「フマ」の版間の差分

(→神話と伝説) |

|||

| 10行目: | 10行目: | ||

フマという鳥は、一生休むことなく、目に見えないほど高いところを飛び、地上に降り立つこともないと言われている(脚がないという伝説もある)<ref name="Nile">Nile, Green, Ostrich Eggs and Peacock Feathers: Sacred Objects as Cultural Exchange between Christianity and Islam, Al Masaq: Islam and the Medieval Mediterranean, 18, 1, <!--March-->2006, pages:27–78, doi:10.1080/09503110500222328.</ref>。 | フマという鳥は、一生休むことなく、目に見えないほど高いところを飛び、地上に降り立つこともないと言われている(脚がないという伝説もある)<ref name="Nile">Nile, Green, Ostrich Eggs and Peacock Feathers: Sacred Objects as Cultural Exchange between Christianity and Islam, Al Masaq: Islam and the Medieval Mediterranean, 18, 1, <!--March-->2006, pages:27–78, doi:10.1080/09503110500222328.</ref>。 | ||

| + | フマの神話のいくつかのバリエーションでは、この鳥は不死鳥のようであり、数百年ごとに火で自らを焼き尽くし、灰の中から新たに立ち上がる、と言われている。 | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | The Huma bird is said to have both the male and female natures in one body (reminiscent of the Chinese [[Fenghuang]]), each nature having one wing and one leg. Huma is considered to be compassionate, and a 'bird of fortune'<ref name="divan"/> since its shadow (or touch) is said to be auspicious. | |

In Sufi tradition, catching the Huma is beyond even the wildest imagination, but catching a glimpse of it or even a shadow of it is sure to make one happy for the rest of his/her life. It is also believed that Huma cannot be caught alive, and the person killing a Huma will die in forty days.<ref name="divan"/> | In Sufi tradition, catching the Huma is beyond even the wildest imagination, but catching a glimpse of it or even a shadow of it is sure to make one happy for the rest of his/her life. It is also believed that Huma cannot be caught alive, and the person killing a Huma will die in forty days.<ref name="divan"/> | ||

2022年3月25日 (金) 00:39時点における版

フマ(Huma、ペルシア語:هما、発音:Homer、アヴェスター語:Homāio)はペルシア神話上の伝説の鳥であり、[2][3]スーフィーの詩やディヴァン (詩集)で共通のモチーフとして使い続けられている。ペルシアのフェニックスと呼ばれることもあるが、実際には中国の吉兆の鳥、鳳凰と似ている部分が多い。例えば、雌雄を兼ね備えているところがある。だが、フマの場合は半分が雄で、もう半分が雌である。

様々な伝説があるが、共通しているのは、この鳥は地上に降り立つことはなく、生涯、目に見えないほど高いところを飛んで生活すると言われていることである。フマはその影の落ちかかった者すべてに恩恵を与え、ほんのわずかな間でも、その頭に乗ることのできた幸運のものは、王になることが期待できる。

この名前には多くの民間解釈があり、中でもスーフィーの師イナヤット・カーンは「Humaという言葉の中でhuは精神を表し、mahという言葉はアラビア語で水を意味する『Maʼa』 ماءに由来する」と仮定している[4]。

神話と伝説

フマという鳥は、一生休むことなく、目に見えないほど高いところを飛び、地上に降り立つこともないと言われている(脚がないという伝説もある)[5]。

フマの神話のいくつかのバリエーションでは、この鳥は不死鳥のようであり、数百年ごとに火で自らを焼き尽くし、灰の中から新たに立ち上がる、と言われている。

The Huma bird is said to have both the male and female natures in one body (reminiscent of the Chinese Fenghuang), each nature having one wing and one leg. Huma is considered to be compassionate, and a 'bird of fortune'[6] since its shadow (or touch) is said to be auspicious.

In Sufi tradition, catching the Huma is beyond even the wildest imagination, but catching a glimpse of it or even a shadow of it is sure to make one happy for the rest of his/her life. It is also believed that Huma cannot be caught alive, and the person killing a Huma will die in forty days.[6]

In Ottoman poetry, the creature is often referred to as a 'bird of paradise';[6][7] early European descriptions of the Paradisaeidae species portrayed the birds as having no wings or legs, and the birds were assumed to stay aloft their entire lives.

In Attar of Nishapur's allegorical masterpiece The Conference of the Birds, an eminent example of Sufi works in Persian literature, the Huma bird is portrayed as a pupil that refuses to undertake a journey because such an undertaking would compromise the privilege of bestowing kingship on those whom it flew over. In Iranian literature, this kingship-bestowing function of the Huma bird is identified with pre-Islamic monarchs, and stands vis-a-vis ravens, which is a metaphor for Arabs.[8] The legend appears in non-Sufi art as well.[9]

The kingship-bestowing function of the Huma bird reappear in Indian stories of the Mughal era, in which the shadow (or the alighting) of the Huma bird on a person's head or shoulder were said to bestow (or foretell) kingship. Accordingly, the feathers decorating the turbans of kings were said to be plumage of the Huma bird.[10]

Sufi teacher Inayat Khan gives the bestowed-kingship legend a spiritual dimension: "Its true meaning is that when a person's thoughts so evolve that they break all limitation, then he becomes as a king. It is the limitation of language that it can only describe the Most High as something like a king."[4]

The Huma bird symbolizes unreachable highness in Turkish folk literature.[11] Some references to the creature also appear in Sindhi literature, where – as in the diwan tradition – the creature is portrayed as bringing great fortune. In the Zafarnama of Guru Gobind Singh, a letter addressed to Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb refers to the Huma bird as a "mighty and auspicious bird".

Legacy

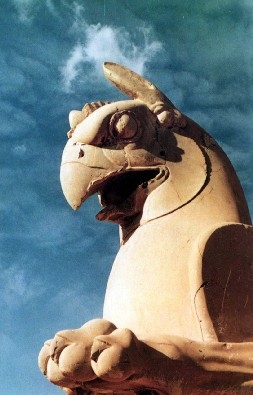

- A British Museum catalog captions a photograph of the griffin-like capitals at Persepolis with "Column capital in the form of griffins (locally known as 'homa birds')".[1]

- The Persian language acronym for "Iran National Airline" is HOMA and the airline's emblem has a stylized rendering of a Huma bird.

- The Emblem of Uzbekistan represents the Huma bird.

- Herman Melville briefly alludes to the bird in Moby-Dick. At the beginning of the chapter entitled "The Tail", the narrator speaks of "the bird that never alights."

- It provides the title of Bird's Shadow, a collection of short stories by Ivan Bunin.

- It is also referred to in the movie Days of Being Wild by Wong Kar-wai and the play "Orpheus Descending" by Tennessee Williams.テンプレート:Citation needed

- The literature series Dragonlance named Krynn's greatest hero, Huma Dragonbane, after the Huma bird.

- the asteroid 3988 Huma discovered by Eleanor F. Helin named after the Huma bird. The asteroid's name was suggested by the SGAC Name An Asteroid Campaign[12]

関連項目

参考文献

- Wikipedia:フマ(最終閲覧日:22-03-21)

- Saccone, Carlo, Humā, https://referenceworks.brillonline.com/entries/encyclopaedia-of-islam-3/huma-COM_30551?s.num=22&s.f.s2_parent=s.f.book.encyclopaedia-of-islam-3&s.start=20&s.q=Iranian , 2018

参照

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Curtis , John , Tallis , Nigel , Forgotten Empire, the World of Ancient Persia , London , British Museum Press , 2005 , isbn:978-0-7141-1157-5

- ↑ MacKenzie, D. N. ,A concise Pahlavi Dictionary, 2005, Routledge Curzon, London & New York, isbn:0-19-713559-5

- ↑ Mo'in, M., Mohammad Moin, A Persian Dictionary. Six Volumes, 1992, Amir Kabir Publications, Tehran, isb:1-56859-031-8

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 http://wahiduddin.net/mv2/II/II_8.htm , The Mysticism of Music, Sound and Word , Abstract Sound , Khan , Inayat , 1923 , wahiduddin.net

- ↑ Nile, Green, Ostrich Eggs and Peacock Feathers: Sacred Objects as Cultural Exchange between Christianity and Islam, Al Masaq: Islam and the Medieval Mediterranean, 18, 1, 2006, pages:27–78, doi:10.1080/09503110500222328.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 テンプレート:Citation

- ↑ cf. テンプレート:Citation.

- ↑ テンプレート:Citation, p. 151.

- ↑ cf. テンプレート:Citation, p. 118.

- ↑ テンプレート:Citation.

- ↑ テンプレート:Citation

- ↑ 3988 Huma (1986 LA).{{{date}}} - via {{{via}}}.