アンズー

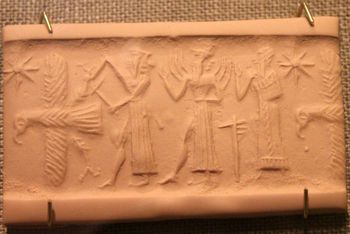

アンズー(Anzû)は、ズー(Zū、dZû)あるいはImdugud(シュメール語:𒀭𒅎𒂂、 AN.IM.DUGUDMUŠEN)としても知られている、メソポタミア神話に登場する怪物である。現在ではアンズー(Anzū)がより正確な呼称であるとされる。巨大な鳥や、ライオンの頭を持つワシの姿で表されることがある(グリフォンを参照)。

ズーはアプスーの淡水と広い大地から生まれたとも、女神シリスの息子ともいわれる。 [1][2]

天の主神エンリルの随獣であり彼に仕えていたが、主神権の簒奪を目論み、その象徴である「天命の書版(Tablet of Destinies (mythic item))」を盗み出してしまう。この話はいくつかバージョンがあり、あるバージョンでは、「天命の書板」を取り返すために神々がルガルバンダを送り込み、彼がズーを殺したことになっており(要出典、2018年2月)、また別のバージョンでは、エアとベレト・イリがニヌルタを書板の奪還に向かわせたという。また、アッシュールバニパルの讃歌では、マルドゥクがズーの討伐を命じられている。

Anzû, also known as dZû and (Sumerian: テンプレート:Script), is a lesser divinity or monster in several Mesopotamian religions. He was conceived by the pure waters of the Apsu and the wide Earth, or as son of Siris. Anzû was depicted as a massive bird who can breathe fire and water, although Anzû is alternately depicted as a lion-headed eagle.

Stephanie Dalley, in Myths from Mesopotamia, writes that "the Epic of Anzu is principally known in two versions: an Old Babylonian version of the early second millennium [BC], giving the hero as Ningirsu; and 'The Standard Babylonian' version, dating to the first millennium BC, which appears to be the most quoted version, with the hero as Ninurta". However, the Anzu character does not appear as often in some other writings, as noted below.

Name

The name of the mythological being usually called Anzû was actually written in the oldest Sumerian cuneiform texts as テンプレート:Script (AN.IM.MIMUŠEN; the cuneiform sign 𒄷, or MUŠEN, in context is an ideogram for "bird"). In texts of the Old Babylonian period, the name is more often found as テンプレート:Script AN.IM.DUGUDMUŠEN.[3] In 1961, Landsberger argued that this name should be read as "Anzu", and most researchers have followed suit. In 1989, Thorkild Jacobsen noted that the original reading of the cuneiform signs as written (giving the name "dIM.dugud") is also valid, and was probably the original pronunciation of the name, with Anzu derived from an early phonetic variant. Similar phonetic changes happened to parallel terms, such as imdugud (meaning "heavy wind") becoming ansuk. Changes like these occurred by evolution of the im to an (a common phonetic change) and the blending of the new n with the following d, which was aspirated as dh, a sound which was borrowed into Akkadian as z or s.[4]

It has also been argued based on contextual evidence and transliterations on cuneiform learning tablets, that the earliest, Sumerian form of the name was at least sometimes also pronounced Zu, and that Anzu is primarily the Akkadian form of the name. However, there is evidence for both readings of the name in both languages, and the issue is confused further by the fact that the prefix 𒀭 (AN) was often used to distinguish deities or even simply high places. AN.ZU could therefore mean simply "heavenly eagle".[3]

Origin and cultural evolution

Thorkild Jacobsen proposed that Anzu was an early form of the god Abu, who was also syncretized by the ancients with Ninurta/Ningirsu, a god associated with thunderstorms. Abu was referred to as "Father Pasture", illustrating the connection between rainstorms and the fields growing in Spring. According to Jacobsen, this god was originally envisioned as a huge black thundercloud in the shape of an eagle, and was later depicted with a lion's head to connect it to the roar of thunder. Some depictions of Anzu therefore depict the god alongside goats (which, like thunderclouds, were associated with mountains in the ancient Near East) and leafy boughs. The connection between Anzu and Abu is further reinforced by a statue found in the Tell Asmar Hoard depicting a human figure with large eyes, with an Anzu bird carved on the base. It is likely that this depicts Anzu in his symbolic or earthly form as the Anzu-bird, and in his higher, human-like divine form as Abu. Though some scholars have proposed that the statue actually represents a human worshiper of Anzu, others have pointed out that it does not fit the usual depiction of Sumerian worshipers, but instead matches similar statues of gods in human form with their more abstract form or their symbols carved onto the base.[4]

Sumerian and Akkadian myth

In Sumerian and Akkadian mythology, Anzû is a divine storm-bird and the personification of the southern wind and the thunder clouds.[5] This demon—half man and half bird—stole the "Tablet of Destinies" from Enlil and hid them on a mountaintop. Anu ordered the other gods to retrieve the tablet, even though they all feared the demon. According to one text, Marduk killed the bird; in another, it died through the arrows of the god Ninurta.[6]

Anzu also appears in the story of "Inanna and the Huluppu Tree",[7] which is recorded in the preamble to the Sumerian epic poem Gilgamesh, Enkidu, and the Netherworld.[8]

Anzu appears in the Sumerian Lugalbanda and the Anzud Bird (also called: The Return of Lugalbanda).

Babylonian and Assyrian myth

The shorter Old Babylonian version was found at Susa. Full version in Myths from Mesopotamia: Creation, The Flood, Gilgamesh, and Others by Stephanie Dalley, page 222[9] and at The Epic of Anzû, Old Babylonian version from Susa, Tablet II, lines 1-83, read by Claus Wilcke.[10] The longer Late Assyrian version from Nineveh is most commonly called The Myth of Anzu. (Full version in Dalley, page 205).[11] An edited version is at Myth of Anzu.[12]

Also in Babylonian myth, Anzû is a deity associated with cosmogeny. Anzû is represented as stripping the father of the gods of umsimi (which is usually translated "crown" but in this case, as it was on the seat of Bel, it refers to the "ideal creative organ").[13][14] Regarding this, Charles Penglase writes that "Ham is the Chaldean Anzû, and both are cursed for the same allegorically described crime," which parallels the mutilation of Uranus by Cronus and of Osiris by Set.[1]

See also

- Anzu wyliei, a theropod dinosaur named for Anzû

- Asakku, similar Mesopotamian deity

- Griffin or griffon, lion-bird hybrid

- Lamassu, Assyrian deity, bull/lion-eagle-human hybrid

- Tengu, Japanese magical creature half-man half-bird

- Hybrid creatures in mythology

- List of hybrid creatures in mythology

- Tiamat

- Ziz, giant griffin-like bird in Jewish mythology

- Zeus, Greek deity of sky and thunder

- Zuism, Icelander protest against tax for religion

External links

テンプレート:Commons category テンプレート:Wikiquote

- Zu on Encyclopædia Britannica

- テンプレート:Cite book

- The Assyro-Babylonian Mythology FAQ: Anzû

- ETCSL glossary showing Zu as the verb 'to know'

- Myth of Anzu

- Ninurta's return to Nibru: a šir-gida to Ninurta and The Return of Ninurta to Nippur

- Ninurta and the Turtle and Ninurta and the Turtle, or Ninurta and Enki

- Ninurta's exploits and The Exploits of Ninurta, or Lugal-e

- Lugalbanda and the Anzud bird

- The Epic of Anzû, Old Babylonian version from Susa, Tablet II, lines 1-83, read by Claus Wilcke

名前

アンズーと呼ばれる神話上の生物は、最古のシュメールの楔形文字のテキストでは𒀭𒉎𒈪𒄷 (AN.IM.MIMUŠEN)と表記される。(楔形文字𒄷またはMUŠENは、文脈上「鳥」の表意文字)。古バビロニア時代のテキストでは、アンズーの名は𒀭𒉎𒂂𒄷}(AN.IM.DUGUDMUŠEN)としてより頻繁に見られる。 [3]

楔形文字の学習用書版に基づけば、最も初期のシュメール語では少なくとも時々Zuと発音され、Anzuは主にアッカド語の名であると主張される。ただし、両方の言語でどちらの名も読み取ることができ、接頭辞𒀭( AN )が神や単に高い場所を区別するためによく使用されたため、問題はさらに複雑になっている。アンズーは単に「天国のワシ」を意味する可能性もある。 [3]

起源と変化

トーキル・ヤコブセンは、アンズーはアブ神(Abu (god))の初期の形態であり、雷雨に関連する神であるニヌルタ/ニンギルスと習合された説を唱えた。アブは植物の神とされ、暴風雨と春に芽吹く大地のつながりを表した。ヤコブセンによれば、この神はもともと鷲の形をした巨大な黒い雷雲として想像されていたが、後に雷の轟音のイメージからライオンの頭で描かれた。アンズーは時折、山羊(古代近東では山と雷雲が関連付けられた)や葉の生い茂る枝の姿で神と共に描かれた。

アンズーとアブ神のつながりは、テル・アスマル・ホード(Tell Asmar Hoard)で見つかった、台座にアンズー鳥が彫られた大きな目をもつ人物像の遺物によってより強調された。アンズーを人物の象徴的モチーフとして、あるいは初期の姿として用いているとも考えられ、より高次な人間に近い神の姿でアブ神を描いている可能性がある。一部の学者はこの像はアンズーを崇拝する人間を表す説を出しているが、他の学者はそれがシュメールの崇拝者の通常の描写と適合せず、むしろ同様の人型をした神の像や台座に刻まれるシンボルに近いと指摘した。 [4]

グデア王の時代、ラガシュ市においては霊鳥として扱われ、ニンギルス神の象徴だったとされる。ラガシュではアンズーはしばしばライオンを足元に従えた姿で表され、アンズーがエンリル神、ライオンがニンギルス神を象徴したとも考えられている。[15]

ズーが登場する神話

- "Lugalbanda and the Anzud Bird"(『ルガルバンダとアンズー鳥(Lugalbanda and the Anzud Bird)』/『ルガルバンダの帰還』) - 『ルガルバンダ叙事詩』の第二部。王子を助ける霊鳥として登場する。

- "Inanna and the Huluppu Tree"(『イナンナとフルップの樹』) - 『ギルガメシュとエンキドゥと冥界』[16]の前文に記録される物語。女神イナンナのフルップ(ハルブ)の樹に巣食う迷惑者として登場。ギルガメシュによって追い払われる。

- "Lugal-e"(『ルガル神話(Lugal-e)』/『ルガル・エ』)- 悪霊アサグにつく「十一の勇士ども」の一人として登場するがニヌルタ神に殺された。

- "Ninurta and the turtle"(『ニンウルタ神と亀』/『ニンウルタ神の傲慢と処罰』) - アンズーの雛が「メ」と「天命の粘土板」をもつものとして登場。ニンウルタをアブズーに導く。

- "Angim dimma"(『アンギン神話』/『ニンウルタ神のニップル市への凱旋』) - 『ルガル神話』同様、勇士のひとりとして登場。ハルブ・ハランの木にいることになっている。

- "Anzû myth"(『アンズー鳥神話』) - 「天命の書版」を盗みニヌルタ神に退治される怪鳥として登場。

関連項目

参考文献

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Charles Penglase, Greek Myths and Mesopotamia: Parallels and Influence in the Homeric Hymns and Hesiod, https://books.google.com/books?id=c5gYl1px7PcC%7Cdate=4 October 2003, aylor & Francis, isbn:978-0-203-44391-0

- ↑ Charles Penglase, Greek Myths and Mesopotamia: Parallels and Influence in the Homeric Hymns and Hesiod, https://books.google.com/books?id=c5gYl1px7PcC, 4 October 2003, Taylor & Francis, isbn:978-0-203-44391-0

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Alster, B. (1991). Contributions to the Sumerian lexicon. Revue d'Assyriologie et d'archéologie orientale, 85(1): 1-11.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Jacobsen, T. (1989). God or Worshipper. pp. 125-130 in Holland, T.H. (ed.), Studies In Ancient Oriental Civilization no. 47. The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago.

- ↑ テンプレート:Cite book

- ↑ Theft of Destiny.{{{date}}} - via {{{via}}}.

- ↑ Myth of the Huluppu Tree.{{{date}}} - via {{{via}}}.

- ↑ The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature.{{{date}}} - via {{{via}}}.

- ↑ テンプレート:Cite book

- ↑ The Epic of Anzû, Old Babylonian version from Susa, Tablet II: BAPLAR.{{{date}}} - via {{{via}}}.

- ↑ テンプレート:Cite book

- ↑ Myth of Anzu.{{{date}}} - via {{{via}}}.

- ↑ テンプレート:Cite book

- ↑ テンプレート:Cite book "The Sin of the God Zu" at "Sacred Texts" website.

- ↑ シュメル神話の世界, 岡田明子・小林登志子, 2008, 中央公論新社, 中公新書, isbn:9784121019776, 288ページ

- ↑ http://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/cgi-bin/etcsl.cgi?text=t.1.8.1.4&charenc=j#, The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature, 2015-03-24, https://web.archive.org/web/20120402155323/http://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/cgi-bin/etcsl.cgi?text=t.1.8.1.4&charenc=j, 2012-04-02