「アンズー」の版間の差分

| (同じ利用者による、間の44版が非表示) | |||

| 1行目: | 1行目: | ||

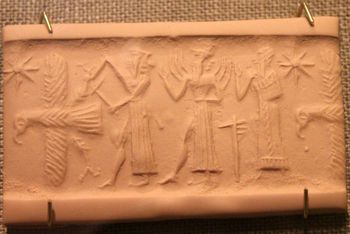

| − | [[画像:Relief Im-dugud Louvre AO2783.jpg|thumb|350px|right| | + | [[画像:Relief Im-dugud Louvre AO2783.jpg|thumb|350px|right|単頭のライオン頭の鷲「ズー(アンズー)」。紀元前2550年~2500年。ラガシュの王ウル=ナンシェのアラバスター製奉納レリーフ(「動物の支配者」をモチーフにした獅子頭の鷲のアンズーを表現)、ギルスの古代都市テルで発見、ルーブル美術館蔵]] |

[[画像:Sumerian Status from Tell Asmar, part of the Tell Asmar Hoard.jpeg|thumb|350px|right|男女の礼拝者(イラク博物館)]] | [[画像:Sumerian Status from Tell Asmar, part of the Tell Asmar Hoard.jpeg|thumb|350px|right|男女の礼拝者(イラク博物館)]] | ||

[[画像:Oriental_Institute_Museum._God_with_ax_attacks_eagle_while_Shamash_and_Worshipper_stand_behind_(5948336437).jpeg|thumb|350px|right|ニヌルタに倒されるアンズーか。灰色の石灰岩、アッカド(前2350-2150年)、北の宮殿テル・アスマール(Tell Asmar Hoard)]] | [[画像:Oriental_Institute_Museum._God_with_ax_attacks_eagle_while_Shamash_and_Worshipper_stand_behind_(5948336437).jpeg|thumb|350px|right|ニヌルタに倒されるアンズーか。灰色の石灰岩、アッカド(前2350-2150年)、北の宮殿テル・アスマール(Tell Asmar Hoard)]] | ||

| − | '''アンズー'''('''Anzû''')は、'''ズー'''('''Zū'''、'''<sup>d</sup>Zû''')あるいは'''Imdugud'''(シュメール語:𒀭𒅎𒂂、 ''AN.IM.DUGUD[[Determinative#Cuneiform|<sup>MUŠEN</sup>]]'')としても知られている、メソポタミア神話に登場する怪物である。現在では'''アンズー'''('''Anzū''' | + | '''アンズー'''('''Anzû''')は、'''ズー'''('''Zū'''、'''<sup>d</sup>Zû''')あるいは'''Imdugud'''(シュメール語:𒀭𒅎𒂂、 ''AN.IM.DUGUD[[Determinative#Cuneiform|<sup>MUŠEN</sup>]]'')としても知られている、メソポタミア神話に登場する怪物である。現在では'''アンズー'''('''Anzū''')がより正確な呼称であるとされる。火と水を吐く巨大な鳥や、[[ライオン]]の頭を持つ[[ワシ]]の姿で表されることがある([[グリフォン]]を参照)。 |

| − | ズーは[[アプスー]] | + | ズーは[[アプスー]]の淡水と広い大地から生まれたとも、女神シリスの息子ともいわれる<ref name="Hesiod">Charles Penglase, Greek Myths and Mesopotamia: Parallels and Influence in the Homeric Hymns and Hesiod, https://books.google.com/books?id=c5gYl1px7PcC|date=4 October 2003, aylor & Francis, isbn:978-0-203-44391-0</ref><ref name="Hesiod2">Charles Penglase, Greek Myths and Mesopotamia: Parallels and Influence in the Homeric Hymns and Hesiod, https://books.google.com/books?id=c5gYl1px7PcC, 4 October 2003, Taylor & Francis, isbn:978-0-203-44391-0</ref>。 |

天の主神'''[[エンリル]]の随獣'''であり彼に仕えていたが、主神権の簒奪を目論み、その象徴である'''「天命の書版(Tablet of Destinies (mythic item))」を盗み出し'''てしまう。この話はいくつかバージョンがあり、あるバージョンでは、「天命の書板」を取り返すために神々が[[ルガルバンダ]]を送り込み、彼がズーを殺したことになっており<sup>''(要出典、2018年2月)''</sup>、また別のバージョンでは、エアと[[ベレト・イリ]]が[[ニヌルタ]]を書板の奪還に向かわせたという。また、[[アッシュールバニパル]]の讃歌では、[[マルドゥク]]がズーの討伐を命じられている。 | 天の主神'''[[エンリル]]の随獣'''であり彼に仕えていたが、主神権の簒奪を目論み、その象徴である'''「天命の書版(Tablet of Destinies (mythic item))」を盗み出し'''てしまう。この話はいくつかバージョンがあり、あるバージョンでは、「天命の書板」を取り返すために神々が[[ルガルバンダ]]を送り込み、彼がズーを殺したことになっており<sup>''(要出典、2018年2月)''</sup>、また別のバージョンでは、エアと[[ベレト・イリ]]が[[ニヌルタ]]を書板の奪還に向かわせたという。また、[[アッシュールバニパル]]の讃歌では、[[マルドゥク]]がズーの討伐を命じられている。 | ||

| − | + | ステファニー・ダリーは『メソポタミア神話(Myths from Mesopotamia)』の中で、「『アンズー叙事詩』は主に2つのバージョンで知られている。前2000年初頭の古バビロニア版では、主人公はニンギルスとされており、前1000年の『標準バビロニア』版では、最も有名なバージョンで、主人公はニヌルタである。」と記述している。しかし、以下に述べるように、他の文献にはアンズーがあまり登場しないものもある。 | |

| − | + | == 名前 == | |

| + | アンズーと呼ばれる神話上の生物は、シュメール最古の楔形文字では𒀭𒉎𒈪𒄷(''AN.IM.MI<sup>MUŠEN</sup>''、楔形記号𒄷またはMUŠENは文脈上「鳥」を表わす)と書かれていた。 古バビロニア時代のテキストでは、「𒀭𒉎𒂂𒄷 (''AN.IM.DUGUD<sup>MUŠEN</sup>'')」と表記されることが多い<ref name=alster/>。1961年、ランズバーガーはこの名前を「アンズー」と読むべきと主張し、ほとんどの研究者がこれに従った。1989年、トーキル・ヤコブセン(Thorkild Jacobsen)は、楔形文字の読み方("<sup>d</sup>IM.dugud"と表記)も有効であり、おそらくこれが本来の発音であり、「Anzu」は初期の発音変化から派生したものであると指摘している。また、「イムドゥグッ」(「重い風」の意)が「アンスク(''ansuk'')」になるなど、並列する言葉にも同様の音韻変化が起こった。このような変化は、imがanに変化し(一般的な音韻変化)、新しいnが次のdと混ざり合い、dhとして吸引され、その音がアッカド語にzやsとして借用されることで起こった<ref name=jacobsen1989>Jacobsen, T. (1989). God or Worshipper. pp. 125-130 in Holland, T.H. (ed.), ''Studies In Ancient Oriental Civilization no. 47''. The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago.</ref>。 | ||

| + | |||

| + | また、文脈上の痕跡や 楔形文字の学位記の音訳から、最古のシュメール語の名前は少なくとも時にはズーとも発音され、アンズーは主にアッカド語の名前であると主張されている。しかし、両言語には両方の読み方を示す証拠があり、接頭辞𒀭 (''AN'')がしばしば神や単に高い場所を区別するために使われたという事実によって、この問題はさらに混乱している。AN.ZUは単に「天の鷲」を意味するのかもしれない<ref name=alster>Alster, B. (1991). [https://www.jstor.org/stable/23282051 Contributions to the Sumerian lexicon]. ''Revue d'Assyriologie et d'archéologie orientale'', '''85'''(1): 1-11.</ref>。 | ||

| + | |||

| + | 楔形文字の学習用書版に基づけば、最も初期のシュメール語では少なくとも時々Zuと発音され、Anzuは主にアッカド語の名であると主張される。ただし、両方の言語でどちらの名も読み取ることができ、接頭辞𒀭( ''AN'' )が神や単に高い場所を区別するためによく使用されたため、問題はさらに複雑になっている。アンズーは単に「天国のワシ」を意味する可能性もある。 <ref name="alster" /> | ||

| + | |||

| + | == 起源と文化的変遷 == | ||

| + | トーキル・ヤコブセンは、アンズーはアブ(Abu)という神の初期の姿であり、古代人はアブを雷雨に関連する神ニヌルタ/ニンギルスと習合されたと提唱している。アブは「父なる牧場」と呼ばれ、春の雨と畑の成長を結びつけていた。ヤコブセンによれば、この神はもともと'''鷲の形をした巨大な黒い雷雲として想定され、後に雷の轟音と結びつけるために獅子の頭を持つようになった'''という。そのため、アンズーは山羊(古代中近東では雷雲と同様に山を連想させる)や葉の茂みと一緒に描かれているものもある。また、Tell Asmar Hoardから発見された、大きな目を持つ人物像の台座にアンズーの鳥が彫られていることから、アンズーとアブの関連性はさらに強くなっている。この像が実際にアンズーを崇拝する人間を表しているとする学者もいるが、シュメールの崇拝者の通常の描写とは一致せず、人間の形をした類似の神像に、より抽象的な形やその象徴を台座に刻んだものが一致していると指摘する学者もいる<ref name=jacobsen1989/>。 | ||

| + | |||

| + | トーキル・ヤコブセンは、アンズーはアブ神(Abu (god))の初期の形態であり、雷雨に関連する神である[[ニヌルタ]]/ニンギルスと習合された説を唱えた。アブは植物の神とされ、暴風雨と春に芽吹く大地のつながりを表した。ヤコブセンによれば、この神はもともと'''鷲の形をした巨大な黒い雷雲'''として想像されていたが、後に雷の轟音のイメージからライオンの頭で描かれた。アンズーは時折、山羊(古代近東では山と雷雲が関連付けられた)や葉の生い茂る枝の姿で神と共に描かれた。 | ||

| − | + | アンズーとアブ神のつながりは、テル・アスマル・ホード(Tell Asmar Hoard)で見つかった、台座にアンズー鳥が彫られた大きな目をもつ人物像の遺物によってより強調された。アンズーを人物の象徴的モチーフとして、あるいは初期の姿として用いているとも考えられ、より高次な人間に近い神の姿でアブ神を描いている可能性がある。一部の学者はこの像はアンズーを崇拝する人間を表す説を出しているが、他の学者はそれがシュメールの崇拝者の通常の描写と適合せず、むしろ同様の人型をした神の像や台座に刻まれるシンボルに近いと指摘した。 <ref name="jacobsen1989">Jacobsen, T. (1989). God or Worshipper. pp. 125-130 in Holland, T.H. (ed.), ''Studies In Ancient Oriental Civilization no. 47''. The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago.</ref> | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | グデア王の時代、ラガシュ市においては霊鳥として扱われ、ニンギルス神の象徴だったとされる。ラガシュではアンズーはしばしばライオンを足元に従えた姿で表され、アンズーがエンリル神、ライオンがニンギルス神を象徴したとも考えられている。<ref>シュメル神話の世界, 岡田明子・小林登志子, 2008, 中央公論新社, 中公新書, isbn:9784121019776, 288ページ</ref> | |

| − | + | == シュメールとアッカドの神話 == | |

| + | シュメール神話やアッカド神話では、アンズーは神々しい嵐鳥であり、南風と雷雲を擬人化したものである<ref>Jean Bottéro, L'Oriente antico. Dai sumeri alla Bibbia, https://books.google.com/books?id=hXeoYjm4tEoC&pg=PA246 , 1994, Edizioni Dedalo, isbn:978882200535-9, pages246–256</ref>。この魔物は半人半鳥で、エンリルから「運命の石版」を盗み出し、山頂に隠した。アヌは他の神々に、アンズーを恐れながらも石版の回収を命じた。ある文献ではマルドゥクがアンズーを殺したとされ、別の文献ではニヌルタ神の矢でアンズーが死んだとされている<ref>http://www.gatewaystobabylon.com/myths/texts/retellings/theftdestiny.htm, Theft of Destiny , gatewaystobabylon.com</ref>。 | ||

| − | + | また、シュメール叙事詩『ギルガメシュとエンキドゥと冥界』の前文に記された「イナンナとフルップの木」の物語<ref>http://www.piney.com/BabHulTree.html, Myth of the Huluppu Tree</ref>にもアンズーが登場する<ref>http://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/cgi-bin/etcsl.cgi?text=t.1.8.1.4&charenc=j#, The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature, 2015-03-24, https://web.archive.org/web/20120402155323/http://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/cgi-bin/etcsl.cgi?text=t.1.8.1.4&charenc=j, 2012-04-02</ref>。 | |

| − | |||

| − | + | アンズーはシュメール語の『ルガルバンダとアンズー鳥』(別名:『ルガルバンダの帰還』)に登場する。 | |

| − | == | + | == バビロニアとアッシリアの神話 == |

| − | + | 古バビロニア語版の短いものがスーサで発見された。全文はメソポタミアの神話(''Myths from Mesopotamia'')に掲載されている。ステファン・ダレイによる「''Creation, The Flood, Gilgamesh, and Others''」222ページ<ref>https://books.google.com/books?id=7ERp_y_w1nIC&q=Anzu+tablet+%22he+stole+the+ellil%22&pg=PA222, Myths from Mesopotamia: Creation, the Flood, Gilgamesh, and Others, Stephanie Dalley, 1 January 2000, Oxford University Press, isbn:9780192835895, Google Books</ref>及び「アンズー叙事詩(''The Epic of Anzû'')」(古バビロニア語版、スーザ出土、タブレットII、1-83行目、クラウス・ヴィルケによる読解)である<ref>http://www.soas.ac.uk/baplar/recordings/the-epic-of-anz-old-babylonian-version-from-susa-tablet-ii-lines-1-83-read-by-claus-wilcke.html, The Epic of Anzû, Old Babylonian version from Susa, Tablet II: BAPLAR, SOAS University of London</ref>。ニネヴェに伝わる後期アッシリア版の方が長く、『アンズー神話(''The Myth of Anzu'')』と呼ばれることが多い(全文はダレイ(Dalley), page 205)<ref>https://books.google.com/books?id=7ERp_y_w1nIC&q=Anzu+tablet+%22I+sing+of+the+superb+son%22+Ninurta&pg=PA205, Myths from Mesopotamia: Creation, the Flood, Gilgamesh, and Others, Stephanie Dalley, 1 January 2000, Oxford University Press, isbn:9780192835895, Google Books</ref>。編集したものは『アンズー神話(''The Myth of Anzu'')』に掲載されている<ref>http://www.gatewaystobabylon.com/myths/texts/ninurta/mythanzu.htm, Myth of Anzu , gatewaystobabylon.com</ref>。 | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

Also in Babylonian myth, Anzû is a deity associated with [[cosmogeny]]. Anzû is represented as stripping the father of the gods of ''umsimi'' (which is usually translated "crown" but in this case, as it was on the seat of Bel, it refers to the "ideal creative organ").<ref name="Smith">{{cite book|author=George Smith |author-link=George Smith (Assyriologist) |title=The Chaldean Account of Genesis |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=n3F4SMrYNkYC&pg=PA41 |year=1878 |publisher=[[Library of Alexandria]] |isbn=9781465527141 |pages=40–48}}</ref><ref name="Smith2">{{cite book|author=George Smith |author-link=George Smith (Assyriologist) |title=The Chaldean Account of Genesis |url=http://www.sacred-texts.com/ane/caog/caog10.htm}} "The Sin of the God Zu" at "Sacred Texts" website.</ref> Regarding this, Charles Penglase writes that "Ham is the Chaldean Anzû, and both are cursed for the same allegorically described crime," which parallels the mutilation of [[Uranus (mythology)|Uranus]] by [[Cronus]] and of [[Osiris]] by [[Set (deity)|Set]].<ref name="Hesiod" /> | Also in Babylonian myth, Anzû is a deity associated with [[cosmogeny]]. Anzû is represented as stripping the father of the gods of ''umsimi'' (which is usually translated "crown" but in this case, as it was on the seat of Bel, it refers to the "ideal creative organ").<ref name="Smith">{{cite book|author=George Smith |author-link=George Smith (Assyriologist) |title=The Chaldean Account of Genesis |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=n3F4SMrYNkYC&pg=PA41 |year=1878 |publisher=[[Library of Alexandria]] |isbn=9781465527141 |pages=40–48}}</ref><ref name="Smith2">{{cite book|author=George Smith |author-link=George Smith (Assyriologist) |title=The Chaldean Account of Genesis |url=http://www.sacred-texts.com/ane/caog/caog10.htm}} "The Sin of the God Zu" at "Sacred Texts" website.</ref> Regarding this, Charles Penglase writes that "Ham is the Chaldean Anzû, and both are cursed for the same allegorically described crime," which parallels the mutilation of [[Uranus (mythology)|Uranus]] by [[Cronus]] and of [[Osiris]] by [[Set (deity)|Set]].<ref name="Hesiod" /> | ||

| 65行目: | 68行目: | ||

*[http://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/cgi-bin/etcsl.cgi?text=t.1.8.2.2# Lugalbanda and the Anzud bird] | *[http://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/cgi-bin/etcsl.cgi?text=t.1.8.2.2# Lugalbanda and the Anzud bird] | ||

*[http://www.soas.ac.uk/baplar/recordings/the-epic-of-anz-old-babylonian-version-from-susa-tablet-ii-lines-1-83-read-by-claus-wilcke.html The Epic of Anzû, Old Babylonian version from Susa, Tablet II, lines 1-83, read by Claus Wilcke] | *[http://www.soas.ac.uk/baplar/recordings/the-epic-of-anz-old-babylonian-version-from-susa-tablet-ii-lines-1-83-read-by-claus-wilcke.html The Epic of Anzû, Old Babylonian version from Susa, Tablet II, lines 1-83, read by Claus Wilcke] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

== ズーが登場する神話 == | == ズーが登場する神話 == | ||

| 100行目: | 91行目: | ||

== 参考文献 == | == 参考文献 == | ||

| + | {{DEFAULTSORT:あんす}} | ||

[[Category:メソポタミア神話]] | [[Category:メソポタミア神話]] | ||

[[Category:グリフォン系]] | [[Category:グリフォン系]] | ||

[[Category:鷲系]] | [[Category:鷲系]] | ||

| + | [[Category:山羊]] | ||

2022年12月6日 (火) 22:33時点における最新版

アンズー(Anzû)は、ズー(Zū、dZû)あるいはImdugud(シュメール語:𒀭𒅎𒂂、 AN.IM.DUGUDMUŠEN)としても知られている、メソポタミア神話に登場する怪物である。現在ではアンズー(Anzū)がより正確な呼称であるとされる。火と水を吐く巨大な鳥や、ライオンの頭を持つワシの姿で表されることがある(グリフォンを参照)。

ズーはアプスーの淡水と広い大地から生まれたとも、女神シリスの息子ともいわれる[1][2]。

天の主神エンリルの随獣であり彼に仕えていたが、主神権の簒奪を目論み、その象徴である「天命の書版(Tablet of Destinies (mythic item))」を盗み出してしまう。この話はいくつかバージョンがあり、あるバージョンでは、「天命の書板」を取り返すために神々がルガルバンダを送り込み、彼がズーを殺したことになっており(要出典、2018年2月)、また別のバージョンでは、エアとベレト・イリがニヌルタを書板の奪還に向かわせたという。また、アッシュールバニパルの讃歌では、マルドゥクがズーの討伐を命じられている。

ステファニー・ダリーは『メソポタミア神話(Myths from Mesopotamia)』の中で、「『アンズー叙事詩』は主に2つのバージョンで知られている。前2000年初頭の古バビロニア版では、主人公はニンギルスとされており、前1000年の『標準バビロニア』版では、最も有名なバージョンで、主人公はニヌルタである。」と記述している。しかし、以下に述べるように、他の文献にはアンズーがあまり登場しないものもある。

目次

名前[編集]

アンズーと呼ばれる神話上の生物は、シュメール最古の楔形文字では𒀭𒉎𒈪𒄷(AN.IM.MIMUŠEN、楔形記号𒄷またはMUŠENは文脈上「鳥」を表わす)と書かれていた。 古バビロニア時代のテキストでは、「𒀭𒉎𒂂𒄷 (AN.IM.DUGUDMUŠEN)」と表記されることが多い[3]。1961年、ランズバーガーはこの名前を「アンズー」と読むべきと主張し、ほとんどの研究者がこれに従った。1989年、トーキル・ヤコブセン(Thorkild Jacobsen)は、楔形文字の読み方("dIM.dugud"と表記)も有効であり、おそらくこれが本来の発音であり、「Anzu」は初期の発音変化から派生したものであると指摘している。また、「イムドゥグッ」(「重い風」の意)が「アンスク(ansuk)」になるなど、並列する言葉にも同様の音韻変化が起こった。このような変化は、imがanに変化し(一般的な音韻変化)、新しいnが次のdと混ざり合い、dhとして吸引され、その音がアッカド語にzやsとして借用されることで起こった[4]。

また、文脈上の痕跡や 楔形文字の学位記の音訳から、最古のシュメール語の名前は少なくとも時にはズーとも発音され、アンズーは主にアッカド語の名前であると主張されている。しかし、両言語には両方の読み方を示す証拠があり、接頭辞𒀭 (AN)がしばしば神や単に高い場所を区別するために使われたという事実によって、この問題はさらに混乱している。AN.ZUは単に「天の鷲」を意味するのかもしれない[3]。

楔形文字の学習用書版に基づけば、最も初期のシュメール語では少なくとも時々Zuと発音され、Anzuは主にアッカド語の名であると主張される。ただし、両方の言語でどちらの名も読み取ることができ、接頭辞𒀭( AN )が神や単に高い場所を区別するためによく使用されたため、問題はさらに複雑になっている。アンズーは単に「天国のワシ」を意味する可能性もある。 [3]

起源と文化的変遷[編集]

トーキル・ヤコブセンは、アンズーはアブ(Abu)という神の初期の姿であり、古代人はアブを雷雨に関連する神ニヌルタ/ニンギルスと習合されたと提唱している。アブは「父なる牧場」と呼ばれ、春の雨と畑の成長を結びつけていた。ヤコブセンによれば、この神はもともと鷲の形をした巨大な黒い雷雲として想定され、後に雷の轟音と結びつけるために獅子の頭を持つようになったという。そのため、アンズーは山羊(古代中近東では雷雲と同様に山を連想させる)や葉の茂みと一緒に描かれているものもある。また、Tell Asmar Hoardから発見された、大きな目を持つ人物像の台座にアンズーの鳥が彫られていることから、アンズーとアブの関連性はさらに強くなっている。この像が実際にアンズーを崇拝する人間を表しているとする学者もいるが、シュメールの崇拝者の通常の描写とは一致せず、人間の形をした類似の神像に、より抽象的な形やその象徴を台座に刻んだものが一致していると指摘する学者もいる[4]。

トーキル・ヤコブセンは、アンズーはアブ神(Abu (god))の初期の形態であり、雷雨に関連する神であるニヌルタ/ニンギルスと習合された説を唱えた。アブは植物の神とされ、暴風雨と春に芽吹く大地のつながりを表した。ヤコブセンによれば、この神はもともと鷲の形をした巨大な黒い雷雲として想像されていたが、後に雷の轟音のイメージからライオンの頭で描かれた。アンズーは時折、山羊(古代近東では山と雷雲が関連付けられた)や葉の生い茂る枝の姿で神と共に描かれた。

アンズーとアブ神のつながりは、テル・アスマル・ホード(Tell Asmar Hoard)で見つかった、台座にアンズー鳥が彫られた大きな目をもつ人物像の遺物によってより強調された。アンズーを人物の象徴的モチーフとして、あるいは初期の姿として用いているとも考えられ、より高次な人間に近い神の姿でアブ神を描いている可能性がある。一部の学者はこの像はアンズーを崇拝する人間を表す説を出しているが、他の学者はそれがシュメールの崇拝者の通常の描写と適合せず、むしろ同様の人型をした神の像や台座に刻まれるシンボルに近いと指摘した。 [4]

グデア王の時代、ラガシュ市においては霊鳥として扱われ、ニンギルス神の象徴だったとされる。ラガシュではアンズーはしばしばライオンを足元に従えた姿で表され、アンズーがエンリル神、ライオンがニンギルス神を象徴したとも考えられている。[5]

シュメールとアッカドの神話[編集]

シュメール神話やアッカド神話では、アンズーは神々しい嵐鳥であり、南風と雷雲を擬人化したものである[6]。この魔物は半人半鳥で、エンリルから「運命の石版」を盗み出し、山頂に隠した。アヌは他の神々に、アンズーを恐れながらも石版の回収を命じた。ある文献ではマルドゥクがアンズーを殺したとされ、別の文献ではニヌルタ神の矢でアンズーが死んだとされている[7]。

また、シュメール叙事詩『ギルガメシュとエンキドゥと冥界』の前文に記された「イナンナとフルップの木」の物語[8]にもアンズーが登場する[9]。

アンズーはシュメール語の『ルガルバンダとアンズー鳥』(別名:『ルガルバンダの帰還』)に登場する。

バビロニアとアッシリアの神話[編集]

古バビロニア語版の短いものがスーサで発見された。全文はメソポタミアの神話(Myths from Mesopotamia)に掲載されている。ステファン・ダレイによる「Creation, The Flood, Gilgamesh, and Others」222ページ[10]及び「アンズー叙事詩(The Epic of Anzû)」(古バビロニア語版、スーザ出土、タブレットII、1-83行目、クラウス・ヴィルケによる読解)である[11]。ニネヴェに伝わる後期アッシリア版の方が長く、『アンズー神話(The Myth of Anzu)』と呼ばれることが多い(全文はダレイ(Dalley), page 205)[12]。編集したものは『アンズー神話(The Myth of Anzu)』に掲載されている[13]。

Also in Babylonian myth, Anzû is a deity associated with cosmogeny. Anzû is represented as stripping the father of the gods of umsimi (which is usually translated "crown" but in this case, as it was on the seat of Bel, it refers to the "ideal creative organ").[14][15] Regarding this, Charles Penglase writes that "Ham is the Chaldean Anzû, and both are cursed for the same allegorically described crime," which parallels the mutilation of Uranus by Cronus and of Osiris by Set.[1]

See also[編集]

- Anzu wyliei, a theropod dinosaur named for Anzû

- Asakku, similar Mesopotamian deity

- Griffin or griffon, lion-bird hybrid

- Lamassu, Assyrian deity, bull/lion-eagle-human hybrid

- Tengu, Japanese magical creature half-man half-bird

- Hybrid creatures in mythology

- List of hybrid creatures in mythology

- Tiamat

- Ziz, giant griffin-like bird in Jewish mythology

- Zeus, Greek deity of sky and thunder

- Zuism, Icelander protest against tax for religion

External links[編集]

テンプレート:Commons category テンプレート:Wikiquote

- Zu on Encyclopædia Britannica

- テンプレート:Cite book

- The Assyro-Babylonian Mythology FAQ: Anzû

- ETCSL glossary showing Zu as the verb 'to know'

- Myth of Anzu

- Ninurta's return to Nibru: a šir-gida to Ninurta and The Return of Ninurta to Nippur

- Ninurta and the Turtle and Ninurta and the Turtle, or Ninurta and Enki

- Ninurta's exploits and The Exploits of Ninurta, or Lugal-e

- Lugalbanda and the Anzud bird

- The Epic of Anzû, Old Babylonian version from Susa, Tablet II, lines 1-83, read by Claus Wilcke

ズーが登場する神話[編集]

- "Lugalbanda and the Anzud Bird"(『ルガルバンダとアンズー鳥(Lugalbanda and the Anzud Bird)』/『ルガルバンダの帰還』) - 『ルガルバンダ叙事詩』の第二部。王子を助ける霊鳥として登場する。

- "Inanna and the Huluppu Tree"(『イナンナとフルップの樹』) - 『ギルガメシュとエンキドゥと冥界』[16]の前文に記録される物語。女神イナンナのフルップ(ハルブ)の樹に巣食う迷惑者として登場。ギルガメシュによって追い払われる。

- "Lugal-e"(『ルガル神話(Lugal-e)』/『ルガル・エ』)- 悪霊アサグにつく「十一の勇士ども」の一人として登場するがニヌルタ神に殺された。

- "Ninurta and the turtle"(『ニンウルタ神と亀』/『ニンウルタ神の傲慢と処罰』) - アンズーの雛が「メ」と「天命の粘土板」をもつものとして登場。ニンウルタをアブズーに導く。

- "Angim dimma"(『アンギン神話』/『ニンウルタ神のニップル市への凱旋』) - 『ルガル神話』同様、勇士のひとりとして登場。ハルブ・ハランの木にいることになっている。

- "Anzû myth"(『アンズー鳥神話』) - 「天命の書版」を盗みニヌルタ神に退治される怪鳥として登場。

関連項目[編集]

- アサグ - 同様のメソポタミアの神

- グリフィンまたはグリフォン - ライオンと鳥の合成獣

- テンプレート:仮リンク - アッシリアの神、雄牛/ライオン-ワシ-人間の合成獣

- ティアマト

- ジズ - ユダヤの神話の巨大なグリフィンのような鳥

参考文献[編集]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Charles Penglase, Greek Myths and Mesopotamia: Parallels and Influence in the Homeric Hymns and Hesiod, https://books.google.com/books?id=c5gYl1px7PcC%7Cdate=4 October 2003, aylor & Francis, isbn:978-0-203-44391-0

- ↑ Charles Penglase, Greek Myths and Mesopotamia: Parallels and Influence in the Homeric Hymns and Hesiod, https://books.google.com/books?id=c5gYl1px7PcC, 4 October 2003, Taylor & Francis, isbn:978-0-203-44391-0

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Alster, B. (1991). Contributions to the Sumerian lexicon. Revue d'Assyriologie et d'archéologie orientale, 85(1): 1-11.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Jacobsen, T. (1989). God or Worshipper. pp. 125-130 in Holland, T.H. (ed.), Studies In Ancient Oriental Civilization no. 47. The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago.

- ↑ シュメル神話の世界, 岡田明子・小林登志子, 2008, 中央公論新社, 中公新書, isbn:9784121019776, 288ページ

- ↑ Jean Bottéro, L'Oriente antico. Dai sumeri alla Bibbia, https://books.google.com/books?id=hXeoYjm4tEoC&pg=PA246 , 1994, Edizioni Dedalo, isbn:978882200535-9, pages246–256

- ↑ http://www.gatewaystobabylon.com/myths/texts/retellings/theftdestiny.htm, Theft of Destiny , gatewaystobabylon.com

- ↑ http://www.piney.com/BabHulTree.html, Myth of the Huluppu Tree

- ↑ http://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/cgi-bin/etcsl.cgi?text=t.1.8.1.4&charenc=j#, The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature, 2015-03-24, https://web.archive.org/web/20120402155323/http://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/cgi-bin/etcsl.cgi?text=t.1.8.1.4&charenc=j, 2012-04-02

- ↑ https://books.google.com/books?id=7ERp_y_w1nIC&q=Anzu+tablet+%22he+stole+the+ellil%22&pg=PA222, Myths from Mesopotamia: Creation, the Flood, Gilgamesh, and Others, Stephanie Dalley, 1 January 2000, Oxford University Press, isbn:9780192835895, Google Books

- ↑ http://www.soas.ac.uk/baplar/recordings/the-epic-of-anz-old-babylonian-version-from-susa-tablet-ii-lines-1-83-read-by-claus-wilcke.html, The Epic of Anzû, Old Babylonian version from Susa, Tablet II: BAPLAR, SOAS University of London

- ↑ https://books.google.com/books?id=7ERp_y_w1nIC&q=Anzu+tablet+%22I+sing+of+the+superb+son%22+Ninurta&pg=PA205, Myths from Mesopotamia: Creation, the Flood, Gilgamesh, and Others, Stephanie Dalley, 1 January 2000, Oxford University Press, isbn:9780192835895, Google Books

- ↑ http://www.gatewaystobabylon.com/myths/texts/ninurta/mythanzu.htm, Myth of Anzu , gatewaystobabylon.com

- ↑ テンプレート:Cite book

- ↑ テンプレート:Cite book "The Sin of the God Zu" at "Sacred Texts" website.

- ↑ http://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/cgi-bin/etcsl.cgi?text=t.1.8.1.4&charenc=j#, The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature, 2015-03-24, https://web.archive.org/web/20120402155323/http://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/cgi-bin/etcsl.cgi?text=t.1.8.1.4&charenc=j, 2012-04-02