94</ref><ref>Wolkstein, Kramer, 1983, pages61–62</ref><ref>Penglase, 1994, page18</ref>、エンキは深く悩み、助けることに同意する<ref>Kramer, 1961, page94</ref><ref>Wolkstein, Kramer, 1983, pages62–63</ref><ref>Penglase, 1994, page18</ref>。彼は、2本の指の爪の下の汚れから、ガラトゥーラとクルジャラという名の2つの性別のない人物を作り出した<ref>Kramer, 1961, page94</ref><ref>Wolkstein, Kramer, 1983, page64</ref><ref>Penglase, 1994, page18</ref>。エンキはエレシュキガル<ref>Kramer, 1961, page94</ref><ref>Wolkstein, Kramer, 1983, page64</ref>を鎮め、彼女が望みを尋ねたらイナンナの死体を要求し、生命の食物と水を振りかけなければならない、と指示した<ref>Kramer, 1961, page94</ref><ref>Wolkstein, Kramer, 1983, page64</ref>。彼らがエレシュキガルの前に現れると、エレシュキガルはまるで出産する女性のように苦悶の表情を浮かべた<ref>Wolkstein, Kramer, 1983, pages65–66</ref>。エレシュキガルは、生命を与える水の川や穀物の畑など、欲しいものは何でも差し出したい、と述べたが<ref>Wolkstein, Kramer, 1983, page65</ref>、彼らはその申し出をすべて断り、イナンナの死体だけを要求した<ref>Wolkstein, Kramer, 1983, pages65–66</ref>。ガラトゥーラとクルジャラはイナンナの亡骸に生命の糧と水を与え、蘇生させた<ref>Kramer, 1961, pages94–95</ref><ref>Wolkstein, Kramer, 1983, pages67–68</ref><ref>Penglase, 1994, page18</ref>。エレシュキガルが送り込んだガラの魔物たちは、イナンナの代わりに誰かを冥界に連れて行くべきだと主張し、イナンナを冥界から追い出した<ref>Kramer, 1961, page95</ref><ref>Wolkstein, Kramer, 1983, pages68–69</ref><ref>Penglase, 1994, page18</ref>。彼らはまずニンシュブルに会い、彼女を連れ去ろうとするが<ref>Kramer, 1961, page=95</ref><ref>Wolkstein, Kramer, 1983, pages68–69</ref><ref>Penglase, 1994, page18</ref>、イナンナはニンシュブルは彼女の忠実な下僕であり、彼女が冥界にいる間は当然彼女を弔ったと主張して彼らを止めた<ref>Kramer, 1961, page95</ref><ref>Wolkstein, Kramer, 1983, pages68–69</ref><ref>Penglase, 1994, page18</ref>。そして、イナンナの執事であるシャラに出会った。彼はまだ喪に服していた<ref>Kramer, 1961, pages95–96</ref><ref>Wolkstein, Kramer, 1983, pages69–70</ref><ref>Penglase, 1994, page18</ref>。悪魔は彼を連れて行こうとするが、イナンナは、彼もまた彼女のために嘆いたのだから、連れて行くなと主張した<ref>Kramer, 1961, page96</ref><ref>Wolkstein, Kramer, 1983, pages70</ref><ref>Penglase, 1994, page18</ref>。3人目に出会ったのは、やはり喪服姿のルラルだった<ref>Kramer, 1961, page96</ref><ref>Wolkstein, Kramer, 1983, pages70–71</ref><ref>Penglase, 1994, page18</ref>。魔物たちは彼を連れ去ろうとするが、イナンナは再びそれを阻止した<ref>Kramer, 1961, page96</ref><ref>Wolkstein, Kramer, 1983, pages70–71</ref><ref>Penglase, 1994, page18</ref>。 | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | そして、ついにイナンナの夫であるドゥムジに出会う<ref>Wolkstein, Kramer, 1983, pages71–73</ref><ref>Penglase, 1994, page18</ref>。イナンナの運命とは裏腹に、彼女をきちんと弔っていた他の人々とは対照的に、ドゥムジは豪華な服を着て、木の下や玉座で休み、奴隷の少女にもてなされていた。イナンナは不愉快に思い、ガラに彼を連れて行くように命じた<ref>Wolkstein, Kramer, 1983, |pages71–73</ref><ref>Penglase, 1994, page18</ref><ref>Tinney, 2018, page86</ref>。そして、ガラはドゥムジを冥界に引きずり込んだ<ref>Wolkstein, Kramer, 1983, pages71–73</ref><ref>Penglase, 1994, page18</ref>。「ドゥムジの夢」([http://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/section1/tr143.htm%201.4.3 ETCSL 1.4.3])には、ドゥムジが太陽神ウトゥに助けられて、ガラの魔物に捕まらないよう何度も試みる様子が描かれている<ref>Tinney, 2018, pages85–86</ref><ref>Wolkstein, Kramer, 1983, pages74–84</ref><ref>「ドゥムジの夢」は、ニップルから55点、ウルから9点、シッパール周辺から3点、ウルク、キシュ、シャドゥプム、スーサから各1点の計75点の資料で確認されている。(Tinney, 2018, page86)</ref> | |

| + | 。『ドゥムジッドの夢』が終わったところから始まるシュメール詩『ドゥムジッドの帰還』では、ドゥムジの妹ゲシュティナンナが、心変わりしたらしいイナンナとドゥムジの母シルトゥールとともにドゥムジの死を昼夜問わず嘆き続ける<ref>Wolkstein, Kramer, 1983, pages85–87</ref>。三人の女神は悲しみに暮れるが、一匹のハエがイナンナに夫の居場所を教える<ref>Wolkstein, Kramer, 1983, pages87–89</ref>。イナンナとゲシュティナンナは一緒に、ハエがドゥムジに出会えると告げた場所に行く<ref>Wolkstein, Kramer, 1983, pages88–89</ref>。そして、イナンナはドゥムジに、1年の半分を姉のエレシュキガルと共に冥界で、残りの半分を姉と共に天界で過ごすように命じ、姉のゲシュティナンナが彼の代わりに冥界に赴くことにした<ref>Kramer, 1966, page31</ref><ref>Penglase, 1994, page18</ref><ref>Wolkstein, Kramer, 1983, pages85–89</ref>。 | ||

| − | + | === アッカド語版 === | |

| + | この版には、アッシュールバニパル図書館で見つかった2つの写本と、アッシュールで見つかった3つの写本があり、いずれも共通時代以前の1千年紀の前半に作られたものである<ref>Brandão, 2019, p11</ref>。ニネヴィット語版のうち、最初の楔形文字版は1873年にフランソワ・ルノルマンによって、音訳版は1901年にピーター・イェンセンによって出版された<ref>Brandão, 2019, p11</ref>。アッカド語のタイトルは「Ana Kurnugê, qaqqari la târi」である<ref>Brandão, 2019, p11</ref>。 | ||

| − | + | アッカド語版では、イシュタルが冥界の門に近づき、門番に自分を入れてくれるよう要求するところから始まる。 | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | <blockquote>もし私が入るために門を開けないのなら、<br /> | |

| + | 扉を壊し、閂を打ち砕くだろう。<br /> | ||

| + | わたしは門柱を打ち砕き、戸をひっくり返そう。<br /> | ||

| + | わたしは死者をよみがえらせ、生者を食べさせる。<br /> | ||

| + | 死者は生者を凌駕することになる<ref>Dalley, 1989, page155</ref><ref>Brandão, 2019, p13</ref>。</blockquote> | ||

| − | + | 門番(アッカド語版では名前は不明<ref>Dalley, 1989, page155</ref>)は急いでエレシュキガルにイシュタルの到着を伝える。エレシュキガルは、イシュタルを中に入れるよう命じるが、「古代の儀式に従って彼女を扱うように」と告げる<ref>Dalley, 1989, page156</ref>。門番はイシュタルを冥界に入れ、門を一つずつ開けていく<ref>Dalley, 1989, page156</ref>。各ゲートで、イシュタルは服を一枚脱ぐことを強いられる。ようやく7つ目の門をくぐったときには、彼女は裸になっていた<ref>Dalley, 1989, pages156–157</ref>。怒ったイシュタルはエレシュキガルに殴りかかるが、エレシュキガルは召使いのナムタルに命じてイシュタルを幽閉し、60の病を解き放った<ref>Dalley, 1989, page157-158</ref>。 | |

| − | + | イシュタルが冥界に降りた後、地上ではすべての性行為が停止された<ref>Dalley, 1989, pages158–160</ref><ref>Brandão, 2019, pp15-16</ref>。アッカド語のニンシュブルに相当するパプスカル神<ref>Bertman, 2003, page124</ref>は、知恵と文化の神エアに状況を報告する<ref>Dalley, 1989, pages158–160</ref>。エアはアス・シュ・ナミール(Asu-shu-namir)という両性具有の存在を作り、エレシュキガルのもとに送り、彼女に対して「偉大なる神々の名」を唱え、命の水の入った袋を要求するようにと言った。アス・シュ・ナミールはこの水をイシュタルに振りかけ、彼女を蘇らせた。その後、イシュタルは7つの門をくぐり、それぞれの門で1着ずつ服を返してもらい、最後の門から完全に服を着て出てくる<ref>Dalley, 1989, pages158–160</ref>。 | |

| − | === | + | === 現代アッシリア学における解釈 === |

| − | + | シュメールの死後の世界の信仰と葬儀の習慣の権威であるディーナ・カッツは、イナンナの降臨の物語は、メソポタミアの宗教の広い文脈に根ざした、二つの異なる既存の伝統の組み合わせであるとみなしている。 | |

| − | + | ある伝承では、イナンナはエンキの術によってのみ冥界を去ることができたとされ、身代わりを見つける可能性については言及されていない<ref>Katz, 2015, p65</ref>。この部分は、権力や栄光などを得るために苦闘する神々を描いた神話(『ルガルエ』や『エヌマ・エリシュ』など)のジャンルに属し<ref>Katz, 2015, p65</ref>、周期的に消滅する星霊体の擬人化としてのイナンナの性格を表現する役割を果たした可能性もある<ref>Katz, 2015, p66</ref>。カッツによれば、イナンナのニンシュブルに対する指示には、彼女を救出する手段も含めて、最終的な運命が正確に予言されていることから、この神話の目的は、イナンナが天界と地下世界の両方を行き来できる能力を強調することに他ならず、あたかも金星が何度も復活するのと同じことだという<ref>Katz, 2015, p66</ref>。 | |

| − | + | もう一つは、イナンナの神話はドゥムジの死に関する多くの神話(『ドゥムジの夢』や『イナナとビルル』など、これらの神話ではイナンナは彼の死について非難していない)の一つに過ぎず、植生の体現者としての彼の役割と結びついたものである<ref>Katz, 2015, p68</ref>。彼女は、物語の2つの部分のつながりは、再生される人の象徴的な身代わりを必要とする、よく知られた再生の儀式を反映したものである可能性を考えている<ref>Katz, 2015, p67-68</ref>。 | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | またカッツは、シュメール版の神話は豊穣の問題には触れておらず、豊穣に関する言及(例えばイシュタルが死んでいる間は自然は不妊である)は、後のアッカド語訳においてのみ加えられたと指摘している<ref>Katz, 2015, p70</ref><ref>Katz, 2015, p70</ref>。このような変更は、神話を、タンムーズの死を毎年悼み、その後、一時的な復活を祝うという、タンムーズに関連する崇拝の伝統に近づけるためであったと思われる<ref>Katz, 2015, p70-71</ref>。カッツによれば、アシュールやニネベなど、タンムズ崇拝で知られるアッシリアの都市から、後世の神話の多くの複製が出土していることは注目に値するという<ref>Katz, 2015, p70</ref>。 | |

| − | + | === その他の解釈 === | |

| + | 20世紀には、アッシリア学というよりユング分析の伝統に根ざした、あまり学術的でない神話の解釈が数多く生まれた。また、ギリシャ神話のペルセポネ拉致事件と比較する著者もいる<ref>Dobson, 1992</ref>。 | ||

| − | + | モニカ・オッターマンは神話のフェミニスト的解釈を行い、自然のサイクルに関連した解釈を疑問視し<ref>Brandão, 2019, p71</ref>、物語がイナンナの力がメソポタミアの家父長制によって制限されていたことを表していると主張し、彼女によれば、この地域は豊穣をもたらすものではなかったという<ref>Brandão, 2019, p72</ref>。シュメール語のテキストではイナンナの力が問題になっているが、アッカド語のテキストでは女神と豊穣や受精との関係が問題になっているからである。さらにシュメール語では、イナンナの力を制限するのは男性ではなく、同じく力のあるもう一人の女神エレシュキガルである<ref>Brandão, 2019, p72</ref>。 | |

| − | + | == 後の神話 == | |

| + | === ''ギルガメシュ叙事詩'' === | ||

| + | アッカド語の『ギルガメシュ叙事詩』では、鬼のフンババを倒してウルクに戻ったギルガメシュと仲間のエンキドゥの前にイシュタルが現れ、ギルガメシュに配偶者になることを要求する<ref>Dalley, 1989, page80</ref><ref>アブシュは、イシュタルの提案はギルガメッシュが死者の世界の労働者となることであるというテーゼを提案する。(Brandão、2019、p59)</ref> 。ギルガメシュは、これまでの恋人がみな苦しんでいたことを指摘し、彼女を拒絶する<ref>Dalley, 1989, page80</ref>。 | ||

| − | + | <blockquote> | |

| + | お前の恋人の物語を話すから聞くように。タンムズはお前の青春の恋人だった。彼のためにお前は毎年、慟哭の令を出した。お前は色とりどりのライラック・ブレスト・ローラーを愛していたが、それでもお前はその翼を打ち、折ってしまった[...]。お前は力のとてつもない獅子を愛した。だが、彼のために七つの穴を掘った。お前は戦場で立派な種馬を愛した。だが、彼のために鞭と拍車と紐を定めた [...]。お前は羊の群れの羊飼いを愛した。彼は毎日お前のために食事を作り、お前のために子供を殺した。お前は彼を殴って狼に変えた。今、彼の群れの少年たちは彼を追い払い、彼の猟犬は彼の脇腹を狙う<ref name="Gilgamesh' p. 86">''Gilgamesh'', p. 86</ref>。</blockquote> | ||

| − | + | ギルガメシュの拒絶に激怒したイシュタルは<ref>Dalley, 1989, page80</ref>、天界に行き、父アヌにギルガメシュが自分を侮辱したことを告げる<ref>Dalley,1989, page80</ref>。アヌは、なぜ自分でギルガメッシュに立ち向かわず、彼に文句を言うのかと問う<ref>Dalley, 1989, page80</ref>。イシュタルはアヌに「天の雄牛」を要求し<ref>Dalley, 1989, page80</ref>、もし与えなければ「地獄の扉を破って閂を打ち破り、人々の混乱(=混合)が起こるだろう、上の者たちと下の者たちとが。私は死者を蘇らせて、生者と同じように食物を食べさせ、死者の軍勢は生者を凌駕することになる。」と誓った<ref>''Gilgamesh'', p. 87</ref>。 | |

| − | |||

| − | + | アヌはイシュタルに天の雄牛を与え、イシュタルはそれを送ってギルガメシュとその友人エンキドゥを攻撃させた<ref>Dalley, 1989, pages81–82</ref><ref>Fontenrose, 1980, pages168–169</ref>。ギルガメシュとエンキドゥは牡牛を殺し、その心臓を太陽神シャマシュに捧げた<ref>Dalley, 1989, page82</ref><ref>Fontenrose, 1980, pages168–169</ref>。ギルガメシュとエンキドゥが休んでいる間、イシュタルがウルクの城壁に立ち、ギルガメシュを呪った<ref>Dalley, 1989, page82</ref><ref>Fontenrose, 1980, page169</ref>。エンキドゥは牡牛の右腿を引きちぎってイシュタルの顔に投げつけ<ref>Dalley, 1989, page82</ref><ref>Fontenrose, 1980, page169</ref>、「もし私があなたに手をかけることができるなら、あなたにこうして、あなたの内臓をあなたの横になでつけるべきでしょう。」と言う<ref name="Gilgamesh-p88">''Gilgamesh'', p. 88</ref><ref group="私注">牛の右腿は古代エジプトでは神に捧げ得る最善の供物であったように記憶している。</ref>。(エンキドゥはこの不敬のために、後に死ぬ<ref>Fontenrose, 1980, page169</ref>。)イシュタルは「ひだのある花魁、娼婦、遊女」<ref>Dalley, 1989, page82</ref>を呼び集め、天の雄牛のために嘆き悲しむよう命じる<ref>Dalley, 1989, page82</ref><ref>Fontenrose, 1980, page169</ref>。一方、ギルガメッシュは天の牡牛を倒す祝宴を開いた<ref>Dalley, 1989, page82-83</ref><ref>Fontenrose, 1980, page169</ref>。 | |

| − | + | 叙事詩の後半、ウトナピシュティムはギルガメシュに大洪水の話をする<ref>Dalley, 1989, pages109–116</ref>。大洪水は、人口が膨大に増えた人間が騒ぎすぎて眠れなくなったため、エンリル神が地球上のすべての生命を消滅させるために送ったものである<ref>Dalley, 1989, pages109–111</ref>。ウトナピシュティムは、洪水が来たとき、イシュタルがアヌンナキと一緒に人類の滅亡を嘆き悲しんだことを伝えている<ref>Dalley, 1989, page113</ref>。その後、洪水が収まった後、ウトナピシュティムは神々に捧げものをした<ref>Dalley, 1989, page114</ref>。イシュタルは、ハエの形をした瑠璃色の首飾りをつけてウトナピシュティムの前に現れ、エンリルが他の神々と洪水について話し合ったことはないと告げた<ref>Dalley, 1989, pages114–115</ref>。彼女はエンリルが再び洪水を起こすことを決して許さないと彼に誓い<ref>Dalley, 1989, pages114–115</ref>、瑠璃色の首飾りを誓いの証として宣言した<ref>Dalley, 1989, pages114–115</ref>。イシュタルは、エンリルを除くすべての神々を招き、供物を囲んで楽しんだ<ref>Dalley, 1989, page115</ref>。 | |

| − | + | === ''アグシャヤの歌'' === | |

| + | 『アグシャヤの歌』<ref>Foster, Benjamin R. (2005<sup>3</sup>), Before the Muses. An Anthology of Akkadian Literature, Bethesda, pp. 96-106. | ||

| − | + | SEAL: [https://seal.huji.ac.il/node/7493?tid=114 VS 10, 214 (Agušaya A)] | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | SEAL: [https://seal.huji.ac.il/node/7494?tid=114 RA 15, 159ff. (Agušaya B)]</ref>は、ハンムラビの時代のものと推定されるアッカド語のテキストで、戦争女神イシュタルが絶え間ない怒りに満たされ、戦争と戦いで地上を苦しめるという、賛美歌の一節を交えた神話を語っている。その咆哮は、ついにアプスーにいる賢神エアをも脅かす。彼は神々の集会に現れ、(ギルガメシュ叙事詩のエンキドゥと同様に)イシュタルと対等に戦える相手を作ることを決意する。エアはその爪の汚れから、強力な女神サルタム(Ṣaltum(「戦い、喧嘩」))を作り、イシュタルに不遜な態度で立ち向かい、昼夜問わずその咆哮で彼女を苦しめるように指示した。両女神が対峙するテキスト部分は残されていないが、その後にイシュタルがエアにサルタムを呼び戻すように要求し、エアがそれを実行する場面がある。その後、エアはこの出来事を記念して、以後毎年「渦巻き踊り」(gūštû)を踊る祭りを創設する。そして、イシュタルの心が落ち着いたという言葉で、本文は終わる。 | |

| − | == | + | === その他の物語 === |

| − | + | シャマシュの息子とされるイシュム神の幼少期を描いた神話では、イシュタルが一時的に彼の世話をしたようで、その状況に苛立ちを感じている様子が描かれている<ref>George, 2015, p7-8</ref>。 | |

| − | |||

| − | + | 前7世紀に書かれた新アッシリアの偽典で、アッカドのサルゴンの自伝と主張するものでは<ref>Westenholz, 1997, pages33–49</ref>、イシュタルはサルゴンが水の引き出し主であるアッキの庭師として働いているときに「鳩の雲に包まれて」現れたと主張されている<ref>Westenholz, 1997, pages33–49</ref>。イシュタルはサルゴンを自分の恋人と宣言し、シュメールとアッカドの支配者になることを許した<ref>Westenholz, 1997, pages33–49</ref>。 | |

| − | + | ヒッタイト語のテキストでは、<sup>d</sup>ISHTARという記号が女神シャウシュカを表し、神名帳などでもイシュタルと同一視され、後期アッシリアのニネヴェのイシュタル信仰に影響を与えたとヒッタイト学者ゲイリー・ベックマンは述べている<ref>Beckman, 1998, p1-3</ref>。シャウッシュカはクマルビ・サイクルのフルリ神話では重要な役割を担っている<ref>Hoffner, 1998, p41</ref>。 | |

| − | + | == 後の影響 == | |

| + | === 古代において === | ||

| + | イナンナ/イシュタル信仰はマナセ王の時代にユダ王国に伝わったと考えられ<ref>Pryke, 2017, page193</ref>、イナンナ自身の名前は聖書に直接出てこないものの<ref>Pryke, 2017, pages193, 195</ref>、旧約聖書には彼女の信仰に関する多くの暗示が含まれている<ref>Pryke, 2017, pages193–195</ref>。エレミヤ書7:18とエレミヤ書44:15-19には「天の女王」が登場するが、これはおそらくイナンナ/イシュタルと西セム語の女神アスタルテが習合したものであろう<ref>Pryke, 2017, page193</ref><ref>Breitenberger, 2007, page10</ref><ref>Smith, 2002, page182</ref><ref>Ackerman, 2006, pages116–117</ref>。エレミヤ書によると、天の女王は、彼女のためにケーキを焼く女性たちによって崇拝されていた<ref>Ackerman, 2006, pages115–116</ref>。 | ||

| − | + | 『歌の歌』はシュメールのイナンナとドゥムジの恋愛詩と強い類似性を持っており<ref>Pryke, 2017, page194</ref>、特に恋人たちの身体性を表すために自然の象徴が用いられている<ref>Pryke, 2017, page194</ref>。歌の歌6:10 エゼキエル書8:14には、イナンナの夫ドゥムジが後の東セム語名であるタンムズで言及されており<ref>Black, Green, 1992, page73</ref><ref>Pryke, 2017, page195</ref><ref>Warner, 2016, page211</ref>、エルサレムの神殿北門近くに座ってタンムズの死を嘆く女たちの一団が描かれている<ref>Pryke, 2017, page195</ref><ref>Warner, 2016, page211</ref>。マリナ・ワーナー(アッシリア学者ではなく文芸評論家)は、中東の初期キリスト教徒がイシュタルの要素を聖母マリアの信仰に同化させたと主張している<ref>Warner, 2016, pages210–212</ref>。彼女は、シリアの作家であるセルグのヤコブとメロディストのロマノスが書いた哀歌の中で、聖母マリアが十字架の下にいる息子への憐れみを、イシュタルのタンムズの死に対する哀歌によく似た、深く個人的な言葉で表現していると論じている<ref>Warner, 2016, page212</ref>。しかし、タンムズと他の瀕死の神々との幅広い比較は、ジェームズ・ジョージ・フレイザーの仕事に根ざしており、最近の出版物では、より厳密でない20世紀初頭のアッシリ学の遺物と見なされている<ref>Alster, 2013, p433-434</ref>。 | |

| − | + | イナンナ/イシュタルの信仰は、フェニキアの女神アスタルテの信仰にも大きな影響を与えた<ref>Marcovich, 1996, pages43–59</ref>。フェニキア人はアスタルテをギリシャのキプロス島とキティラ島に伝え<ref>Breitenberger, 2007, page10</ref><ref>Cyrino, 2010, pages49–5</ref>、そこでギリシャの女神アプロディーテを生み出したか、大きな影響を及ぼした<ref>Breitenberger, 2007, pages8–12</ref><ref>Cyrino, 2010, pages49–52</ref><ref>Puhvel, 1987, page27</ref><ref>Marcovich, 1996, pages43–59</ref>。アプロディーテはイナンナ/イシュタルの性愛と子孫繁栄のイメージを受け継いだ<ref>Breitenberger, 2007, page8</ref><ref>Penglase, 1994, page162</ref>。さらに、アプロディーテはは「天上の」という意味のウラーニア(Οὐρανία)と呼ばれ<ref>Breitenberger, 2007, pages10–11</ref><ref>Penglase, 1994, page162</ref>、イナンナの天国の女王としての役割に相当する称号であった<ref>Breitenberger, 2007, pages10–11</ref><ref>Penglase, 1994, page162</ref>。 | |

| − | + | 初期の芸術や文学で描かれたアプロディーテは、イナンナ/イシュタルと極めてよく似ている<ref>Breitenberger, 2007, page8</ref><ref>Penglase, 1994, page162</ref>。アプロディーテは戦士の女神でもあった<ref>Breitenberger, 2007, page8</ref><ref>Cyrino, 2010, pages49–52</ref><ref>Penglase, 1994, page163</ref>。紀元2世紀のギリシャの地理学者パウサニアスは、スパルタにおいて、アプロディーテは「戦士」を意味するアプロディーテ・アレイアとして崇拝されていたと記録している<ref>Cyrino, 2010, pages51–52</ref><ref>Budin, 2010, pages85–86, 96, 100, 102–103, 112, 123, 125</ref>。パウサニアスは、また、スパルタとキュテラ島の最も古いアプロディーテの彫像は、彼女が武器を持つ姿を示していたとも述べている.<ref>Cyrino, 2010, p51–52, Budin, 2010, p85–86, 96, 100, 102–103, 112, 123, 125, Graz, 1984, p250, Breitenberger, 2007, p8</ref>。最近の学者たちは、アプロディーテの戦士女神の側面が彼女の崇拝の最も古い層に現れていることに注目し<ref>Iossif, Lorber, 2007, page77</ref>、それを彼女の近東での起源を示すものとして見ている<ref>Iossif, Lorber, 2007, page77</ref><ref>Penglase, 1994, page163</ref>。アプロディーテはまた、イシュタルの鳩との結びつきを吸収し<ref>Lewis, Llewel, yn-Jones, 2018, page335</ref><ref>Penglase, 1994, page163</ref>、鳩は彼女だけに生け贄として捧げられた<ref>Penglase, 1994, page163</ref>。ギリシャ語で「鳩」を意味するのはperisteráであり<ref>Lewis, Llewel, yn-Jones, 2018, page335</ref><ref>Botterweck, Ringgren, 1990, page35</ref>、これはセム語のperaḥ Ištar(「イシュタルの鳥」の意)に由来すると思われる<ref>Botterweck, Ringgren, 1990, |page35</ref>。アプロディーテとアドーニスの神話は、イナンナとドゥムジの物語に由来している<ref>West, 1997, page57</ref><ref>Burkert, 1985, page177</ref>。 | |

| − | + | 古典学者のチャールズ・ペングレイスは、ギリシア神話の知恵と戦争の女神アテーナーが、イナンナの「恐ろしい戦士の女神」としての役割に似ていると書いている<ref>Penglase, 1994, page235</ref>。また、アテーナーが父ゼウスの首から生まれたのは、イナンナが冥界に降り立ち、そこから戻ってきたことに由来すると指摘する人もいる<ref>Penglase, 1994, pages233–325</ref>。しかし、ゲイリー・ベックマンが指摘するように、アテーナーの誕生とかなり直接的な類似点が、イナンナ神話ではなく、クマルビの頭蓋骨を外科的に分割してテシュブを誕生させるフルリ・クマルビ・サイクル<ref>Beckman, 2011, p29</ref>に見出される。 | |

| − | + | マンデーの宇宙論では、金星の名前のひとつは「スティラ(ʿStira)」で、これはイシュタルの名前に由来しているとのことである<ref name="Bhayro 2020">Bhayro Siam, Hellenistic Astronomy, Cosmology in Mandaean Texts, Brill, 2020-02-10, https://brill.com/view/book/edcoll/9789004400566/BP000051.xml, 2021-09-03, pages572–579, doi:10.1163/9789004400566_046, isbn:9789004400566, s2cid:213438712</ref>。 | |

| − | + | 人類学者ケヴィン・トゥイテは、グルジアの女神ダリ(Dali)もイナンナの影響を受けていると主張し<ref>Tuite, 2004, pages16–18</ref>、ダリとイナンナがともにモーニングスターと関連していたこと<ref>Tuite, 2004, page16</ref>、どちらも特徴的に裸で描かれていたこと<ref>Tuite, 2004, pages16–17</ref>、(ただしアッシリア学者は、メソポタミア美術の「裸婦」モチーフはほとんどの場合イシュタルではないと考えており<ref>Wiggermann, 1998, p49</ref>、最も安定して裸婦として描かれていたのはイシュタルとは関係のない天候の女神であるシャラだと指摘している<ref>Wiggermann, 1998, p51</ref>)、どちらも金の宝石に関連し<ref>Tuite, 2004, pages16–17</ref>、どちらも人間の男性を性的に捕食し<ref>Tuite, 2004, page17</ref>、どちらも人間や動物の豊穣と関連し<ref>Tuite, 2004, pages17–18</ref>(ただしアッシリア学者のディーナ・カッツは、豊穣への言及は少なくともいくつかのケースでイナンナ/イシュタルよりもドゥムジに関連している傾向が強いと指摘している<ref>Katz, 2015, p70-71</ref>、そしてどちらも性的な魅力があるが危険でもあるという両義性を持った女性であることに留意される<ref>Tuite, 2004, page18</ref>。 | |

| − | + | メソポタミアの伝統的な宗教は、紀元3世紀から5世紀にかけて、アッシリアの民族がキリスト教に改宗したことにより、徐々に衰退し始めた。しかし、イシュタルとタンムズの信仰は、上メソポタミアの一部で存続することができた<ref>Warner, 2016, page211</ref>。紀元10世紀、アラブの旅行者は、「現代のすべてのサバイ人、バビロニアの人々もハランの人々も、同じ名前の月に、特に女性たちが行う祭りで、今日までタンムズのことを嘆き、泣いている」と記した<ref>Warner, 2016, page211</ref>。 | |

| − | + | イスラム以前のアラビアでは、イナンナやイシュタルに関連する金星の神々を崇拝することが、イスラム時代に至るまで知られていた。アンティオキアのイサク(紀元406年)は、アラブ人がAl-Uzzaとしても知られ、多くの人が金星と見なしている「星」(kawkabta)を崇拝していたと述べている<ref>Healey, 2001, p114-119</ref>。イサクは、バルティスというアラビアの神についても言及しているが、ヤン・レツォによれば、これはイシュタルの別の呼び名であった可能性が高い<ref>Retsö, 2014, p604-605</ref>。イスラム教以前のアラビア語の碑文自体にも、アラートと呼ばれる神は金星の神であったようだ<ref>Al-Jallad, 2021, p569-571</ref>。イシュタルと同名の男神アタルは、その名前と「東洋と西洋」という諡号から、アラビアの金星神としても有力な候補者である<ref>Ayali-Darshan, 2014, p100-101</ref>。 | |

| − | |||

| − | + | === 現代的な関連性 === | |

| + | スコットランド自由教会のプロテスタント牧師であったアレキサンダー・ヒスロップは、1853年に出版した小冊子『二つのバビロン』で、ローマ・カトリックは実はバビロニアの異教を装っているという主張の一環として、現代英語のイースターはイシュタルに由来するはずだと、二つの単語の音韻が似ていることから誤って主張したのである<ref>Hislop, 1903, page103</ref><ref group="私注">この点についての管理人の考えは'''[[エオステレ]]'''参照のこと。そもそも、イナンナとイシュタルが言語的に同起源とは思えないのに、無理矢理習合させてしまったアッカドのサルゴンにも問題があると考える。</ref>。現代の学者たちは、ヒスロップの主張は誤りであり、バビロニアの宗教に対する誤った理解に基づいていると、一様に否定している<ref>Grabbe, 1997, page28</ref><ref>Brown, 1976, page268</ref><ref>D'Costa, 2013</ref>。それにもかかわらず、ヒスロップの本は福音主義プロテスタントの一部のグループの間でいまだに人気があり<ref>Grabbe, 1997, page28</ref>、その中で宣伝された考えは、特にインターネットを通じて、多くの人気のあるインターネット・ミームによって広く流布している<ref>D'Costa, 2013</ref>。 | ||

| − | + | イシュタルは、1884年にアメリカの弁護士兼実業家であるレオニダス・ル・チェンチ・ハミルトンが、最近翻訳された『ギルガメッシュ叙事詩』に緩く基づいて書いた長編詩『イシュタルとイズドゥバル』<ref>Ziolkowski, 2012, pages20–21</ref>に大きく登場した<ref>Ziolkowski, 2012, pages20–21</ref>。イシュタルとイズドゥバルは、『ギルガメシュ叙事詩』の約3000行を、48のカントにまとめた約6000行の韻文対句に拡張した<ref>Ziolkowski, 2012, page21</ref>。ハミルトンは、ほとんどの登場人物を大幅に変更し、オリジナルの叙事詩にはない全く新しいエピソードを導入した<ref>Ziolkowski, 2012, page21</ref>。エドワード・フィッツジェラルドの『オマール・ハイヤームのルバイヤート』やエドウィン・アーノルドの『アジアの光』から大きな影響を受け<ref>Ziolkowski, 2012, page21</ref>、ハミルトンの登場人物は、古代バビロニアというよりは19世紀のトルコ人のような服装をしている<ref>Ziolkowski, 2012, pages22–23</ref>。詩の中で、イズドゥバル(以前は「ギルガメシュ」と誤読されていた)はイシュタルと恋に落ちるが<ref>Ziolkowski, 2012, page22</ref>、その後イシュタルは「熱く穏やかな息と、震える姿で」彼を誘惑しようとし、イズドゥバルは彼女の誘いを拒否することになる<ref>Ziolkowski, 2012, page22</ref>。この本のいくつかの「コラム」は、イシュタルの冥界への降下についての説明に費やされている<ref>Ziolkowski, 2012, pages22–23</ref>。本書の結末では、神となったイズドゥバルは、天国でイシュタルと和解する<ref>Ziolkowski, 2012, page23</ref>。1887年、作曲家ヴァンサン・ダンディは、大英博物館にあるアッシリアの遺跡からインスピレーションを得て、「交響曲イシュタル、変奏曲シンフォニック」作品42を作曲した<ref>Pryke, 2017, page196</ref>。 | |

| − | + | イナンナは男性優位のシュメールのパンテオンに登場するが<ref>Pryke, 2017, pages196–197</ref>、並んで登場する男性の神々よりも強力ではないにしても、同じくらい強力であるため、現代のフェミニスト理論において重要な人物となった<ref>Pryke, 2017, pages196–197</ref>。シモーヌ・ド・ボーヴォワールは、著書『第二の性』(1949年)の中で、イナンナをはじめとする古代の強力な女性神々が、近代文化では男性の神々に取って代わられ、疎外されてきたと論じている<ref>Pryke, 2017, page196</ref>。ティクヴァ・フライマー・ケンスキーは、イナンナはシュメールの宗教において「社会的に受け入れがたい」原型である「家畜と結婚していない女性」を体現する「端的な人物」であったと論じている<ref>Pryke, 2017, page196</ref>。フェミニスト作家のヨハンナ・スタッキーは、イナンナがシュメールの宗教において中心的な存在であり、多様な権力を有していたことを指摘し、この考え方に反論している<ref>Pryke, 2017, page196</ref>。アッシリア研究者のジュリア・M. 古代における女性の地位の研究を専門とするアッシャー=グリーヴは、フリマー=ケンスキーのメソポタミア宗教研究全体を批判し、豊穣に焦点を当てた研究の問題点、依拠した資料の少なさ、パンテオンにおける女神の地位が社会の一般女性のそれを反映しているという見方(いわゆる「ミラー理論」)、さらに古代メソポタミアの宗教における女神の役割の変化の複雑さを正確に反映していないことを強調している<ref>Asher-Greve, Westenholz, 2013, p25-26</ref>。イローナ・ゾルネイは、フリマー・ケンスキーの方法論は誤りであるとする<ref>Zsolnay, 2009, p105</ref>。 | |

| − | + | ==== ネオペイガニズムとシュメール復元論において ==== | |

| + | イナンナの名前は、現代のネオペイガニズムやウィッカでも女神を指す言葉として使われている<ref>Rountree, 2017, page167</ref>。彼女の名前は、最も広く使われているウィッカの典礼の一つである「Burning Times Chant」<ref>Weston, Bennett, 2013, page165</ref>の中に出てくる<ref>Weston, Bennett, 2013, page165</ref>。イナンナの冥界への降臨は、ガードナー派ウィッカの最も人気のあるテキストの一つである「女神降臨」<ref>Buckland, 2001, pages74–75</ref>のインスピレーションとなった<ref>Buckland, 2001, pages74–75</ref>。 | ||

| − | == | + | == 日時(目安) == |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

{| class="toccolours collapsible nowraplinks" style="background-color:#fff; width:100%;" | {| class="toccolours collapsible nowraplinks" style="background-color:#fff; width:100%;" | ||

| − | | colspan="3" style="text-align:center; width:100%; background-color:# | + | | colspan="3" style="text-align:center; width:100%; background-color:#faa" |<span style="font-size:110%;">'''歴史的資料'''</span> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="background:# | + | | style="background:#fcc; text-align:right; border-bottom: 1px solid #aaa" | '''年月日''' |

| − | | style="background:# | + | | style="background:#fcc; text-align:left; border-bottom: 1px solid #aaa" | '''時代''' |

| − | | style="background:# | + | | style="background:#fcc; text-align:left; border-bottom: 1px solid #aaa" | '''出典''' |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="white-space:nowrap; background:# | + | | style="white-space:nowrap; background:#fdd; text-align:right;" | 5300–4100 BCE |

| − | | style="background:# | + | | style="background:#fee; text-align:left;" | ウバイド期 |

| style="text-align:left;" | | | style="text-align:left;" | | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="white-space:nowrap; background:# | + | | style="white-space:nowrap; background:#fdd; text-align:right;" | 4100–2900 BCE |

| − | | style="background:# | + | | style="background:#fee; text-align:left;" | ウルク期 |

| − | | style="text-align:left;" | | + | | style="text-align:left;" | ウルクの大杯<ref>Suter, 2014, page551</ref> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="white-space:nowrap; background:# | + | | style="white-space:nowrap; background:#fdd; text-align:right;" | 2900–2334 BCE |

| − | | style="background:# | + | | style="background:#fee; text-align:left;" | 初期王朝時代 |

| style="text-align:left;" | | | style="text-align:left;" | | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="white-space:nowrap; background:# | + | | style="white-space:nowrap; background:#fdd; text-align:right;" | 2334–2218 BCE |

| − | | style="background:# | + | | style="background:#fee; text-align:left;" | アッカド帝国 |

| − | | style="text-align:left;" | | + | | style="text-align:left;" | エンヘドゥアンナによる記述:<ref>Leick, 1998, pag=87</ref><ref>Collins, 1994, page111</ref><br /> |

| − | ''Nin-me-šara'', " | + | ''Nin-me-šara'', "イナンナの栄華"<br /> |

| − | ''In-nin ša-gur-ra'', " | + | ''In-nin ša-gur-ra'', "イナンナへの讃歌(イナンナC)"<br /> |

| − | ''In-nin me-huš-a'', " | + | ''In-nin me-huš-a'', "イナンナとエビフ山"<br /> |

| − | '' | + | ''神殿讃歌''<br /> |

| − | '' | + | ''ナンナへの賛歌'', "イナンナの栄華"<br /> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="white-space:nowrap; background:# | + | | style="white-space:nowrap; background:#fdd; text-align:right;" | 2218–2047 BCE |

| − | | style="background:# | + | | style="background:#fee; text-align:left;" | グティ王朝 |

| style="text-align:left;" | | | style="text-align:left;" | | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | style="white-space:nowrap; background:# | + | | style="white-space:nowrap; background:#fdd; text-align:right;" | 2047–1940 BCE |

| − | | style="background:# | + | | style="background:#fee; text-align:left;" | ウル第三王朝 |

| − | | style="text-align:left;" | '' | + | | style="text-align:left;" | ''エンメルカルとアラッタの王''<br /> |

| − | '' | + | ''ギルガメシュ叙事詩''<br /> |

| − | '' | + | ''イナンナとエンキ''<ref>Leick, 1998, page90</ref><br /> |

| − | '' | + | ''イナンナの冥界下り''<br /> |

|} | |} | ||

| − | == | + | == 参考文献他 == |

| − | * [ | + | * Wikipedia:[https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E3%82%A4%E3%83%8A%E3%83%B3%E3%83%8A イナンナ](最終閲覧日:22-12-08) |

| − | * | + | ** 前田徹『メソポタミアの王・神・世界観-シュメール人の王権観-』山川出版社、2003年10月。ISBN 4-634-64900-4 |

| − | * | + | ** 矢島文夫『メソポタミアの神話』筑摩書房、1982年、7月。 |

| − | * | + | ** 岡田明子・小林登志子『シュメル神話の世界 -粘土板に刻まれた最古のロマン』〈中公新書 1977〉2008年12月。ISBN 978-4-12-101977-6 |

| − | * | + | * Wikipedia:Inanna(最終閲覧日:23-01-02) |

| + | ** Abdi Kamyar, Elamo-Hittitica I: An Elamite Goddess in Hittite Court, Dabir (Digital Archive of Brief Notes & Iran Review), https://www.academia.edu/31797493, issue3, 2017, Jordan Center for Persian Studies , Irvine, 2021-08-10 | ||

| + | ** Ackerman Susan, 2006, 1989, Gender and Difference in Ancient Israel, Day, Peggy Lynne, https://books.google.com/books?id=38aX_-PqViIC&pg=PA116, Minneapolis, Minnesota, Fortress Press, isbn:978-0-8006-2393-7 | ||

| + | ** Al-Jallad Ahmad, On the origins of the god Ruḍaw and some remarks on the pre-Islamic North Arabian pantheon, Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, Cambridge University Press (CUP), 2021, volume31, issue3, pages559–571, issn:1356-1863, doi:10.1017/s1356186321000043, s2cid:233679011 | ||

| + | ** Bendt Alster, Tammuz(/Dumuzi), Reallexikon der Assyriologie, http://publikationen.badw.de/en/rla/index#11412, 2013, 2021-08-10 | ||

| + | ** Archi Alfonso, Diversity and Standardization, The Anatolian Fate-Goddesses and their Different Traditions, https://www.academia.edu/7003669, 2014, pages1–26, DE GRUYTER, München , doi:10.1524/9783050057576.1, isbn:978-3-05-005756-9 | ||

| + | ** Julia M. Asher-Greve, Joan G. Westenholz, https://www.zora.uzh.ch/id/eprint/135436/1/Asher-Greve_Westenholz_2013_Goddesses_in_Context.pdf, Goddesses in Context: On Divine Powers, Roles, Relationships and Gender in Mesopotamian Textual and Visual Sources, 2013, isbn:978-3-7278-1738-0 | ||

| + | ** Assante Julia, 2003, From Whores to Hierodules: The Historiographic Invention of Mesopotamian Female Sex Professionals, Ancient Art and Its Historiography, Donahue A. A., Fullerton Mark D. , Cambridge, England, Cambridge University Press, pages13–47 | ||

| + | ** Attinger Pascal, Inana et Ebih, Zeitschrift für Assyriologie, volume3, 1988, pages164–195 | ||

| + | ** Ayali-Darshan Noga, The Role of Aštabi in the Song of Ullikummi and the Eastern Mediterranean "Failed God" Stories, https://www.academia.edu/44462602, Journal of Near Eastern Studies, University of Chicago Press, volume73, issue1, 2014, issn:0022-2968, doi:10.1086/674665, pages95–103, s2cid:163770018 | ||

| + | ** Baring Anne, Cashford Jules, 1991, The Myth of the Goddess: Evolution of an Image, https://books.google.com/books?id=0XedISRtcZYC&pg=PT338, London, England, Penguin Books, isbn:978-0-14-019292-6 | ||

| + | ** Beckman Gary, Ištar of Nineveh Reconsidered, Journal of Cuneiform Studies, American Schools of Oriental Research, volume50, 1998, issn:=0022-0256, jstor:1360026, pages1–10, doi:10.2307/1360026 , s2cid:163362140, http://www.jstor.org/stable/1360026, 2021-07-28 | ||

| + | ** Beckman Gary, The Goddess Pirinkir and Her Ritual from Ḫattuša (CTH 644), Ktèma: Civilisations de l'Orient, de la Grèce et de Rome antiques, PERSEE Program, volume24, issue1, 1999, pages25–39, issn0221-5896 , doi:10.3406/ktema.1999.2206, hdl:2027.42/77419 | ||

| + | ** Beckman Gary, A Wise and Discerning Mind: Essays in Honor of Burke O. Long, Goddess Worship—Ancient and Modern, Brown Judaic Studies, 2000, pages11–24, doi:10.2307/j.ctvzgb93t.9, isbn:978-1-946527-90-5 , jstor:j.ctvzgb93t.9, hdl:2027.42/77415, s2cid:190264355, http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvzgb93t.9, 2021-08-10 | ||

| + | ** Beckman Gary, Recent Developments in Hittite Archaeology and History, Babyloniaca Hethitica: The "babilili-Ritual" from Bogazköy (CTH 718), https://www.researchgate.net/publication/44963754, Penn State University Press, 2002, doi:10.5325/j.ctv1bxh36t.6 | ||

| + | ** Beckman Gary, Hethitische Literatur: Überlieferungsprozesse, Textstrukturen, Ausdrucksformen und Nachwirken : Akten des Symposiums vom 18. bis 20. Februar 2010 in Bonn, Primordial Obstetrics. "The Song of Emergence" (CTH 344), https://www.academia.edu/48247742, Ugarit-Verlag, Münster, 2011, isbn:978-3-86835-063-0, oclc:768810899 | ||

| + | ** Behrens H., J. Klein, Ninegalla, Reallexikon der Assyriologie, http://publikationen.badw.de/en/rla/index#8599, 1998, 2021-08-10 | ||

| + | ** Bertman Stephen, 2003, Handbook to Life in Ancient Mesopotamia, Oxford University Press, Oxford, England, isbn:978-0-19-518364-1, https://books.google.com/books?id=1C4NKp4zgIQC&q=Papsukkal+%2B+Ninshubur&pg=PA124 | ||