イナンナ

イナンナがライオンの背に足をかけ、その前にニンシュブルが立って敬意を表している様子を描いた古代アッカド語の円筒印章(紀元前2334年頃~2154年頃)[1]

イナンナ(シュメール語:𒀭𒈹、翻字] DINANNA、音声転写: Inanna)は、シュメール神話における金星、愛や美、戦い、豊穣の女神。別名イシュタル。ウルク文化期(紀元前4000年-紀元前3100年)からウルクの守護神として崇拝されていたことが知られている(エアンナに祀られていた)。シンボルは藁束と八芒星(もしくは十六芒星)。聖樹はアカシア、聖花はギンバイカ、聖獣はライオン。

イナンナ(ɪˈnɑːnə; 𒀭𒈹、Dinanna, also 𒀭𒊩𒌆𒀭𒈾 Dnin-an-na[2])[3]は古代メソポタミアの愛と戦争と豊穣の女神である。また、美、性、神の正義、政治的権力とも関連している。シュメールでは「イナンナ」の名で、後にアッカド人、バビロニア人、アッシリア人によって「イシュタル(Ishtar、ˈɪʃtɑːr; 𒀭𒀹𒁯、Dištar[4] occasionally represented by the logogram 𒌋𒁯)」の名で崇拝された。イナンナは「天の女王」と呼ばれ、ウルクの町にあるエアンナ神殿が彼女の主要な信仰の場であり、守護神であった。金星と結びついた彼女は、象徴としてライオンや八芒星などが有名である。彼女の夫はドゥムジ神(後のタンムーズ神)であり、彼女の侍女は女神ニンシュブル(後に男神イラブレットやパプスカルと混同される)であった。

イナンナは少なくともウルク文化(前4000年頃-前3100年頃)の時代にはシュメールで崇拝されていたが、アッカドのサルゴンによる征服以前はほとんど信仰されていなかった。サルゴン王の時代以降、イナンナはシュメールの神殿の中で最も広く崇拝される神となり[4][5]、メソポタミア各地に神殿を持つようになった[5][6]。イナンナ/イシュタルの信仰は、様々な性儀礼と結びついていたと思われるが、この地域のシュメール人を継承・吸収した東セム語系の人々(アッカド人、アッシリア人、バビロニア人)にも受け継がれた。イナンナは特にアッシリアの人々に愛され、アッシリアの国神アシュールよりも上位に位置する神殿の最高神とされた。イナンナはヘブライ語の聖書に登場し、ウガリット語のアシュタルトやフェニキア語のアスタルテに大きな影響を与え、さらにギリシャ神話の女神アフロディーテの誕生にも影響を与えたとされる。イナンナへの信仰はその後も栄え、紀元1世紀から6世紀にかけて、キリスト教の影響により徐々に衰退していった。

イナンナはシュメールの他のどの神よりも多くの神話に登場する[7][8][9]。また、ネルガルに匹敵するほど多くの称号や 別名を有していた[10]。神話の多くは、彼女が他の神の領域を引き継ぐというものである。彼女は、知恵の神エンキから文明のプラスとマイナスのすべてを表すメー(mes)を授かったと信じられていた。また、天空の神アンからエアンナ神殿を譲り受けたとされる。イナンナは双子の弟ウトゥ(後のシャマシュ)と共に神の正義を執行した。自分の権威に挑戦したエビ山(Mount Ebih)を破壊し、寝込みを襲った庭師シュカレトゥダ(Shukaletuda)に怒りを爆発させ、ドゥムジを殺害した神の報復として盗賊女ビルル(Bilulu)を追跡して殺害したのである。アッカド語版の『ギルガメシュ叙事詩』では、イシュタルがギルガメシュに配偶者になるよう求めている。ギルガメシュがそれを拒否すると、彼女は天の雄牛を解き放ち、エンキドゥを死なせてしまい、その後ギルガメシュは自分の死と向き合うことになる。

イナンナ/イシュタルの最も有名な神話は、姉のエレシュキガルが支配する古代メソポタミアの冥界への降臨とそこからの帰還を描いた物語である。エレシュキガルの玉座に着いた彼女は、冥界の7人の審判によって有罪とされ、死に追いやられる。3日後、ニンシュブルはすべての神々にイナンナを連れ戻すように懇願する。エンキだけは、イナンナを救うために、性のない2人の人間を送り込んだ[私注 1]。彼らはイナンナを冥界から追い出すが、冥界の守護者であるガラは彼女の夫ドゥムジをイナンナの代わりとして冥界に引きずり下ろす。やがてドゥムジは1年の半分を天に帰ることを許され、姉妹のゲシュティアンナは残りの半分を冥界にとどまり、季節が循環することになる。

目次

- 1 語源

- 2 起源と発展

- 3 信仰

- 4 イコノグラフィー

- 5 特徴

- 6 家族

- 7 他の神々との習合と影響

- 8 シュメール語文献

- 9 Descent into the underworld

- 10 Later myths

- 11 Later influence

- 12 In popular culture

- 13 Dates (approximate)

- 14 See also

- 15 Notes

- 16 References

- 17 Further reading

- 18 External links

- 19 呼称

- 20 神話のなかのイナンナ

- 21 王権を授与する神としてのイナンナ

- 22 私的解説

- 23 参考文献

- 24 関連項目

- 25 私的注釈

- 26 参照

語源

イナンナとイシュタルはもともと無関係な別の神であったが[11]、アッカドのサルゴンの時代に混同され、実質的に同じ女神が2つの名前で呼ばれるようになったと学者たちは考えている[12]。(アッカド語のAna Kurnugê, qaqqari la târi, Sha naqba īmuruがイシュタルの名を用いているほかは、すべてイナンナの名を用いたテキストである[13]。) イナンナの名前はシュメール語で「天国の女性」を意味するnin-an-akに由来すると考えられるが[14][15]、イナンナの楔形記号(𒈹)は女性(lady、シュメール語:nin、楔型文字: 𒊩𒌆 SAL.TUG2)と空(sky、シュメール語:an、楔型文字: 𒀭 AN)を合字したものではないのではある[16][17][18]。こうしたことから、初期のアッシリア学者の中には、イナンナはもともと原ユーフラテスの女神で、後にシュメールの神殿に受け入れられたのではないかと考える者もいた。この考えは、イナンナが若く、他のシュメールの神々とは異なり、当初は明確な責任範囲を持たなかったと思われることから支持された[19]。 シュメール語以前にイラク南部にプロト・ユーフラティア語の基層言語が存在したという見方は、現代のアッシリア学者にはあまり受け入れられていない[20]。

イシュタルという名前は、アッカド、アッシリア、バビロニアの前サルゴン時代と後サルゴン時代の人名に登場する[21]。 その名はセム語由来[22][23]で、後世のウガリットやアラビア南部の碑文に登場する西セム語の神アッター(Attar)の名前に語源的に関連していると考えられる[24][25][私注 2]。開けの明星は兵法を司る男性神、宵の明星は愛術を司る女性神として考えられていたのかもしれない[26][私注 3]。アッカド人、アッシリア人、バビロニア人の間では、やがて男性神の名が女性神の名に取って代わったが[27]、イナンナとの広範囲な習合により、名前は男性形であってもイシュタルは女性としてとどまった[28]。

起源と発展

イナンナは、他のどの神よりも明確で矛盾した側面を持つため、古代シュメールの多くの研究者に問題を提起してきた[31]。彼女の起源については、大きく分けて2つの説がある[32]。第一の説は、イナンナはシュメール神話に登場する、それまで全く関係のなかった複数の神々が、全く異なる領域を持つ神々と習合した結果生まれたとするものである[33][34]。第二の説は、イナンナはもともとセム系の神で、シュメールのパンテオンが完全に構築された後に参入し、まだ他の神に割り当てられていないすべての役割を担ったとするものである[35]。

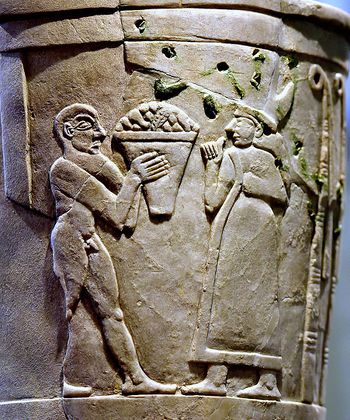

ウルク時代(前4000年頃〜前3100年頃)、イナンナはすでにウルクの都市と結び付いていた[36]。この時代、環状の頭部を持つ門柱のシンボルはイナンナと密接な関係があった[37]。有名な「ウルクの壷([Uruk Vase)」(ウルク3世時代の祭祀具の堆積物から発見)は、裸の男たちが椀や器、農作物の入った籠など様々な物を運び[38]、支配者と向き合う女性像に羊や山羊を連れていく姿が描かれている[39]。女性はイナンナの象徴である門柱の2本のねじれた葦の前に立ち[40]、男性は箱と杯の束を持っているが、これは後の楔形文字で神殿の高僧を意味するものである[41]。

ジェムデット・ナスル時代(紀元前3100年頃〜2900年頃)の印章には、ウル、ラルサ、ザバラム、ウルム、アリナ、そしておそらくケシュなど、様々な都市を表す記号が一定の順序で描かれている[42]。このリストには、ウルクでイナンナ信仰を支える都市からイナンナへの寄進が報告されていることが反映されていると思われる[43]。初期王朝時代(前2900年頃〜前2350年頃)のウルの第1期遺跡からは、イナンナのロゼットシンボルと組み合わせた、少し順序の異なる同様の印章が大量に発見されている[44]。この印章は、イナンナの崇拝のために用意された材料を保存するための倉庫を封印するために使用された[45]。

紀元前2600年頃のキシュのアガ王の腕輪、紀元前2400年頃のルガル=キサルシ王の石版など、イナンナの名を記した様々な碑文が知られている。

"全土の王アンと、その愛人イナンナのために、キシュの王ルガル=キサルシは中庭の壁を築いた。"

- ルガル=キサルシの碑文[46]。

アッカド帝国のサルゴンによる征服後のアッカド時代(前2334年頃〜前2154年頃)には、イナンナともともと独立していたイシュタルを広範囲に融合させ、事実上同一視されるようになった[47][48]。 アッカドの詩人エンヘドゥアンナはサルゴンの娘で、イシュタルと同一視したイナンナへの賛美歌を数多く書いている[49][50]。その結果[51]、イナンナ/イシュタル信仰は急増した[52][53][54]。エブラの発掘調査に早くから携わっていたアルフォンソ・アルキは、イシュタルはもともとユーフラテス川流域で崇拝されていた女神だと推測し、エブラとマリの両方の最も古い文献に、女神と砂漠のポプラとの関連が証明されていることを指摘した。アルキは、イナンナ、月の神(例えばシン)、性別の異なる太陽の神(シャマシュ/シャパシュ)を、メソポタミアと古代シリアの様々な初期セム族が共有する唯一の神であると考える。彼らはそれ以外、必ずしも重なり合わない異なる神殿を持っていたのである[55]。

信仰

グウェンドリン・レイクは、前サルゴニア時代にはイナンナの崇拝はむしろ限定的であったと仮定しているが[56]、他の専門家は、ウルク時代にはすでにウルクや他の多くの政治的拠点でイナンナは最も著名な神であったと主張している[57]。ニップル、ラガシュ、シュルパク、ザバラム、ウルに神殿があったが[58]、主な信仰の中心はウルクのエアンナ神殿で[59][60][61][62]、その名は「天国の家」(シュメール語:e2-anna、楔形文字:𒂍𒀭 E2.AN)を意味する[63] 。この紀元前4千年の都市の本来の守護神は「アン」であったとする研究もある[64]。イナンナに捧げられた後、この神殿には女神の巫女が住んでいたようである[65]。ザバラムはウルクに次いで初期のイナンナ信仰の重要な拠点であった。都市の名前は一般的にMUŠ3、UNUGと書かれ、それぞれ "イナンナ" と "聖域" を意味していた[66]。 ザバラムの都市女神はもともと別の神であった可能性があるが、その女神信仰はかなり早い時期にウルク人の女神に吸収された[67]。ヨアン・グッドニック・ウェステンホルツは、ザメの讃歌でイシュタランと結びついたNin-UM(読みと意味は不明)という名の女神が、ザバラムのイナンナの本来の姿であると提唱した[68]。

古アッカド時代には、イナンナはアガデの都市に関連するアッカドの女神イシュタルと習合した[69]。 この時代の讃美歌には、アッカド人のイシュタルが、ウルクのイナンナ、ザバラムのイナンナと並んで「ウルマシュのイナンナ」と呼ばれているものがある[70]。 イシュタル信仰とイナンナとの習合はサルゴンとその後継者によって奨励され[71]、その結果イシュタルはメソポタミアのパンテオンの中で最も広く崇拝される神々の一つとなるに至った[72]。サルゴン、ナラム-シン、シャル-カリ-シャリーの碑文では、イシュタルが最も頻繁に登場する神である[73]。

古バビロニア時代には、前述のウルク、ザバラム、アガデのほか、イリプが主な信仰の中心地であった[74]。また、彼女の信仰はウルクからキシュに伝わった[75]。

後世、ウルクでの信仰が盛んになる一方で[76]、上メソポタミア王国のアッシリア(現在のイラク北部、シリア北東部、トルコ南東部)、特にニネヴェ、アシュスール、アルベラ(現在のエルビル)でイシュタルの信仰が盛んになった[77]。アッシュールバニパル王の時代には、イシュタルはアッシリアの国神アシュールをも凌ぐ、アッシリアのパンテオンの中で最も重要で広く崇拝される神々に成長した[78]。アッシリアの第一神殿で発見された奉納品から、彼女が女性の間で人気のある神であったことがわかる[79]。

伝統的な性別の二元論に反対する者は、イナンナの信仰に深く関わっていた[80]。シュメール時代には、イナンナの神殿でガラ(gala)と呼ばれる神官たちが働き、哀歌や嘆きを奏でたという[81]。ガラになった男性は女性の名を名乗ることもあり、その歌はシュメール語のエメ・サル(eme-sal)という方言で詠まれた。この方言は、文学作品では通常、女性の登場人物が話すためのものである。シュメールの諺には、ガラが男性とアナルセックスをすることに定評があったことを示唆するものもあるようだ[82]。アッカド時代、イシュタルの神殿で女装して戦いの踊りを披露したイシュタルの召使がクーガルやアシンヌである[83]。アッカド語のことわざの中には、彼らが同性愛の性癖を持っていた可能性を示唆するものがいくつかあるようだ[84]。メソポタミアに関する著作で知られる人類学者グウェンドリン・レイクは、これらの人物を現代のインドのヒジュラになぞらえている[85]。アッカド語の讃美歌には、イシュタルが男性を女性に変えるという表現がある[86][87]。

紀元前20世紀後半、イナンナ信仰は、王がドゥムジに扮し、女神に扮したイナンナの大神官と儀式的に性交することで自らの正統性を確立する「聖なる結婚」の儀式があったと広く信じられていた[88][89][90][91]。しかし、この考えには疑問があり、文学作品に描かれた神聖な結婚が何らかの物理的な儀式を伴うものかどうか、その儀式が実際の性交を伴うものか、単に性交の象徴的な表現にすぎないのか、研究者の間で議論が続けられている[92][93]。古代近東の研究者であるルイーズ・M・プライクによれば、現在ではほとんどの学者が、神聖な結婚が実際に演じられる儀式であったとすれば、それは象徴的な性交に過ぎないと主張しているそうだ[94]。

イシュタル信仰は長い間、神聖な売春を伴うと考えられていたが[95]、現在では多くの学者の間で否定されている[96]。『イシュタリトゥム(ishtaritum)』として知られるヒエログループはイシュタルの神殿で働いていたとされるが[97]、そうした巫女が実際に性行為を行ったかどうかは不明であり[98]、現代の学者も何人かそうでないと論じている[99][100]。古代近東の女性たちは、イシュタルを崇拝し、灰で焼いたケーキ(カマーン・トゥムリ、kamān tumri)を捧げた[101]。この種の奉納は、アッカド語の讃美歌に記されている[102]。マリで発見されたいくつかの粘土のケーキ型は、大きなお尻で胸を押さえた裸の女性の形をしている[103]。この型から作られたケーキは、イシュタル自身を表現するためのものであったとする学者もいる。

イコノグラフィー

シンボル

イナンナ/イシュタルの最も一般的なシンボルは八芒星であった[106]が、正確な点の数は時々異なる[107]。また、六芒星も頻繁に登場するが、その象徴的な意味は不明である[108][私注 4]。八芒星はもともと天と一般的な関連性を持っていたようだが[109]、古バビロニア時代(前1830頃 - 前1531頃)には、特に金星と関連付けられるようになり、イシュタルはそれと同一視されるようになった[110]。この時期から、イシュタルの星は通常、円盤の中に収められるようになった[111]。後のバビロニア時代には、イシュタルの神殿で働く奴隷に八芒星の印章が押されることもあったという[112][113]。境界石や円筒印章には、シン(シュメール語でナンナ)の象徴である三日月やシャマシュ(シュメール語でウトゥ)の象徴である虹色の太陽円盤と一緒に八芒星が描かれることもある[114]。

イナンナの楔形文字の表意文字は、葦の鉤状のねじれた結び目で、豊饒と豊穣の象徴である倉の門柱を表している[115]。このロゼットはイナンナのもう一つの重要なシンボルであり、イナンナとイシュタルの習合後にもイシュタルのシンボルとして使われ続けている[116]。新アッシリア時代(紀元前911〜609年)には、ロゼットは八芒星に取って代わり、イシュタルの主要なシンボルとなった可能性がある[117]。アッシュール市のイシュタル神殿は、多数のロゼットで飾られていた[118]。

イナンナ/イシュタルはライオンと関連しており[119][120]、シュメール時代、古代メソポタミア人はライオンを権力の象徴とみなしていた[121]。ニップルのイナンナ神殿から出土した緑泥石製の鉢には、大蛇と戦う大きなネコが描かれており[122]、鉢に刻まれた楔形文字には「イナンナと蛇」とあり、ネコが女神を表していると考えられていることが示されている[123][私注 5]。アッカド時代には、イシュタルはライオンを属性とする重武装の女神として描かれることが多かった[124]。

鳩はイナンナ/イシュタルに関連する著名な動物でもある[125][126]。鳩は、紀元前3千年紀の初めにはイナンナに関連する祭具に描かれていた[127]。紀元前13世紀のアシュシュルのイシュタル神殿から鉛製の鳩の置物が発見され[128]、シリアのマリの壁画には、イシュタル神殿のヤシの木から巨大な鳩が姿を現しており[129]、女神自身が鳩の姿をとることもあったと考えられている[130]。

金星の女神として

イナンナは金星と関連しており、金星の名前はローマ時代のヴィーナスに由来している[131][132][133]。いくつかの讃美歌は、イナンナを惑星ヴィーナスの女神または擬人化として讃えている[134]。神学教授のジェフリー・クーリーは、多くの神話において、イナンナの動きは天空の金星の動きと対応しているのではないかと論じている[135]。イナンナの冥界への降臨は、他の神々とは異なり、冥界に降臨して天に戻ることができる。金星も同じように、西に沈み、東に昇るように見える[136]。冒頭の賛美歌では、イナンナが天界を離れ、山々と推定されるクルに向かう様子が描かれており、イナンナが西に昇り、沈む様子が再現されている[137]。『イナンナとシュカレトゥダ』では、シュカレトゥダがイナンナを探して天を駆け巡る様子が描かれている。これは、おそらく東と西の地平を探っているのだろう[138]。同じ神話の中で、イナンナは自分を襲った相手を探しながら、天空の金星の動きと呼応するような動きを何度もしている[139]。

金星の動きは不連続に見えるため(太陽に近いため何日も消えては別の地平線に再び現れる)、金星をひとつの存在として認識せず[140]、それぞれの地平線にある朝星と夕星の2つの別の星だとする文化もあった[141]。しかし、ジェムデット・ナスル時代の円筒印章は、古代シュメール人が朝星と夕星が同じ天体であることを知っていたことを示している[142]。 金星の不連続な動きは、神話やイナンナの二面性に関連する[143]。

現代の占星術では、イナンナが冥界に落ちる話は、金星の逆行と関連した天文現象に言及したものであると認識されている。逆行中の金星が太陽と下交差する7日前に、夕方の空から姿を消す。この消失から連接までの7日間が、降臨神話のベースとなった天文現象であると見られている。連接後、さらに7日間を経て、金星が朝の星として現れ、これが冥界からの上昇に対応する[144][145]。

アヌニートゥとしてのイナンナは、黄道十二宮の最後の星座である魚座の東の魚と関連していた[146][147]。彼女の配偶者であるドゥムジは、連続する第一の星座である牡羊座と関連していた[148]。

特徴

シュメール人は、イナンナを戦いと愛の女神として崇拝していた[149]。イナンナの物語は、他の神々が固定的な役割と限られた領域を持つのとは異なり、征服から征服へと移り変わっていく姿を描いている[150][151]。彼女は若く、気性が荒く、自分に与えられた以上の権力を常に求めているように描かれていた[152][153]。

イナンナは愛の女神として崇拝されていたが、結婚の女神でもなければ、母なる女神とみなされることもなかった[154][155]。 アンドリュー・R・ジョージは、「あらゆる神話によれば、イシュタルは(中略)気質的にそのような職務には向いていなかった」とまで言っている[156]。ジュリア・M・アッシャー・グレイヴは、イナンナが母神でないために特に重要であったとさえ(Asher-Greveが)提唱している[157]。イナンナは愛の女神として、メソポタミア人が呪文を唱える際によく定量的(要出典、August 2022)に呼び出された[158]。

イナンナの冥界への降臨では、イナンナは恋人ドゥムジに対して非常に気まぐれな態度で接している[159]。イナンナのこのような性格は、後のアッカド語標準訳『ギルガメシュ叙事詩』の中で、ギルガメシュがイシュタルの恋人たちへのひどい仕打ちを指摘する際に強調されている[160][161]。しかし、アッシリア学者のディーナ・カッツによれば、降臨神話におけるイナンナとドゥムジの関係の描写は異例であるとのことである[162][163]。

イナンナはシュメールの軍神の一人としても崇拝されていた[164][165]。彼女に捧げられた讃美歌のひとつに、こう書かれている。「彼女は、自分に従わない者たちに対して混乱と混沌を引き起こし、殺戮を加速し、恐ろしい輝きをまとって破壊的な洪水を誘発する。 争いや戦いのスピードが速く、疲れ知らずで、サンダルを履くのが彼女のゲームだ[166]。」戦いそのものが「イナンナの踊り」と呼ばれることもあった[167]。特にライオンにまつわるエピソードは、そんな彼女の性格を際立たせるものだった[168]。軍神としてイルニナ(「勝利」)の名で呼ばれることもあったが[169]、この諡号は他の神々にも適用され、さらにイシュタルではなくニンギシダ[170]につながる別個の女神として機能することもあった[171][172][173]。イシュタルの性質のこの側面を強調するもう一つの諡号は、アヌニトゥ(「武勇なるもの」)であった[174]。イルニナ同様、アヌニトゥも独立した神である可能性があり、ウル3世の文書で初めて証明された[175]。

アッシリアの王家の呪法は、イシュタルの主要な機能の両方を同時に呼び出すもので、効力と武勇を同様に取り除くためにイシュタルを呼び出した[176]。メソポタミアの文献によると、王が軍隊を率い、敵に勝利するような英雄的な特徴と性的能力は、相互に関連していると考えられていたようである[177]。

イナンナ/イシュタルは女神でありながら、その性別が曖昧になることがあった[178]。 ゲイリー・ベックマンは、「曖昧な性別識別」はイシュタル自身だけでなく、彼が「イシュタル型」と呼ぶ女神たち(シャウシュカ、ピニキール、ニンシアンナなど)の特徴であったと述べている[179]。後期の讃美歌には「彼女(イシュタル)はエンリルであり、ニニルである」というフレーズがあるが、これはイシュタルが高貴であると同時に、時として「二形」であることに言及しているのかもしれない[180]。ナナヤの讃歌には、バビロンのイシュタルの男性的な側面が、より標準的なさまざまな記述とともに言及されている[181]。しかし、イロナ・ズソンラニーは、イシュタルを「男性的な役割を果たす女性的な人物」としか表現していない[182]。

家族

イナンナの双子の兄は、太陽と正義の神ウトゥ(アッカド語ではシャマシュと呼ばれる)である[183][184][185]。シュメールの文献では、イナンナとウトゥは非常に親密な関係であることが示されており[186]、近親相姦に近い関係であるとする現代作家もいる[187][188]。 イナンナは冥界降臨の神話において、冥界の女王エレシュキガルを「姉」と呼んでいるが[189][190]、シュメール文学において2人の女神が一緒に現れることはほとんどなく[191]、神名帳でも同じカテゴリーに位置づけられていない[192]。フルリ語の影響により、いくつかの新アッシリアの資料(例えば罰則条項)では、イシュタルはアダドとも関連付けられており、フルリ神話のシャウシュカとその兄テシュブの関係を反映している[193]。

イナンナはナンナとその妻ニンガルを両親とする伝承が最も一般的である[194][195]。その例は、初期王朝時代の神リスト[196]、エンリルとニンリルがイナンナに力を授けたことを伝えるイシュメ・ダガンの賛歌[197]、ナナヤへの後期シンクレティック賛歌[198]、ハトゥサからのアッカドの儀式など様々な資料に存在している[199]。ウルクではイナンナは通常、天空神アンの娘とみなされていたとする著者もいるが[200][201][202]、アンを父親とする言及は、アンはナンナの祖先としての地位にあるので、アンの娘としての地位に言及しているだけという可能性もある[203]。文学作品ではエンリルやエンキが彼女の父親と呼ばれることがあるが[204][205][206]、主要な神が「父親」であるという言及も、年功を示す諡号としてこの語が使われる例となり得る[207]。

羊飼いの神であるドゥムジッド(後のタンムズ)は通常イナンナの夫とされるが[208]、いくつかの解釈によればイナンナの彼に対する誠意は疑わしい[209]。冥界降臨の神話の中で、彼女はドゥムジッドを見捨て、ガラの悪魔が自分の代わりとして彼を冥界に引きずり下ろすことを許可する[210][211]。別の神話「ドゥムジの帰還」では、イナンナはドゥムジの死を悼み、最終的に1年の半分だけドゥムジを天界に戻して一緒に暮らせるようにすることを命じた[212][213]。ディーナ・カッツは、『イナンナの降臨』における二人の関係の描写は珍しいと指摘する[214]。それは、ドゥムジの死に関する他の神話における二人の関係の描写とは似ておらず、その責任はほとんどイナンナではなく、悪魔や人間の盗賊にさえある[215]。イナンナとドゥムジの出会いを描いた恋の詩は、研究者によって多くの類話が収集されている[216]。しかし、イナンナ/イシュタルは必ずしもドゥムジと関連しているわけではなく、イナンナ/イシュタルが地方に出現することもあった[217]。 キシュでは、都市の主神ザババ(軍神)がイシュタルのその地方での配偶者とされていたが[218]、古バビロニア時代以降、ラガシュから伝わったバウがその配偶者となり(メソポタミア神話によく見られる、軍神と薬神のカップル[219])、代わりにキシュのイシュタルを単独で崇め始めるようになったという[220]。

イナンナは通常、子孫を持つとは記述されていないが[221]、ルガルバンダの神話やウル第三王朝(前2112年頃 - 2004年頃)の一棟の碑文において、軍神シャラが彼女の息子として記述されている[222]。 また彼女は時にルーラル[223][私注 6](他のテキストではニンスンの息子として記述)の母親と見なされたこともある[224]。ウィルフレッド・G・ランバートは、『イナンナの降臨』の文脈で、イナンナとルーラルの関係を「近いが特定できない」と表現している[225]。また、恋愛の女神であるナナヤを娘とみなす証拠も同様に少ない(歌、奉納式、誓約)が、いずれも神々の親密さを示す諡号に過ぎず、実際の親子を示すものではない可能性もある[226]。

サッカル

イナンナの助祭(サッカル)は女神ニンシュブールであり[227]、イナンナと相互の献身的な関係であった[228]。いくつかのテキストでは、ニンシュブールはイナンナの仲間としてドゥムジのすぐ後に、彼女の親族の一部よりも前に記載されており[229]、あるテキストでは「愛する宰相、ニンシュブール」というフレーズも登場する[230]。別のテキストでは、イナンナの側近の神々のリストにおいて、もともとイナンナ自身の仮身であった可能性のあるナナヤ[231]よりもニンシュブールの方が先にリストアップされている[232]。ヒッタイトの古文書から知られるアッカドの儀式文では、イシュタルのサッカルが彼女の家族(シン、ニンガル、シャマシュ)と共に呼び出されている[233]。

イナンナの側近として神リストに頻繁に登場するのは、ナナヤ女神(通常ドゥムジとニンシュブールのすぐ後ろに位置する)、カニスラ、ガズババ、ビジラだが、これらはいずれもこの文脈とは別に、さまざまな構成で互いに関連づけられるものだった[234][235]。

他の神々との習合と影響

サルゴンとその後継者の時代にはイナンナとイシュタルが完全に融合していたことに加え[236]、程度の差こそあれ、多くの神々[237]と習合していた。最も古い習合の賛美歌はイナンナに捧げられたものであり[238]、初期王朝時代のものとされている[239]。古代の書記によって編纂された多くの神名帳には、同様の女神を列挙した「イナンナ・グループ」の項目があり[240]、『アン=アヌム』(全7枚)のタブレットIVは、その内容のほとんどがイシュタルの同等者の名前、称号、様々な従者であることから「イシュタルのタブレット」として知られている[241]。現代の研究者の中には、イシュタル型という言葉を用いて、この種の特定の人物を定義している人もいる[242][243]。ある地域の「すべてのイシュタル」に言及する文章もあった[244]。

後世、バビロニアではイシュタルの名が総称(「女神」)として使われることもあり、またイナンナの対語表記がBēltuとされ、さらに混同されることもあった[245]。アッカド語で書かれたエラム語の碑文に「マンザット・イシュタル」という言葉があり、これは「マンザット女神」という意味であろう[246]。

具体的事例

- アスタルト: マリやエブラのような都市では、東セム語と西セム語の名前(イシュタルとアシュタルト)は基本的に互換性があるとみなされていた[247]。しかし、西洋の女神はメソポタミアのイシュタルのような幽体離脱の性格を持っていないことが明らかである[248]。ウガリット語の神々のリストと儀式のテキストは、地元のアスタルトをイシュタルとフルリのイシャラの両方と同一視している[249]。

- イシャラ:イシュタルとの関連から[250]、シリアの女神イシャラはメソポタミアにおけるイシュタル(およびナナヤ)と同様に「愛の女性」としてみなされるようになった[251][252]。しかし、フルリ・ヒッタイトの文献では、イシャラは代わりに冥界の女神アラーニと結び付けられ、さらに誓いの女神として機能した[253][254]。

- ナナヤ:というのも、アッシリア学者のフランス・ウィッガーマンによれば、ナナヤの名前はもともとイナンナの呼称であった(おそらく「私のイナンナ!」という呼びかけの役割を果たした)ため、イナンナと非常に密接な関係にある女神であった[255]。ナナヤはエロティックな恋愛に関連していたが、やがて戦争的な側面も持つようになる(「ナナヤ・ユルサバ」)[256]。ラルサではイナンナの機能は事実上3つの人格の間で分割され、イナンナ自身、愛の女神としてのナナヤ、星女神としてのニンシアンナからなる三位一体として崇拝された[257]。イナンナ/イシュタルとナナヤは、しばしば詩の中で偶然あるいは意図的に混同された[258]。

- ニネンガル:当初は独立した存在であったが、古バビロニア時代から「ニネンガル」がイナンナの称号として使われ、神名帳では通常ニンシアンナと並んで「イナンナ・グループ」の一員となった[259]。「ニネンガル」の諡号としての用例は、ETCSLの「Hymn to Inana as Ninegala (Inana D)」と指定されているテキストに見られる。

- ニニシナ:また、特殊な例として、薬の女神ニニシナとイナンナが政治的な理由で習合を起こしたことがある[260]。イシンは一時ウルクの支配権を失い、王権の源泉である女神をイナンナと同一視し(イナンナに似た戦いの性格を持たせ)、この問題を神学的に解決しようとしたのであろう[261]。その結果、多くの文献でニニシナは、同じような名前のニンシアンナと類似していると見なされ、イナンナの化身として扱われるようになった[262]。 その結果、ニニシナとイシン王との「神聖な結婚」の儀式が行われた可能性もある[263] 。

- ニンシアンナ:は、性別が異なる金星の神である[264]。ニンシアンナは、ラルサのリム・シン(彼は特に「私の王」という言葉を使った)やシッパル、ウル、ギルスの文書では男性として言及されているが、神名リストや天文文書では「星のイシュタル」と呼ばれており、イシュタルの金星の擬人化としての役割に関する呼称もこの神に当てられている[265]。また、ニンシアンナは女性の神として知られていたところもあり、その場合は「天の赤い女王」と理解することができる[266]。

- ピニキル:元々はエラムの女神で、メソポタミアで認識され、その結果、フルリ人やヒッタイト人の間で、機能が似ていることからイシュタルに相当する女神として認識されるようになった。神々のリストでは、彼女は星神(ニンシアンナ)として特定されている[267]。ヒッタイトの儀式では、彼女はdIŠTARという記号で識別され、シャマシュ、スエン、ニンガルが彼女の家族として言及され、エンキとイシュタルのサッカルも呼び出された[268]。ピニキルはエラムでは愛と性の女神[269]、天上の神(「天の愛人」)であった[270]。イシュタルやニシアンナとの習合により、ピニキルはフルリ・ヒッタイトの資料では女性神、男性神として言及されている[271]。

- シャウシュカ:彼女の名前はフルリ・ヒッタイトの文献ではdIŠTARという記号でしばしば記述された。メソポタミアでは「スバルトゥのイシュタル」という名で知られている[272]。彼女特有の要素は、後世、アッシリアのイシュタル神格(ニネベのイシュタル)と結びつけられることになる[273]。彼女の侍女ニナッタとクリッタは、アッシュールの神殿でイシュタルに仕える神々の輪の中に組み込まれた[274][275]。

時代遅れの説

過去に一部の研究者は、イシュタルをアムルゥに関連する西セム語のアティラート(アシェラ)のバビロニアにおける反映である小女神アシュラトゥと結び付けようとしたが[276]、スティーブ・A・ウィギンズが実証したように、この説は根拠のないものであった[277]。なぜなら、この2人が混同されていた、あるいは単に混同されていたという唯一の証拠は、イシュタルとアシュラトゥが同じ諡号を共有していたという事実であり[190]、しかし同じ諡号はマルドゥク、ニントゥル、ネガル、スエンにも適用されており[278]、神名リストなどの資料にはさらなる証拠は見当たらなかったからだ[279]。また、ウガリット語のイシュタルの同義語であるアスタルト(Ashtart)が、アモリ人によりアティラートと混同、混同された形跡はない[280]。

シュメール語文献

起源的な神話

「エンキと世界秩序の詩」(ETCSL 1.1.3)は、まずエンキ神とその宇宙組織の設立を描いている[281]。

The poem of Enki and the World Order (ETCSL 1.1.3) begins by describing the god Enki and his establishment of the cosmic organization of the universe. Towards the end of the poem, Inanna comes to Enki and complains that he has assigned a domain and special powers to all of the other gods except for her.テンプレート:Sfn She declares that she has been treated unfairly.テンプレート:Sfn Enki responds by telling her that she already has a domain and that he does not need to assign her one.テンプレート:Sfn

The myth of "Inanna and the Huluppu Tree", found in the preamble to the epic of Gilgamesh, Enkidu, and the Netherworld (ETCSL 1.8.1.4),テンプレート:Sfn centers around a young Inanna, not yet stable in her power.テンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfn It begins with a huluppu tree, which Kramer identifies as possibly a willow,テンプレート:Sfn growing on the banks of the river Euphrates.テンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfn Inanna moves the tree to her garden in Uruk with the intention to carve it into a throne once it is fully grown.テンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfn The tree grows and matures, but the serpent "who knows no charm", the Anzû-bird, and Lilitu (Ki-Sikil-Lil-La-Ke in Sumerian),[282] seen by some as the Sumerian forerunner to the Lilith of Jewish folklore, all take up residence within the tree, causing Inanna to cry with sorrow.テンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfn The hero Gilgamesh, who, in this story, is portrayed as her brother, comes along and slays the serpent, causing the Anzû-bird and Lilitu to flee.テンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfn Gilgamesh's companions chop down the tree and carve its wood into a bed and a throne, which they give to Inanna,テンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfn who fashions a pikku and a mikku (probably a drum and drumsticks respectively, although the exact identifications are uncertain),テンプレート:Sfn which she gives to Gilgamesh as a reward for his heroism.テンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfn

The Sumerian hymn Inanna and Utu contains an etiological myth describing how Inanna became the goddess of sex.テンプレート:Sfn At the beginning of the hymn, Inanna knows nothing of sex,テンプレート:Sfn so she begs her brother Utu to take her to Kur (the Sumerian underworld),テンプレート:Sfn so that she may taste the fruit of a tree that grows there,テンプレート:Sfn which will reveal to her all the secrets of sex.テンプレート:Sfn Utu complies and, in Kur, Inanna tastes the fruit and becomes knowledgeable.テンプレート:Sfn The hymn employs the same motif found in the myth of Enki and Ninhursag and in the later Biblical story of Adam and Eve.テンプレート:Sfn

The poem Inanna Prefers the Farmer (ETCSL 4.0.8.3.3) begins with a rather playful conversation between Inanna and Utu, who incrementally reveals to her that it is time for her to marry.テンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfn She is courted by a farmer named Enkimdu and a shepherd named Dumuzid.テンプレート:Sfn At first, Inanna prefers the farmer,テンプレート:Sfn but Utu and Dumuzid gradually persuade her that Dumuzid is the better choice for a husband, arguing that, for every gift the farmer can give to her, the shepherd can give her something even better.テンプレート:Sfn In the end, Inanna marries Dumuzid.テンプレート:Sfn The shepherd and the farmer reconcile their differences, offering each other gifts.テンプレート:Sfn Samuel Noah Kramer compares the myth to the later Biblical story of Cain and Abel because both myths center around a farmer and a shepherd competing for divine favor and, in both stories, the deity in question ultimately chooses the shepherd.テンプレート:Sfn

Conquests and patronage

Inanna and Enki (ETCSL t.1.3.1) is a lengthy poem written in Sumerian, which may date to the Third Dynasty of Ur (c. 2112 BCE – c. 2004 BCE);テンプレート:Sfn it tells the story of how Inanna stole the sacred mes from Enki, the god of water and human culture.テンプレート:Sfn In ancient Sumerian mythology, the mes were sacred powers or properties belonging to the gods that allowed human civilization to exist.テンプレート:Sfn Each me embodied one specific aspect of human culture.テンプレート:Sfn These aspects were very diverse and the mes listed in the poem include abstract concepts such as Truth, Victory, and Counsel, technologies such as writing and weaving, and also social constructs such as law, priestly offices, kingship, and prostitution. The mes were believed to grant power over all the aspects of civilization, both positive and negative.テンプレート:Sfn

In the myth, Inanna travels from her own city of Uruk to Enki's city of Eridu, where she visits his temple, the E-Abzu.テンプレート:Sfn Inanna is greeted by Enki's sukkal, Isimud, who offers her food and drink.テンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfn Inanna starts up a drinking competition with Enki.テンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfn Then, once Enki is thoroughly intoxicated, Inanna persuades him to give her the mes.テンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfn Inanna flees from Eridu in the Boat of Heaven, taking the mes back with her to Uruk.テンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfn Enki wakes up to discover that the mes are gone and asks Isimud what has happened to them.テンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfn Isimud replies that Enki has given all of them to Inanna.テンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfn Enki becomes infuriated and sends multiple sets of fierce monsters after Inanna to take back the mes before she reaches the city of Uruk.テンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfn Inanna's sukkal Ninshubur fends off all of the monsters that Enki sends after them.テンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfn Through Ninshubur's aid, Inanna successfully manages to take the mes back with her to the city of Uruk.テンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfn After Inanna escapes, Enki reconciles with her and bids her a positive farewell.テンプレート:Sfn It is possible that this legend may represent a historic transfer of power from the city of Eridu to the city of Uruk.テンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfn It is also possible that this legend may be a symbolic representation of Inanna's maturity and her readiness to become the Queen of Heaven.テンプレート:Sfn

The poem Inanna Takes Command of Heaven is an extremely fragmentary, but important, account of Inanna's conquest of the Eanna temple in Uruk.テンプレート:Sfn It begins with a conversation between Inanna and her brother Utu in which Inanna laments that the Eanna temple is not within their domain and resolves to claim it as her own.テンプレート:Sfn The text becomes increasingly fragmentary at this point in the narrative,テンプレート:Sfn but appears to describe her difficult passage through a marshland to reach the temple while a fisherman instructs her on which route is best to take.テンプレート:Sfn Ultimately, Inanna reaches her father An, who is shocked by her arrogance, but nevertheless concedes that she has succeeded and that the temple is now her domain.テンプレート:Sfn The text ends with a hymn expounding Inanna's greatness.テンプレート:Sfn This myth may represent an eclipse in the authority of the priests of An in Uruk and a transfer of power to the priests of Inanna.テンプレート:Sfn

Inanna briefly appears at the beginning and end of the epic poem Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta (ETCSL 1.8.2.3). The epic deals with a rivalry between the cities of Uruk and Aratta. Enmerkar, the king of Uruk, wishes to adorn his city with jewels and precious metals, but cannot do so because such minerals are only found in Aratta and, since trade does not yet exist, the resources are not available to him.テンプレート:Sfn Inanna, who is the patron goddess of both cities,テンプレート:Sfn appears to Enmerkar at the beginning of the poemテンプレート:Sfn and tells him that she favors Uruk over Aratta.テンプレート:Sfn She instructs Enmerkar to send a messenger to the lord of Aratta to ask for the resources Uruk needs.テンプレート:Sfn The majority of the epic revolves around a great contest between the two kings over Inanna's favor.テンプレート:Sfn Inanna reappears at the end of the poem to resolve the conflict by telling Enmerkar to establish trade between his city and Aratta.テンプレート:Sfn

Justice myths

Inanna and her brother Utu were regarded as the dispensers of divine justice,テンプレート:Sfn a role which Inanna exemplifies in several of her myths.テンプレート:Sfn Inanna and Ebih (ETCSL 1.3.2), otherwise known as Goddess of the Fearsome Divine Powers, is a 184-line poem written by the Akkadian poet Enheduanna describing Inanna's confrontation with Mount Ebih, a mountain in the Zagros mountain range.テンプレート:Sfn The poem begins with an introductory hymn praising Inanna.テンプレート:Sfn The goddess journeys all over the entire world, until she comes across Mount Ebih and becomes infuriated by its glorious might and natural beauty,テンプレート:Sfn considering its very existence as an outright affront to her own authority.テンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfn She rails at Mount Ebih, shouting:

Inanna petitions to An, the Sumerian god of the heavens, to allow her to destroy Mount Ebih.テンプレート:Sfn An warns Inanna not to attack the mountain,テンプレート:Sfn but she ignores his warning and proceeds to attack and destroy Mount Ebih regardless.テンプレート:Sfn In the conclusion of the myth, she explains to Mount Ebih why she attacked it.テンプレート:Sfn In Sumerian poetry, the phrase "destroyer of Kur" is occasionally used as one of Inanna's epithets.テンプレート:Sfn

テンプレート:AnchorThe poem Inanna and Shukaletuda (ETCSL 1.3.3) begins with a hymn to Inanna, praising her as the planet Venus.テンプレート:Sfn It then introduces Shukaletuda, a gardener who is terrible at his job. All of his plants die, except for one poplar tree.テンプレート:Sfn Shukaletuda prays to the gods for guidance in his work. To his surprise, the goddess Inanna sees his one poplar tree and decides to rest under the shade of its branches.テンプレート:Sfn Shukaletuda removes her clothes and rapes Inanna while she sleeps.テンプレート:Sfn When the goddess wakes up and realizes she has been violated, she becomes furious and determines to bring her attacker to justice.テンプレート:Sfn In a fit of rage, Inanna unleashes horrible plagues upon the Earth, turning water into blood.テンプレート:Sfn Shukaletuda, terrified for his life, pleads his father for advice on how to escape Inanna's wrath.テンプレート:Sfn His father tells him to hide in the city, amongst the hordes of people, where he will hopefully blend in.テンプレート:Sfn Inanna searches the mountains of the East for her attacker,テンプレート:Sfn but is not able to find him.テンプレート:Sfn She then releases a series of storms and closes all roads to the city, but is still unable to find Shukaletuda,テンプレート:Sfn so she asks Enki to help her find him, threatening to leave her temple in Uruk if he does not.テンプレート:Sfn Enki consents and Inanna flies "across the sky like a rainbow".テンプレート:Sfn Inanna finally locates Shukaletuda, who vainly attempts to invent excuses for his crime against her. Inanna rejects these excuses and kills him.テンプレート:Sfn Theology professor Jeffrey Cooley has cited the story of Shukaletuda as a Sumerian astral myth, arguing that the movements of Inanna in the story correspond with the movements of the planet Venus.テンプレート:Sfn He has also stated that, while Shukaletuda was praying to the goddess, he may have been looking toward Venus on the horizon.テンプレート:Sfn

The text of the poem Inanna and Bilulu (ETCSL 1.4.4), discovered at Nippur, is badly mutilatedテンプレート:Sfn and scholars have interpreted it in a number of different ways.テンプレート:Sfn The beginning of the poem is mostly destroyed,テンプレート:Sfn but seems to be a lament.テンプレート:Sfn The intelligible part of the poem describes Inanna pining after her husband Dumuzid, who is in the steppe watching his flocks.テンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfn Inanna sets out to find him.テンプレート:Sfn After this, a large portion of the text is missing.テンプレート:Sfn When the story resumes, Inanna is being told that Dumuzid has been murdered.テンプレート:Sfn Inanna discovers that the old bandit woman Bilulu and her son Girgire are responsible.テンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfn She travels along the road to Edenlila and stops at an inn, where she finds the two murderers.テンプレート:Sfn Inanna stands on top of a stoolテンプレート:Sfn and transforms Bilulu into "the waterskin that men carry in the desert",テンプレート:Sfnm forcing her to pour the funerary libations for Dumuzid.テンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfn

Descent into the underworld

Two different versions of the story of Inanna/Ishtar's descent into the underworld have survived:テンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfn a Sumerian version dating to the Third Dynasty of Ur (circa 2112 BCE – 2004 BCE) (ETCSL 1.4.1)テンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfn and a clearly derivative Akkadian version from the early second millennium BCE.テンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Efn The Sumerian version of the story is nearly three times the length of the later Akkadian version and contains much greater detail.テンプレート:Sfn

Sumerian version

In Sumerian religion, the Kur was conceived of as a dark, dreary cavern located deep underground;テンプレート:Sfn life there was envisioned as "a shadowy version of life on earth".テンプレート:Sfn It was ruled by Inanna's sister, the goddess Ereshkigal.テンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfn Before leaving, Inanna instructs her minister and servant Ninshubur to plead with the deities Enlil, Nanna, An, and Enki to rescue her if she does not return after three days.テンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfn The laws of the underworld dictate that, with the exception of appointed messengers, those who enter it may never leave.テンプレート:Sfn Inanna dresses elaborately for the visit; she wears a turban, wig, lapis lazuli necklace, beads upon her breast, the 'pala dress' (the ladyship garment), mascara, a pectoral, and golden ring, and holds a lapis lazuli measuring rod.テンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfn Each garment is a representation of a powerful me she possesses.テンプレート:Sfn

Inanna pounds on the gates of the underworld, demanding to be let in.テンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfn The gatekeeper Neti asks her why she has comeテンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfn and Inanna replies that she wishes to attend the funeral rites of Gugalanna, the "husband of my elder sister Ereshkigal".テンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfn Neti reports this to Ereshkigal,テンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfn who tells him: "Bolt the seven gates of the underworld. Then, one by one, open each gate a crack. Let Inanna enter. As she enters, remove her royal garments."テンプレート:Sfn Perhaps Inanna's garments, unsuitable for a funeral, along with Inanna's haughty behavior, make Ereshkigal suspicious.テンプレート:Sfn Following Ereshkigal's instructions, Neti tells Inanna she may enter the first gate of the underworld, but she must hand over her lapis lazuli measuring rod. She asks why, and is told, "It is just the ways of the underworld." She obliges and passes through. Inanna passes through a total of seven gates, at each one removing a piece of clothing or jewelry she had been wearing at the start of her journey,テンプレート:Sfn thus stripping her of her power.テンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfn When she arrives in front of her sister, she is naked:テンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfn

Three days and three nights pass, and Ninshubur, following instructions, goes to the temples of Enlil, Nanna, An, and Enki, and pleads with each of them to rescue Inanna.テンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfn The first three deities refuse, saying Inanna's fate is her own fault,テンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfn but Enki is deeply troubled and agrees to help.テンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfn He creates two sexless figures named gala-tura and the kur-jara from the dirt under the fingernails of two of his fingers.テンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfn He instructs them to appease Ereshkigalテンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfn and, when she asks them what they want, ask for the corpse of Inanna, which they must sprinkle with the food and water of life.テンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfn When they come before Ereshkigal, she is in agony like a woman giving birth.テンプレート:Sfn She offers them whatever they want, including life-giving rivers of water and fields of grain, if they can relieve her,テンプレート:Sfn but they refuse all of her offers and ask only for Inanna's corpse.テンプレート:Sfn The gala-tura and the kur-jara sprinkle Inanna's corpse with the food and water of life and revive her.テンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfn Galla demons sent by Ereshkigal follow Inanna out of the underworld, insisting that someone else must be taken to the underworld as Inanna's replacement.テンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfn They first come upon Ninshubur and attempt to take her,テンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfn but Inanna stops them, insisting that Ninshubur is her loyal servant and that she had rightfully mourned for her while she was in the underworld.テンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfn They next come upon Shara, Inanna's beautician, who is still in mourning.テンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfn The demons attempt to take him, but Inanna insists that they may not, because he had also mourned for her.テンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfn The third person they come upon is Lulal, who is also in mourning.テンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfn The demons try to take him, but Inanna stops them once again.テンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfn

Finally, they come upon Dumuzid, Inanna's husband.テンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfn Despite Inanna's fate, and in contrast to the other individuals who were properly mourning her, Dumuzid is lavishly clothed and resting beneath a tree, or upon her throne, entertained by slave-girls. Inanna, displeased, decrees that the galla shall take him.テンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfn The galla then drag Dumuzid down to the underworld.テンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfn Another text known as Dumuzid's Dream (ETCSL 1.4.3) describes Dumuzid's repeated attempts to evade capture by the galla demons, an effort in which he is aided by the sun-god Utu.テンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Efn

In the Sumerian poem The Return of Dumuzid, which begins where The Dream of Dumuzid ends, Dumuzid's sister Geshtinanna laments continually for days and nights over Dumuzid's death, joined by Inanna, who has apparently experienced a change of heart, and Sirtur, Dumuzid's mother.テンプレート:Sfn The three goddesses mourn continually until a fly reveals to Inanna the location of her husband.テンプレート:Sfn Together, Inanna and Geshtinanna go to the place where the fly has told them they will find Dumuzid.テンプレート:Sfn They find him there and Inanna decrees that, from that point onwards, Dumuzid will spend half of the year with her sister Ereshkigal in the underworld and the other half of the year in Heaven with her, while his sister Geshtinanna takes his place in the underworld.テンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfn

Akkadian version

This version had two manuscripts found in the Library of Ashurbanipal and a third was found in Asshur, all dating from the first half of the first millennium before the common era.テンプレート:Sfn Of the Ninevite version, the first cuneiform version was published in 1873 by François Lenormant, and the transliterated version was published by Peter Jensen in 1901.テンプレート:Sfn Its title in Akkadian is Ana Kurnugê, qaqqari la târi.テンプレート:Sfn

The Akkadian version begins with Ishtar approaching the gates of the underworld and demanding the gatekeeper to let her in:

The gatekeeper (whose name is not given in the Akkadian versionテンプレート:Sfn) hurries to tell Ereshkigal of Ishtar's arrival. Ereshkigal orders him to let Ishtar enter, but tells him to "treat her according to the ancient rites".テンプレート:Sfn The gatekeeper lets Ishtar into the underworld, opening one gate at a time.テンプレート:Sfn At each gate, Ishtar is forced to shed one article of clothing. When she finally passes the seventh gate, she is naked.テンプレート:Sfn In a rage, Ishtar throws herself at Ereshkigal, but Ereshkigal orders her servant Namtar to imprison Ishtar and unleash sixty diseases against her.テンプレート:Sfn

After Ishtar descends to the underworld, all sexual activity ceases on earth.テンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfn The god Papsukkal, the Akkadian counterpart to Ninshubur,テンプレート:Sfn reports the situation to Ea, the god of wisdom and culture.テンプレート:Sfn Ea creates an androgynous being called Asu-shu-namir and sends them to Ereshkigal, telling them to invoke "the name of the great gods" against her and to ask for the bag containing the waters of life. Ereshkigal becomes enraged when she hears Asu-shu-namir's demand, but she is forced to give them the water of life. Asu-shu-namir sprinkles Ishtar with this water, reviving her. Then, Ishtar passes back through the seven gates, receiving one article of clothing back at each gate, and exiting the final gate fully clothed.テンプレート:Sfn

Interpretations in modern assyriology

Dina Katz, an authority on Sumerian afterlife beliefs and funerary customs, considers the narrative of Inanna's descent to be a combination of two distinct preexisting traditions rooted in broader context of Mesopotamian religion.

In one tradition, Inanna was only able to leave the underworld with the help of Enki's trick, with no mention of the possibility of finding a substitute.テンプレート:Sfn This part of the myth belongs to the genre of myths about deities struggling to obtain power, glory etc. (such as Lugal-e or Enuma Elish),テンプレート:Sfn and possibly served as a representation of Inanna's character as a personification of a periodically vanishing astral body.テンプレート:Sfn According to Katz, the fact that Inanna's instructions to Ninshubur contain a correct prediction of her eventual fate, including the exact means of her rescue, show that the purpose of this composition was simply highlighting Inanna's ability to traverse both the heavens and the underworld, much like how Venus was able to rise over and over again.テンプレート:Sfn She also points out Inanna's return has parallels in some Udug-hul incantations.テンプレート:Sfn

Another was simply one of the many myths about the death of Dumuzi (such as Dumuzi's Dream or Inana and Bilulu; in these myths Inanna is not to blame for his death),テンプレート:Sfn tied to his role as an embodiment of vegetation. She considers it possible that the connection between the two parts of the narrative was meant to mirror some well attested healing rituals which required a symbolic substitute of the person being treated.テンプレート:Sfn

Katz also notes that the Sumerian version of the myth is not concerned with matters of fertility, and points out any references to it (e.g. to nature being infertile while Ishtar is dead) were only added in later Akkadian translations;テンプレート:Sfn so was the description of Tammuz's funeral.テンプレート:Sfn The purpose of these changes was likely to make the myth closer to cultic traditions linked to Tammuz, namely the annual mourning of his death followed by celebration of a temporary return.テンプレート:Sfn According to Katz it is notable that known many copies of the later versions of the myth come from Assyrian cities which were known for their veneration of Tammuz, such as Ashur and Nineveh.テンプレート:Sfn

Other interpretations

A number of less scholarly interpretations of the myth arose through the 20th century, many of them rooted in the tradition of Jungian analysis rather than assyriology. Some authors draw comparisons to the Greek myth of the abduction of Persephone as well.テンプレート:Sfn

Monica Otterrmann performed a feminist interpretation of the myth, questioning its interpretation as related to the cycle of nature,テンプレート:Sfn claiming that the narratives represent that Inanna's powers were being restricted by the Mesopotamian patriarchy, due to the fact that, according to her, the region was not conducive to fertility.テンプレート:Sfn Brandão questions this idea in part, for although Inanna's power is at stake in the Sumerian text, in the Akkadian text the goddess' relationship to fertility and fertilization is at stake. Furthermore, in the Sumerian text Inanna's power is not limited by a man, but by another equally powerful goddess, Ereskigal.テンプレート:Sfn

Later myths

Epic of Gilgamesh

テンプレート:Main In the Akkadian Epic of Gilgamesh, Ishtar appears to Gilgamesh after he and his companion Enkidu have returned to Uruk from defeating the ogre Humbaba and demands Gilgamesh to become her consort.テンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Efn Gilgamesh refuses her, pointing out that all of her previous lovers have suffered:テンプレート:Sfn

Infuriated by Gilgamesh's refusal,テンプレート:Sfn Ishtar goes to heaven and tells her father Anu that Gilgamesh has insulted her.テンプレート:Sfn Anu asks her why she is complaining to him instead of confronting Gilgamesh herself.テンプレート:Sfn Ishtar demands that Anu give her the Bull of Heavenテンプレート:Sfn and swears that if he does not give it to her, she will "break in the doors of hell and smash the bolts; there will be confusion [i.e., mixing] of people, those above with those from the lower depths. I shall bring up the dead to eat food like the living; and the hosts of the dead will outnumber the living."[283]

Anu gives Ishtar the Bull of Heaven, and Ishtar sends it to attack Gilgamesh and his friend Enkidu.テンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfn Gilgamesh and Enkidu kill the Bull and offer its heart to the sun-god Shamash.テンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfn While Gilgamesh and Enkidu are resting, Ishtar stands up on the walls of Uruk and curses Gilgamesh.テンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfn Enkidu tears off the Bull's right thigh and throws it in Ishtar's face,テンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfn saying, "If I could lay my hands on you, it is this I should do to you, and lash your entrails to your side."[284] (Enkidu later dies for this impiety.)テンプレート:Sfn Ishtar calls together "the crimped courtesans, prostitutes and harlots"テンプレート:Sfn and orders them to mourn for the Bull of Heaven.テンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfn Meanwhile, Gilgamesh holds a celebration over the Bull of Heaven's defeat.テンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfn

Later in the epic, Utnapishtim tells Gilgamesh the story of the Great Flood,テンプレート:Sfn which was sent by the god Elil to annihilate all life on earth because the humans, who were vastly overpopulated, made too much noise and prevented him from sleeping.テンプレート:Sfn Utnapishtim tells how, when the flood came, Ishtar wept and mourned over the destruction of humanity, alongside the Anunnaki.テンプレート:Sfn Later, after the flood subsides, Utnapishtim makes an offering to the gods.テンプレート:Sfn Ishtar appears to Utnapishtim wearing a lapis lazuli necklace with beads shaped like flies and tells him that Enlil never discussed the flood with any of the other gods.テンプレート:Sfn She swears him that she will never allow Enlil to cause another floodテンプレート:Sfn and declares her lapis lazuli necklace a sign of her oath.テンプレート:Sfn Ishtar invites all the gods except for Enlil to gather around the offering and enjoy.テンプレート:Sfn

Song of Agušaya

The Song of Agušaya,[285] an Akkadian text presumably from the time of Hammurapi, tells a myth mixed with hymnic passages: the war goddess Ištar is filled with constant wrath and plagues the earth with war and battle. With her roar she finally even threatens the wise god Ea in Apsû. He appears before the assembly of gods and decides (similar to Enkidu in the Epic of Gilgameš) to create an equal opponent for Ištar. From the dirt of his fingernails he forms the powerful goddess Ṣaltum ("fight, quarrel"), whom he instructs to confront Ištar disrespectfully and plague her day and night with her roar. The text section with the confrontation of both goddesses is not preserved, but it is followed by a scene in which Ištar demands from Ea to call Ṣaltum back, which he does. Subsequently, Ea establishes a festival in which henceforth a "whirl dance" (gūštû) is to be performed annually in commemoration of the events. The text ends with the statement that Ištar's heart has calmed down.

Other tales

A myth about the childhood of the god Ishum, viewed as a son of Shamash, describes Ishtar seemingly temporarily taking care of him, and possibly expressing annoyance at that situation.テンプレート:Sfn

In a pseudepigraphical Neo-Assyrian text written in the seventh century BCE, but which claims to be the autobiography of Sargon of Akkad,テンプレート:Sfn Ishtar is claimed to have appeared to Sargon "surrounded by a cloud of doves" while he was working as a gardener for Akki, the drawer of the water.テンプレート:Sfn Ishtar then proclaimed Sargon her lover and allowed him to become the ruler of Sumer and Akkad.テンプレート:Sfn

In Hurro-Hittite texts the logogram dISHTAR denotes the goddess Šauška, who was identified with Ishtar in god lists and similar documents as well and influenced the development of the late Assyrian cult of Ishtar of Nineveh according to hittitologist Gary Beckman.テンプレート:Sfn She plays a prominent role in the Hurrian myths of the Kumarbi cycle.テンプレート:Sfn

Later influence

In antiquity

The cult of Inanna/Ishtar may have been introduced to the Kingdom of Judah during the reign of King Manassehテンプレート:Sfn and, although Inanna herself is not directly mentioned in the Bible by name,テンプレート:Sfn the Old Testament contains numerous allusions to her cult.テンプレート:Sfn テンプレート:Bibleverse and テンプレート:Bibleverse mention "the Queen of Heaven", who is probably a syncretism of Inanna/Ishtar and the West Semitic goddess Astarte.テンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfn Jeremiah states that the Queen of Heaven was worshipped by women who baked cakes for her.テンプレート:Sfn

The Song of Songs bears strong similarities to the Sumerian love poems involving Inanna and Dumuzid,テンプレート:Sfn particularly in its usage of natural symbolism to represent the lovers' physicality.テンプレート:Sfn テンプレート:Bibleverse テンプレート:Bibleverse mentions Inanna's husband Dumuzid under his later East Semitic name Tammuz,テンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfn and describes a group of women mourning Tammuz's death while sitting near the north gate of the Temple in Jerusalem.テンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfn Marina Warner (a literary critic rather than Assyriologist) claims that early Christians in the Middle East assimilated elements of Ishtar into the cult of the Virgin Mary.テンプレート:Sfn She argues that the Syrian writers Jacob of Serugh and Romanos the Melodist both wrote laments in which the Virgin Mary describes her compassion for her son at the foot of the cross in deeply personal terms closely resembling Ishtar's laments over the death of Tammuz.テンプレート:Sfn However, broad comparisons between Tammuz and other dying gods are rooted in the work of James George Frazer and are regarded as a relic of less rigorous early 20th century Assyriology by more recent publications.テンプレート:Sfn

The cult of Inanna/Ishtar also heavily influenced the cult of the Phoenician goddess Astarte.テンプレート:Sfn The Phoenicians introduced Astarte to the Greek islands of Cyprus and Cythera,テンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfn where she either gave rise to or heavily influenced the Greek goddess Aphrodite.テンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfn Aphrodite took on Inanna/Ishtar's associations with sexuality and procreation.テンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfn Furthermore, she was known as Ourania (Οὐρανία), which means "heavenly",テンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfn a title corresponding to Inanna's role as the Queen of Heaven.テンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfn

Early artistic and literary portrayals of Aphrodite are extremely similar to Inanna/Ishtar.テンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfn Aphrodite was also a warrior goddess;テンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfn the second-century AD Greek geographer Pausanias records that, in Sparta, Aphrodite was worshipped as Aphrodite Areia, which means "warlike".テンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfn He also mentions that Aphrodite's most ancient cult statues in Sparta and on Cythera showed her bearing arms.テンプレート:Sfnm Modern scholars note that Aphrodite's warrior-goddess aspects appear in the oldest strata of her worshipテンプレート:Sfn and see it as an indication of her Near Eastern origins.テンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfn Aphrodite also absorbed Ishtar's association with doves,テンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfn which were sacrificed to her alone.テンプレート:Sfn The Greek word for "dove" was peristerá,テンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfn which may be derived from the Semitic phrase peraḥ Ištar, meaning "bird of Ishtar".テンプレート:Sfn The myth of Aphrodite and Adonis is derived from the story of Inanna and Dumuzid.テンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfn

Classical scholar Charles Penglase has written that Athena, the Greek goddess of wisdom and war, resembles Inanna's role as a "terrifying warrior goddess".テンプレート:Sfn Others have noted that the birth of Athena from the head of her father Zeus could be derived from Inanna's descent into and return from the Underworld.テンプレート:Sfn However, as noted by Gary Beckman, a rather direct parallel to Athena's birth is found in the Hurrian Kumarbi cycle, where Teshub is born from the surgically split skull of Kumarbi,テンプレート:Sfn rather than in any Inanna myths.

In Mandaean cosmology, one of the names for Venus is ʿStira, which is derived from the name Ishtar.[286]

Anthropologist Kevin Tuite argues that the Georgian goddess Dali was also influenced by Inanna,テンプレート:Sfn noting that both Dali and Inanna were associated with the morning star,テンプレート:Sfn both were characteristically depicted nude,テンプレート:Sfn (but note that Assyriologists assume the "naked goddess" motif in Mesopotamian art in most cases cannot be Ishtar,テンプレート:Sfn and the goddess most consistently depicted as naked was Shala, a weather goddess unrelated to Ishtarテンプレート:Sfn) both were associated with gold jewelry,テンプレート:Sfn both sexually preyed on mortal men,テンプレート:Sfn both were associated with human and animal fertility,テンプレート:Sfn (note however that Assyriologist Dina Katz pointed out the references to fertility are more likely to be connected to Dumuzi than Inanna/Ishtar in at least some casesテンプレート:Sfn) and both had ambiguous natures as sexually attractive, but dangerous, women.テンプレート:Sfn

Traditional Mesopotamian religion began to gradually decline between the third and fifth centuries AD as ethnic Assyrians converted to Christianity. Nonetheless, the cult of Ishtar and Tammuz managed to survive in parts of Upper Mesopotamia.テンプレート:Sfn In the tenth century AD, an Arab traveler wrote that "All the Sabaeans of our time, those of Babylonia as well as those of Harran, lament and weep to this day over Tammuz at a festival which they, more particularly the women, hold in the month of the same name."テンプレート:Sfn

Worship of Venus deities possibly connected to Inanna/Ishtar was known in Pre-Islamic Arabia right up until the Islamic period. Isaac of Antioch (d. 406 AD) says that the Arabs worshipped 'the Star' (kawkabta), also known as Al-Uzza, which many identify with Venus.テンプレート:Sfn Isaac also mentions an Arabian deity named Baltis, which according to Jan Retsö most likely was another designation for Ishtar.テンプレート:Sfn In pre-Islamic Arabian inscriptions themselves, it appears that the deity known as Allat was also a Venusian deity.テンプレート:Sfn Attar, a male god whose name is a cognate of Ishtar's, is a plausible candidate for the role of Arabian Venus deity too on the account of both his name and his epithet "eastern and western."テンプレート:Sfn

Modern relevance

In his 1853 pamphlet The Two Babylons, as part of his argument that Roman Catholicism is actually Babylonian paganism in disguise, Alexander Hislop, a Protestant minister in the Free Church of Scotland, incorrectly argued that the modern English word Easter must be derived from Ishtar due to the phonetic similarity of the two words.テンプレート:Sfn Modern scholars have unanimously rejected Hislop's arguments as erroneous and based on a flawed understanding of Babylonian religion.テンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfn Nonetheless, Hislop's book is still popular among some groups of evangelical Protestantsテンプレート:Sfn and the ideas promoted in it have become widely circulated, especially through the Internet, due to a number of popular Internet memes.テンプレート:Sfn

Ishtar had a major appearance in Ishtar and Izdubar,テンプレート:Sfn a book-length poem written in 1884 by Leonidas Le Cenci Hamilton, an American lawyer and businessman, loosely based on the recently translated Epic of Gilgamesh.テンプレート:Sfn Ishtar and Izdubar expanded the original roughly 3,000 lines of the Epic of Gilgamesh to roughly 6,000 lines of rhyming couplets grouped into forty-eight cantos.テンプレート:Sfn Hamilton significantly altered most of the characters and introduced entirely new episodes not found in the original epic.テンプレート:Sfn Significantly influenced by Edward FitzGerald's Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam and Edwin Arnold's The Light of Asia,テンプレート:Sfn Hamilton's characters dress more like nineteenth-century Turks than ancient Babylonians.テンプレート:Sfn In the poem, Izdubar (the earlier misreading for the name "Gilgamesh") falls in love with Ishtar,テンプレート:Sfn but, then, "with hot and balmy breath, and trembling form aglow", she attempts to seduce him, leading Izdubar to reject her advances.テンプレート:Sfn Several "columns" of the book are devoted to an account of Ishtar's descent into the Underworld.テンプレート:Sfn At the conclusion of the book, Izdubar, now a god, is reconciled with Ishtar in Heaven.テンプレート:Sfn In 1887, the composer Vincent d'Indy wrote Symphony Ishtar, variations symphonique, Op. 42, a symphony inspired by the Assyrian monuments in the British Museum.テンプレート:Sfn

Inanna has become an important figure in modern feminist theory because she appears in the male-dominated Sumerian pantheon,テンプレート:Sfn but is equally as powerful, if not more powerful than, the male deities she appears alongside.テンプレート:Sfn Simone de Beauvoir, in her book The Second Sex (1949), argues that Inanna, along with other powerful female deities from antiquity, have been marginalized by modern culture in favor of male deities.テンプレート:Sfn Tikva Frymer-Kensky has argued that Inanna was a "marginal figure" in Sumerian religion who embodies the "socially unacceptable" archetype of the "undomesticated, unattached woman".テンプレート:Sfn Feminist author Johanna Stuckey has argued against this idea, pointing out Inanna's centrality in Sumerian religion and her broad diversity of powers, neither of which seem to fit the idea that she was in any way regarded as "marginal".テンプレート:Sfn Assyriologist Julia M. Asher-Greve, who specializes in the study of position of women in antiquity, criticizes Frymer-Kensky's studies of Mesopotamian religion as a whole, highlighting the problems with her focus on fertility, the small selection of sources her works relied on, her view that position of goddesses in the pantheon reflected that of ordinary women in society (so-called "mirror theory"), as well as the fact her works do not accurately reflect the complexity of changes of roles of goddesses in religions of ancient Mesopotamia.テンプレート:Sfn Ilona Zsolnay regards Frymer-Kensky's methodology as faulty.テンプレート:Sfn

In Neopaganism and Sumerian reconstructionism

Inanna's name is also used to refer to the Goddess in modern Neopaganism and Wicca.テンプレート:Sfn Her name occurs in the refrain of the "Burning Times Chant",テンプレート:Sfn one of the most widely used Wiccan liturgies.テンプレート:Sfn Inanna's Descent into the Underworld was the inspiration for the "Descent of the Goddess",テンプレート:Sfn one of the most popular texts of Gardnerian Wicca.テンプレート:Sfn

In popular culture

- Features as Gilgamesh's archenemy and a huntress in SMITE (2014) under her Ishtar name.

- Inanna appears as separate and playable Archer-class, Rider-class, and Avenger-class Servants in Fate/Grand Order (2015), under her Ishtar name. Her Avenger-class form is later revealed to be Astarte (stylized in-game as Ashtart), sharing a similar form as Ishtar.

Dates (approximate)

| Historical sources | ||

| Time | Period | Source |

| テンプレート:Circa BCE | Ubaid period | |

| テンプレート:Circa BCE | Uruk period | Uruk vaseテンプレート:Sfn |

| テンプレート:Circa BCE | Early Dynastic period | |

| テンプレート:Circa BCE | Akkadian Empire | writings by Enheduanna:テンプレート:Sfnテンプレート:Sfn Nin-me-šara, "The Exaltation of Inanna" |

| テンプレート:Circa BCE | Gutian Period | |

| テンプレート:Circa BCE | Ur III Period | Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta Gilgamesh, Enkidu, and the Netherworld |

See also

Notes

References

Bibliography

- テンプレート:Cite journal

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Cite journal

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Cite book

- テンプレート:Cite book

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Cite journal

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Cite journal

- テンプレート:Cite journal

- テンプレート:Cite book

- テンプレート:Cite book

- テンプレート:Cite book

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Cite book

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Cite journal

- テンプレート:Cite book

- Enheduanna. The Exaltation of Inanna (Inanna B): Translation.{{{date}}} - via {{{via}}}.

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Wikicite

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Cite journal

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Cite book

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Cite book

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Cite book

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Cite book

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Cite journal

- テンプレート:Cite book

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Cite book

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Cite journal

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Cite journal

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Cite journal

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Cite book

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Cite book

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Cite journal

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Cite book

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Cite journal

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Cite book

- テンプレート:Citation

- The Development, Heyday, and Demise of Panbabylonism.{{{date}}} - via {{{via}}}.

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Cite journal

- テンプレート:Cite book

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Cite book

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Cite book

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Citation

- テンプレート:Cite book

- テンプレート:Cite book

Further reading

- テンプレート:Cite book

- The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature.{{{date}}} - via {{{via}}}.

- テンプレート:Cite encyclopedia

- Sumerian Lexicon Version 3.0.2009 - via {{{via}}}.

- テンプレート:Cite book

External links

- Ancient Mesopotamian Gods and Goddesses: Inana/Ištar (goddess)

- "Documents that Changed the World: The Exaltation of Inanna, 2300 BCE", University of Washington News, 5 May 2015

呼称

その名は「nin-anna」(天の女主人)を意味するとされている[287]。

ウルクにあったイナンナのための神殿/寺院の名は「E-ana」(エアンナ、「天(アヌ)の家」の意味)であった。

イナンナのシュメール語の別名は「nin-edin」(エデンの女主人)、「Inanna-edin」(エデンのイナンナ)であった。彼女の夫であるドゥムジのシュメール語の別名は「{mulu-edin」(エデンの主)であった。

アッカド帝国(Akkadian Empire|en)期には「イシュタル」(新アッシリア語: DINGIR INANNA)と呼ばれた。イシュタルはフェニキアの女神アスタルテやシリアの女神アナトと関連し、古代ギリシアではアプロディーテーと呼ばれ、ローマのヴィーナス(ウェヌス)女神と同一視されている[287]。

神話のなかのイナンナ

系譜

イナンナは系譜上はアンの娘だが、月神ナンナ(シン)の娘とされることもあり、この場合太陽神ウトゥ(シャマシュ)とは双子の兄妹で、冥界の女王エレシュキガルの妹でもある[288]。夫にドゥムジ (メソポタミア神話)(Dumuzid the Shepherd)をいただく。子供は息子シャラ(Shara, Šara, シュメール語: 𒀭𒁈, dšara2, dšara)。別の息子ルラル(Lulal)はウトゥの女祭事(神官)ニンスンの息子ともされている。

エンキの紋章を奪う

メソポタミア神話において、イナンナは知識の神エンキの誘惑をふりきり、酔っ払ったエンキから、文明生活の恵み「メー」(水神であるエンキの持っている神の権力を象徴する紋章)をすべて奪い、エンキの差し向けたガラの悪魔の追跡から逃がれ、ウルクに無事たどりついた[私注 7]。エンキはだまされたことを悟り、最終的に、ウルクとの永遠の講和を受け入れた。この神話は、太初において、政治的権威がエンキの都市エリドゥ(紀元前4900]頃に建設された都市)からイナンナの都市ウルクに移行するという事件(同時に、最高神の地位がエンキからイナンナに移ったこと)を示唆していると考えられる。

イナンナ女神の歌

シュメール時代の粘土板である『イナンナ女神の歌』よりイナンナは、ニンガルから生まれた魅力と美貌を持ち、龍のように速く飛び[289]、南風に乗りアプスーから聖なる力を得た[290]。母親ニンガルの胎内から誕生した際、すでにシタ(cita)とミトゥム(mitum)という2つの鎚矛を手にして生まれた[291]。

イナンナとフルップ(ハルブ)の樹

(出典の明記、2018年2月) ある日、イナンナはぶらぶらとユーフラテス河畔を歩いていると、強い南風にあおられて今にもユーフラテス川に倒れそうな「フルップ(ハルブ)の樹[292]」を見つけた。あたりを見渡しても他の樹木は見あたらず、イナンナはこの樹が世界の領域を表す世界樹(生命の木)であることに気がついた。

そこでイナンナはある計画を思いついた。

この樹から典型的な権力の象徴をつくり、この不思議な樹の力を利用して世界を支配しようと考えたのだ。

イナンナはそれをウルクに持ち帰り、聖なる園(エデン)に植えて大事に育てようとする。

まだ世界はちょうど創造されたばかりで、その世界樹はまだ成るべき大きさには程遠かった。イナンナは、この時すでにフルップの樹が完全に成長した日にはどのような力を彼女が持つことができるかを知っていた。

「もし時が来たらならば、この世界樹を使って輝く王冠と輝くベッド(王座)を作るのだ」

その後10年の間にその樹はぐんぐんと成長していった。

しかし、その時(アン)ズーがやって来て、天まで届こうかというその樹のてっぺんに巣を作り、雛を育て始めた。

さらに樹の根にはヘビが巣を作っていて、樹の幹にはリリスが住処を構えていた。リリスの姿は大気と冥界の神であることを示していたので、イナンナは気が気でなかった。

しばらくの後、いよいよこの樹から支配者の印をつくる時が来た時、リリスにむかって聖なる樹から立ち去るようにお願いした。

しかしながら、イナンナはその時まだ神に対抗できるだけの力を持っておらず、リリスも言うことを聞こうとはしなかった。彼女の天真爛漫な顔はみるみるうちに失望へと変わっていった。そして、このリリスを押しのけられるだけの力を持った神は誰かと考えた。そして彼女の兄弟である太陽神ウトゥに頼んでみることになった。

暁方にウトゥは日々の仕事として通っている道を進んでいる時だった。イナンナは彼に声をかけ、これまでのいきさつを話し、助けを懇願した。ウトゥはイナンナの悩みを解決しようと、銅製の斧をかついでイナンナの聖なる園にやって来た。

ヘビは樹を立ち去ろうとしないばかりかウトゥに襲いかかろうとしたので、彼はそれを退治した。ズーは子供らと高く舞い上がると天の頂きにまで昇り、そこに巣を作ることにした。リリスは自らの住居を破壊し、誰も住んでいない荒野に去っていった。

ウトゥはその後、樹の根っこを引き抜きやすくし、銅製の斧で輝く王冠と輝くベッドをイナンナのために作ってやった。彼女は「他の神々と一緒にいる場所ができた」ととても喜び、感謝の印として、その樹の根と枝を使って「プック(Pukku)とミック(Mikku)」(輪と棒)を作り、ウトゥへの贈り物とした[私注 8]。

なお、この神話には、ウトゥの代わりにギルガメシュが同じ役割として登場するヴァリエーション(変種)がある。

イナンナの冥界下り

天界の女王イナンナは、理由は明らかではないものの(一説にはイナンナは冥界を支配しようと企んでいた)、地上の七つの都市の神殿を手放し、姉のエレシュキガルの治める冥界に下りる決心をした。冥界へむかう前にイナンナは七つのメーをまとい、それを象徴する飾りなどで身を着飾って、忠実な従者であるニンシュブルに自分に万が一のことがあったときのために、力のある神エンリル、ナンナ、エンキに助力を頼むように申しつけた[293][294]。

冥界の門を到着すると、イナンナは門番であるネティに冥界の門を開くように命じ[295]、ネティはエレシュキガルの元に承諾を得に行った。エレシュキガルはイナンナの来訪に怒ったが、イナンナが冥界の七つの門の一つを通過するたびに身につけた飾りの一つをはぎ取ることを条件に通過を許した。イナンナは門を通るごとに身につけたものを取り上げられ、最後の門をくぐるときに全裸になった。彼女はエレシュキガルの宮殿に連れて行かれて、七柱のアヌンナの神々に冥界へ下りた罪を裁かれた。イナンナは死刑判決を受け、エレシュキガルが「死の眼差し」を向けると倒れて死んでしまった。彼女の死体は宮殿の壁に鉤で吊るされた[296][297]。

三日三晩が過ぎ[298]、ニンシュブルは最初にエンリル、次にナンナに経緯を伝えて助けを求めたが、彼らは助力を拒んだ。しかしエンキは自分の爪の垢からクルガルラ(泣き女)とガラトゥル(哀歌を歌う神官)という者を造り、それぞれに「命の食べ物」と「命の水」を持って、先ずエレシュキガルの下へ赴き、病んでいる彼女を癒すよう、そしてその礼として彼女が与えようとする川の水と大麦は受け取らずにイナンナの死体を貰い受け、死体に「命の食べ物」と「命の水」を振りかけるように命じた。クルガルラとガラトゥルがエンキに命じられた通りにするとイナンナは起き上がった。しかし冥界の神々はイナンナが地上に戻るには身代わりに誰かを冥界に送らなければならないという条件をつけ、ガルラという精霊たちが彼女に付いて行った[299][300]。

まず、イナンナはニンシュブルに会った。ガルラたちは彼女を連れて行こうとしたが、イナンナは彼女が自分のために手を尽くしたことと喪に服してくれたことを理由に押しとどめた。次にシャラ神、さらにラタラク神に会うが、彼らも喪に服し、イナンナが生還したことを地に伏して喜んだため、彼らが自身に仕える者であることを理由に連れて行くことを許さなかった。しかし夫の神ドゥムジが喪にも服さず着飾っていたため、イナンナは怒り、彼を自分の身代わりに連れて行くように命じた。ドゥムジはイナンナの兄ウトゥに救いを求め、憐れんだウトゥは彼の姿を蛇に変えた。ドゥムジは姉のゲシュティンアンナの下へ逃げ込んだが、最後には羊小屋にいるところを見つかり、地下の世界へと連れ去られた。その後、彼と姉が半年ずつ交代で冥界に下ることになった[301][302]。

王権を授与する神としてのイナンナ

イナンナ神は外敵を排撃する神としてイメージされており、統一国家形成期には王権を授与する神としてとらえられている。なお、それに先だつ領域国家の時代、および後続する統一国家確立期においては王権を授与する神はエンリル(シュメール語: 𒀭𒂗𒇸)であり、そこには交代がみられる[303]。

ウルクの大杯

高さ1m強、石灰岩で造られた大杯。ドイツ隊によって発見され、イラク博物館に展示されていた[304]。最上段には都市の支配者が最高神イナンナに献納品を携え訪れている図像が描かれ、最下段にはチグリスとユーフラテスが、その上に主要作物、羊のペア、さらに逆方向を向く裸の男たちが描かれている[305]。図像はイナンナとドゥムジの「聖婚」を示し、当時の人々が豊穣を願う性的合一の儀式を国家祭儀にまで高めていた様子を教えている[306]。

私的解説

イナンナが時に裸体で描かれることは、「黄泉の国での姿」を暗示しているといえようか。(正常とは逆の姿、ということで)

参考文献

- Wikipedia:イナンナ(最終閲覧日:22-12-08)

- 前田徹『メソポタミアの王・神・世界観-シュメール人の王権観-』山川出版社、2003年10月。ISBN 4-634-64900-4

- 矢島文夫『メソポタミアの神話』筑摩書房、1982年、7月。

- 岡田明子・小林登志子『シュメル神話の世界 -粘土板に刻まれた最古のロマン』〈中公新書 1977〉2008年12月。ISBN 978-4-12-101977-6

関連項目

私的注釈

参照

- ↑ Wolkstein, Kramer, 1983, pages92, 193

- ↑ Heffron, 2016

- ↑ Sumerian dictionary, http://oracc.iaas.upenn.edu/epsd2/cbd/sux/N.html , oracc.iaas.upenn.edu

- ↑ Heffron, 2016

- ↑ Wolkstein, Kramer, 1983, pagexviii

- ↑ Nemet-Nejat, 1998, page182

- ↑ Wolkstein, Kramer, 1983, pagexv

- ↑ Penglase, 1994, pages42–43

- ↑ Kramer, 1961, page101

- ↑ Wiggermann, 1999, p216

- ↑ Leick, 1998, p87, Black Green, 1992, p108, Wolkstein Kramer, 1983, pxviii, Collins, 1994, p110-111, Brandão, 2019, p43

- ↑ Leick, 1998, p87, Black Green, 1992, p108, Wolkstein Kramer, 1983, pxviii, xv, Collins, 1994, p=110-111

- ↑ Brandão, 2019, p65

- ↑ Leick, 1998, page86

- ↑ Harris, 1991, pages261–278

- ↑ Harris, 1991, pages261–278

- ↑ Leick, 1998, page86

- ↑ Wolkstein, Kramer, 1983, pagesxiii–xix

- ↑ Harris, 1991, pages261–278

- ↑ Rubio, 1999, pages1–16

- ↑ Collins, 1994, page110

- ↑ Leick, 1998, page96

- ↑ Collins, 1994, page110

- ↑ Leick, 1998, page96

- ↑ Collins, 1994, page110

- ↑ Collins, 1994, page110

- ↑ Collins, 1994, pages110–111

- ↑ Collins, 1994, pages110–111

- ↑ Meador, Betty De Shong (2000). Inanna, Lady of Largest Heart: Poems of the Sumerian High Priestess Enheduanna. University of Texas Press. pp. 14–15. ISBN 978-0-292-75242-9.

- ↑ Site officiel du musée du Louvre, http://cartelfr.louvre.fr/cartelfr/visite?srv=car_not_frame&idNotice=9643 , cartelfr.louvre.fr

- ↑ Vanstiphout, 1984, pages225–228

- ↑ Vanstiphout, 1984, page228

- ↑ Vanstiphout, 1984, page228

- ↑ Brandão, 2019, p43

- ↑ Vanstiphout, 1984, pages228–229

- ↑ Black, Green, 1992, page108

- ↑ Black, Green, 1992, page108

- ↑ Suter, 2014, page551

- ↑ Suter, 2014, pages550–552

- ↑ Suter, 2014, pages550–552

- ↑ Suter, 2014, pages552–554

- ↑ Van der Mierop, 2007, page55

- ↑ Van der Mierop, 2007, page55

- ↑ Van der Mierop, 2007, page55

- ↑ Van der Mierop, 2007, page55

- ↑ Maeda, 1981, p8

- ↑ Leick, 1998, page87

- ↑ Collins, 1994, pages110–111

- ↑ Leick, 1998, page87

- ↑ Collins, 1994, page111

- ↑ Leick, 1998, page87

- ↑ Leick, 1998, page87

- ↑ Black, Green, 1992, page108

- ↑ Wolkstein, Kramer, 1983, pages=xviii, xv

- ↑ A. Archi, The Gods of Ebla [in:] J. Eidem, C.H. van Zoest (eds.), Annual Report NINO and NIT 2010, 2011, p. 3

- ↑ Leick, 1998, page87

- ↑ Asher-Greve Westenholz, 2013, p27, Kramer, 1961, p101, Wolkstein Kramer, 1983, pxiii–xix, Nemet-Nejat, 1998, p182

- ↑ Leick, 1998, page87

- ↑ Leick, 1998, page87

- ↑ Black, Green, 1992, pages108–109

- ↑ Harris, 1991, pages261–278

- ↑ modern-day Warka, Biblical Erech

- ↑ é-an-na means "sanctuary" ("house" + "Heaven" ["An"] + genitive)(Halloran, 2009)

- ↑ Harris, 1991, pages261–278

- ↑ Harris, 1991, pages261–278

- ↑ Asher-Greve, Westenholz, 2013, p42

- ↑ Asher-Greve, Westenholz, 2013, p42

- ↑ Asher-Greve, Westenholz, 2013, p50

- ↑ Asher-Greve, Westenho, z, 2013, p62

- ↑ Asher-Greve, Westenholz, 2013, p62

- ↑ Asher-Greve, Westenholz, 2013, p62

- ↑ Leick, 1998, page87

- ↑ Asher-Greve, Westenholz, 2013, p172

- ↑ Asher-Greve, Westenholz, 2013, p79

- ↑ Asher-Greve, Westenholz, 2013, p21

- ↑ Black, Green, 1992, page99

- ↑ Guirand, 1968, page58

- ↑ Black, Green, 1992, page99

- ↑ Asher-Greve, Westenholz, 2013, p20

- ↑ Leick, 2013, pages157–158

- ↑ Leick, 2013, page285

- ↑ Roscoe, Murray, 1997, page65

- ↑ Roscoe, Murray, 1997, pages65–66

- ↑ Roscoe, Murray, 1997, pages65–66

- ↑ Leick, 2013, pages158–163

- ↑ Roscoe, Murray, 1997, page66

- ↑ Brandão, 2019, p63

- ↑ Kramer, 1970

- ↑ Nemet-Nejat, 1998, page196

- ↑ Brandão, 2019, p56

- ↑ Pryke, 2017, pages128–129

- ↑ George, 2006, page6

- ↑ Pryke, 2017, pages128–129

- ↑ Pryke, 2017, page129

- ↑ Day, 2004, p15–17, Marcovich, 1996, p49, Guirand, 1968, p58, Nemet-Nejat, 1998, p193

- ↑ Assante, 2003, p14–47, Day, 2004, p2–21, Sweet, 1994, p85–104, Pryke, 2017, p61

- ↑ Marcovich, 1996, page49

- ↑ Day, 2004, pages2–21

- ↑ Sweet, 1994, pages85–104

- ↑ Assante, 2003, pages14–47

- ↑ Ackerman, 2006, pages116–117

- ↑ Ackerman, 2006, page115

- ↑ Ackerman, 2006, page115

- ↑ Black, Green, 1992, pp156, 169–170

- ↑ Liungman, 2004, page228

- ↑ Black, Green, 1992, pp156, 169–170

- ↑ Liungman, 2004, page228

- ↑ Black, Green, 1992, page170

- ↑ Black, Green, 1992, pages169–170

- ↑ Black, Green, 1992, pages169–170

- ↑ Black, Green, 1992, page170

- ↑ Black, Green, 1992, page170

- ↑ Nemet-Nejat, 1998, pages193–194

- ↑ Liungman, 2004, page228

- ↑ Jacobsen, 1976

- ↑ Black, Green, 1992, page156

- ↑ Black, Green, 1992, pages156–157

- ↑ Black, Green, 1992, page156

- ↑ Black, Green, 1992, page118

- ↑ Collins, 1994, pages113–114

- ↑ Black, Green, 1992, page118

- ↑ Collins, 1994, pages113–114

- ↑ Collins, 1994, pages113–114

- ↑ Black, Green, 1992, pp119

- ↑ Lewis, Llewellyn-Jones, 2018, page=335

- ↑ Botterweck, Ringgren, 1990, page35

- ↑ Botterweck, Ringgren, 1990, page35

- ↑ Botterweck, Ringgren, 1990, page35

- ↑ Lewis, Llewellyn-Jones, 2018, page335

- ↑ Lewis, Llewellyn-Jones, 2018, page335

- ↑ Black, Green, 1992, pages108–109,

- ↑ Nemet-Nejat, 1998, page203

- ↑ Black, Green, 1992, pages108–109

- ↑ Cooley, 2008, pages161–172

- ↑ Cooley, 2008, pages161–172

- ↑ Cooley, 2008, pages161–172

- ↑ Cooley, 2008, pages161–172

- ↑ Cooley, 2008, pages163–164

- ↑ Cooley, 2008, pages161–172

- ↑ Cooley, 2008, pages161–172

- ↑ Cooley, 2008, pages161–172

- ↑ Cooley, 2008, pages161–172

- ↑ Cooley, 2008, pages161–172

- ↑ Caton, 2012

- ↑ Meyer, n.d.

- ↑ Foxvog, 1993, page106

- ↑ Black, Green, 1992, pages34–35

- ↑ Foxvog, 1993, page106

- ↑ Black, Green, 1992, page108

- ↑ Vanstiphout, 1984, pages225–228

- ↑ Penglase, 1994, pages15–17

- ↑ Vanstiphout, 1984, pages225–228

- ↑ Penglase, 1994, pages15–17

- ↑ Black, Green, 1992, pp108–9

- ↑ Leick, 2013, pages65–66

- ↑ George, 2015, p8

- ↑ Asher-Greve, Westenholz, 2013, p140, " Asher-Greve 2003; cf. Groneberg (1986a: 45) argues that Inana is significant because she is not a mother goddess [...]"

- ↑ Asher-Greve Julia M., Joan Goodnick Westenholz, Images, Orbis Biblicus et Orientalis: 259, Goddesses in Context: On Divine Powers, Roles, Relationships and Gender in Mesopotamian Textual and Visual Sources, 2013, https://www.zora.uzh.ch/id/eprint/135436/1/Asher-Greve_Westenholz_2013_Goddesses_in_Context.pdf, Fribourg, Academic Press, 2013, page242, isbn:9783525543825, 26 August 2022

『グラハム・カニンガム (1997: 171)によれば、呪文は「象徴的同一性の形式」と関係があり、いくつかの女神との象徴的同一性は、例えば[...]イナナとナナヤとのセックスと愛に関する事項[...]など、その神の機能または領域に関係していることは明らかであるように思われる。』 - ↑ Black, Green, 1992, pp108–9

- ↑ Gilgamesh, p. 86

- ↑ Pryke, 2017, page146

- ↑ Katz, 1996, p93-103

- ↑ Katz, 2015, p67-68

- ↑ Black, Green, 1992, pages108–109

- ↑ Vanstiphout, 1984, pages226–227

- ↑ Enheduanna pre 2250 BCE A hymn to Inana (Inana C), id:4.07.3, 2003, The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature, http://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/cgi-bin/etcsl.cgi?text=t.4.07.3#, at:=lines 18–28, ETCSL 4.07.3

- ↑ Vanstiphout, 1984, page227

- ↑ Asher-Greve, Westenholz, 2013, p203-204

- ↑ Westenholz, 1997, p78

- ↑ Wiggermann, 1999a, p369, 371

- ↑ Wiggermann, 1997, p42

- ↑ Streck, Wasserman, 2013, p184

- ↑ Asher-Greve, Westenholz, 2013, p113-114

- ↑ Asher-Greve, Westenholz, 2013, p71

- ↑ Asher-Greve, Westenholz, 2013, |p286

- ↑ Zsolnay, 2010, p397-401

- ↑ Zsolnay, 2010, p393

- ↑ Asher-Greve, Westenholz, 2013, p17

- ↑ Beckman, 1999, p25

- ↑ Asher-Greve, Westenholz, 2013, p127

- ↑ Asher-Greve, Westenholzm, 2013, p116-117

- ↑ Zsolnay, 2010, p401

- ↑ Black, Green, 1992, pages108, 182

- ↑ Wolkstein, Kramer, 1983, pagesx–xi

- ↑ Pryke, 2017, page36

- ↑ Pryke, 2017, pages36–37

- ↑ Pryke, 2017, pages36–37

- ↑ Black, Green, 1992, page183

- ↑ Black, Green, 1992, page77

- ↑ Pryke, 2017, page108

- ↑ Pryke, 2017, page108

- ↑ Wiggermann, 1997, p47-48

- ↑ Schwemer, 2007, p157

- ↑ Asher-Greve, Westenholz, 2013, p230

- ↑ Wilcke, 1980, p80

- ↑ Asher-Greve, Westenholz, 2013, p45

- ↑ Asher-Greve, Westenholz, 2013, p75

- ↑ Asher-Greve, Westenholz, 2013, p116

- ↑ Beckman, 2002, p37

- ↑ Black, Green, 1992, page108

- ↑ Leick, 1998, page88

- ↑ Brandão, 2019, pp47, 74

- ↑ Wilcke, 1980, p80

- ↑ Black, Green, 1992, page108

- ↑ Leick, 1998, page88

- ↑ Brandão, 2019, p74

- ↑ Asher-Greve Julia M., Asher-Greve Julia M., Westenholz Joan Goodnick, Joan Goodnick Westenholz, Facets of Change, Orbis Biblicus et Orientalis: 259, Goddesses in Context: On Divine Powers, Roles, Relationships and Gender in Mesopotamian Textual and Visual Sources, 2013, https://www.zora.uzh.ch/id/eprint/135436/1/Asher-Greve_Westenholz_2013_Goddesses_in_Context.pdf, Fribourg, Academic Press, 2013, page140, isbn:9783525543825, access-date:26 August 2022

- ↑ Wolkstein, Kramer, 1983, pagesx–xi

- ↑ Black, Green, 1992, page108

- ↑ Wolkstein, Kramer, 1983, pages71–84

- ↑ Leick, 1998, page93

- ↑ Wolkstein, Kramer, 1983, page89

- ↑ Leick, 1998, page93

- ↑ Katz, 2015, p67-68

- ↑ Katz, 1996, p93-103

- ↑ Peterson, 2010, p253

- ↑ Asher-Greve, Westenholz, 2013, p80

- ↑ Asher-Greve, Westenholz, 2013, p78

- ↑ Asher-Greve, Westenholz, 2013, p38

- ↑ Asher-Greve, Westenholz, 2013, p78

- ↑ Black, Green, 1992, page108

- ↑ Black, Green, 1992, page173

- ↑ Hallo, 2010, page233

- ↑ Hallo, 2010, page233

- ↑ Lambert, 1987, p163-164

- ↑ Drewnowska-Rymarz, 2008, p30

- ↑ Pryke, 2017, page94

- ↑ Pryke, 2017, page94

- ↑ Wiggermann, 1988, p228-229

- ↑ Wiggermann, 1988, p228-229

- ↑ Wiggermann, 2010, p417

- ↑ Stol, 1998, p146

- ↑ Beckman, 2002, p37-38

- ↑ Stol, 1998, p146

- ↑ Drewnowska-Rymarz, 2008, p23

- ↑ Asher-Greve, Westenholz, 2013, p62

- ↑ Asher-Greve, Westenholz, 2013, p109

- ↑ Asher-Greve, Westenholz, 2013, p48

- ↑ Asher-Greve, Westenholz, 2013, p100

- ↑ Behrens, Klein, 1998, p345

- ↑ Litke, 1998, p148

- ↑ Beckman, 1999, p26

- ↑ Beckman, 2002, p37

- ↑ Beckman, 1998, p4

- ↑ Asher-Greve, Westenholz, 2013, p110-111

- ↑ Potts, 2010, p487

- ↑ Smith, 2014, p35

- ↑ Smith, 2014, p36

- ↑ Smith, 2014, p39, 74-75

- ↑ Asher-Greve, Westenholz, 2013, p134

- ↑ Murat, 2009, p176

- ↑ Wiggermann, 2010, p417

- ↑ Murat, 2009, p176

- ↑ Taracha, 2009, p124, 128

- ↑ Wiggermann, 2010, p417

- ↑ Asher-Greve, Westenholz, 2013, p282

- ↑ Asher-Greve, Westenholz, 2013, p92

- ↑ Asher-Greve, Westenholz, 2013, p116-117; 120

- ↑ Behrens, Klein, 1998, p343-345

- ↑ Asher-Greve, Westenholz, 2013, p86

- ↑ Asher-Greve, Westenholz, 2013, p86

- ↑ Asher-Greve, Westenholz, 2013, p86

- ↑ Asher-Greve, Westenholz, 2013, p270

- ↑ Asher-Greve, Westenholz, 2013, p92-93

- ↑ Heimpel, 1998, p487-488

- ↑ Asher-Greve, Westenholz, 2013, p86

- ↑ Beckman, 1999, p27

- ↑ Beckman, 2002, p37-39

- ↑ Abdi, 2017, p10

- ↑ Henkelman, 2008, p266

- ↑ Beckman, 1999, p25-27

- ↑ Beckman, 1998, p1-3

- ↑ Beckman, 1998, p7-8

- ↑ rantz-Szabó, 1983, p304

- ↑ Wilhelm, 1989, p52

- ↑ Wiggins, 2007, p156

- ↑ Wiggins, 2007, p156

- ↑ Wiggins, 2007, p156

- ↑ Wiggins, 2007, p156-163

- ↑ Wiggins, 2007, p169

- ↑ Kramer, 1963, pages172–174

- ↑ CDLI Tablet P346140.{{{date}}} - via {{{via}}}.

- ↑ Gilgamesh, p. 87

- ↑ Gilgamesh, p. 88

- ↑ Foster, Benjamin R. (20053), Before the Muses. An Anthology of Akkadian Literature, Bethesda, pp. 96-106. SEAL: VS 10, 214 (Agušaya A) SEAL: RA 15, 159ff. (Agušaya B)

- ↑ テンプレート:Cite book

- ↑ 287.0 287.1 アンソニー・グリーン監修『メソポタミアの神々と空想動物』p.24、山川出版社、2012/07

- ↑ アンソニー・グリーン監修『メソポタミアの神々と空想動物』p.25、山川出版社、2012/07

- ↑ 「イナンナ女神の歌」1-4

- ↑ 「イナンナ女神の歌」5-8

- ↑ 「イナンナ女神の歌」9-12

- ↑ [Hulupp]-アッカド語で「生命の木」のこと。

- ↑ 矢島、51 - 52頁。

- ↑ 岡田・小林、163頁。

- ↑ 来訪の理由を問われ、エレシュキガルの夫グアガルアンナの葬儀に出席することを口実にしたともされる(岡田・小林、163頁)。

- ↑ 矢島。52 - 56頁

- ↑ 岡田・小林、164。

- ↑ 異聞では七年七ヶ月七日とも七年ともいわれる(岡田・小林、167頁)。

- ↑ 矢島、56 - 58頁

- ↑ 岡田・小林、164 - 165頁、但し、こちらではエレシュキガルの病を癒すこと、その礼としてイナンナの死体を求めることについての記載は無い。

- ↑ 矢島、58 - 62頁。

- ↑ 岡田・小林、165 -166頁。

- ↑ 前田(2003)p.21

- ↑ 前川和也『図説メソポタミア文明』p.6

- ↑ 前川和也『図説メソポタミア文明』p.8

- ↑ 前川和也『図説メソポタミア文明』p.9